We’ve been bracing ourselves in Canada for whatever is going on with politics in the world to come here.

The rise of nationalist collectivist parties, or the shift of existing parties in that direction, has been underway on both the right and the left around the world, most noticeably for Canadians in the United States.

But not here.

It’s not that there aren’t similar sentiments in the Canadian electorate. Political strategists are chasing voters concerned about immigration, runaway global trade, and Canadian identity. But these concerns haven’t motivated enough voters for any politician to capitalize on the sort of shift seen in countries like the United States, the UK, and Poland.

The most common explanation is rising populist sentiment motivated by disaffected and left-behind voters. It seems unlikely that Canadians are almost uniquely immune to such political forces.

So why hasn’t it taken hold?

Not populism, but realignment

Stephen Davies, head of education at the Institute of Economic Affairs, thinks populist sentiment explains little about this political moment. He believes that what appears to be rising populism is really a phase in a broader political realignment. This is not a change in voter sentiments, but a shift in the main issues by which voters identify themselves with one major “side” in politics or another.

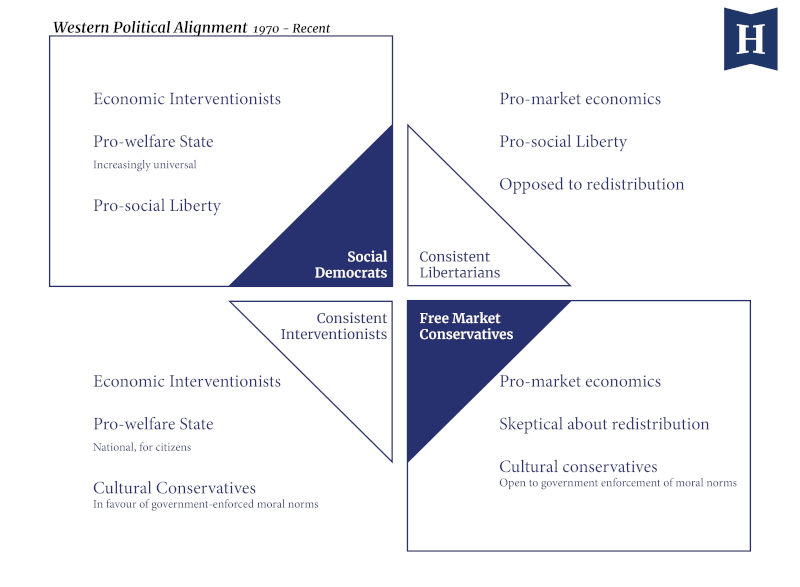

If you’ve spent much time thinking about politics, the image of political alignment since the 1970s probably looks familiar to you. The dominant contest has been between free market conservatives on the “right” and social democrats on the “left” adding to their voter base by vying for the support of median voters (who agree with both sides on some issues).

But, says Davies, this alignment has exhausted itself. The tell-tale sign is the common complaint that both sides are the same. An elite consensus emerged on old defining issues: fairly expansive social liberty and technocratic governance of relatively free-market economies.

Rising populism is a pundit’s explanation for the political reaction to this consensus. The political elite begins to cast about for positions that were previously ignored, hoping to identify voter motivations strong enough to deliver electoral victory. Since these issues were ignored in the old alignment, their advocates frame themselves as underdogs pushing back against “the elite”. Rather than a bottom-up revolution, though, Davies sees populist politics as the temporary outcome of an intra-elite battle about which positions will be contested in the future.

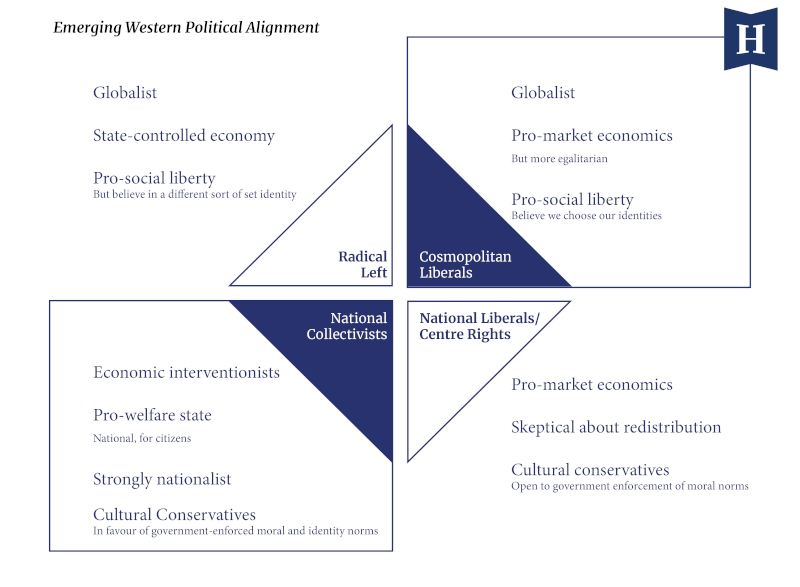

Once new defining issues are identified by the major parties, the political elite will set their messaging along those lines and previously ignored issues will have the full attention of the establishment. Once voters begin to align themselves, populist rhetoric fades away and the two parties start the decades-long journey towards a median voter consensus on the new issues.

Previously, says Davies, the primary deciding issue in politics was free markets versus interventionist economics with a secondary concern about social liberties. He believes that concern with markets will remain (though with more egalitarian market advocates), but that it will become secondary to a primary question of cosmopolitan openness or a more closed national and cultural particularism. In 2018, EKOS framed the new division between “open or ordered” in the Canadian electorate.

What makes wrapping our heads around shifting alignments tricky is that the beliefs of voters haven’t changed. They’re just facing a new calculation.

Canada has probably been stuck in political exhaustion since the Conservative Party gave up being the party for balanced budgets and against stimulus spending, but the party still sits firmly in Davies lower-right, homeless quadrant. Its ability so far to maintain this coalition is one half of the explanation for the long, stalled exhaustion of the old alignment in Canada.

The other half of the story is that the Trudeau’s Liberals, probably because of Trudeau himself, have been unwilling to let go of their commitment to economic interventionism and drift into cosmopolitan globalism. If the Liberals make that break, other issues will start to sort themselves out.

Possible shifts

Davies identifies the underlying concerns of the split: those who believe in a chosen versus a rooted identity, global metropolitan areas versus rural and declining industrial areas, and “qualified” versus “unqualified” people (as identified by educational attainment).

When asked about the national character, Canadians might ask, “Which one?” The most obvious split is between Québec and the rest of Canada. But calls for Western separation, the distinct character of the Atlantic provinces, and the growing autonomy and influence of Indigenous Peoples make our national identity inherently pluralistic. The question of “chosen individual identity versus reinforced rooted identity” seems to be playing out in Québec, but it may prove unworkable on a national scale.

National identity concerns can’t manifest so easily in Canada as opposition to trade and immigration. Before proposing a special “barbaric cultural practices hotline” in the 2015 election, Canada’s Conservative Party spent a decade quietly increasing immigration, making the case for immigration’s economic benefits, and building a multicultural voter base. Its pro-immigration history seems baked into the party, which has repeatedly rebuked overtly anti-immigration leadership candidates. It’s also difficult for Canada, with its sparse population and cold climate, to seriously consider self-sufficiency. Growing calls for managed trade and support for strategic industries seem likely, but they’re less inspiring than wholesale rejection of the global economy.

All of this may be why the divide has grabbed a toehold on the questions of urban versus rural-and-working-class norms and credentialism. Maxime Bernier can’t find success for a new political party with overtures to xenophobia as his signature policy plank, but Rob and Doug Ford can become Mayor of Toronto and Premier of Ontario.

And identity will still matter. Both the nationalist right and radical left have ideas of set identity that sit just as uneasily with the justice provided by disruptive, dynamic, open markets when identities are based in nationalism as in qualities like race and gender. This will affect how voters sort themselves into the dominant quadrants if the Canadian left embraces pro-market economics.

But it’s unclear how a contest along these lines will play out. The radically different responses to the pandemic by Donald Trump and Doug Ford illustrate that pushback against credentialism doesn’t have to mean pushback against expertise. And it’s not at all obvious that a university degree and polished urban manners are important qualities in leaders, who need good judgment much more than a degree on their wall.

And so, while the political realignment is wrapping up in some places, it’s still waiting for the starting gun here in Canada. Handled well by the political class, a realignment does not have to be as dangerous as it’s proven to be for our neighbours to the south.