Prejudice and injustice are ugly realities, based largely on a negative perception of difference, or “otherness.”

One of the the strongest tools we have to combat these forces is the power of commonality; seeing others as fellow human beings, rather than focusing on our innumerable differences. However, the growth of identity politics in mainstream discourse threatens to replace the cohesive power of commonality with a politics of resentment. This only deepens our divides, undercutting progress from a time when diversity wasn’t valued and otherness was a sure path to exclusion.

A hateful nativist sentiment was at the heart of the horrific treatment of Sikhs aboard the Komagata Maru in 1914. After a weeks-long, dangerous voyage, hundreds of people sought to make a new life for themselves in British Columbia. Instead, the ship was barred from docking. Upon their return to India, passengers faced arrest and even death.

MORE SIGNAL. LESS NOISE. THE HUB NEWSLETTER.

Similar nativism reared its head 60 years earlier when the Irish landed in North America. Fleeing a desperate famine and hoping for a better future, they were openly resented by the dominant society and subjected to abhorrent treatment, perceived to be too different, too diseased, too poor, and just plain undesirable.

Canada’s history of residential schools is another shameful example, and a much more recent one than many would like to admit. Many Indigenous people faced this traumatic reality not only during their forced attendance at these institutions but ever since then, carrying their experiences with them to this day.

There are endless examples of prejudice against numerous ethnic, cultural and racial groups in Canada’s history. The treatment of Japanese Canadians during WWII is well-known, as is the unjust Chinese Head Tax and harsh conduct toward Indigenous peoples across the Americas and beyond.

To call this racism is too narrow a term. Injustice takes many forms, based not only on race but also on various cultural and religious traits, political affiliations, sexualities and more. What links all of these shameful experiences is simply an intolerance of difference.

Otherness has been used to nefarious ends countless times, from inequality to outright genocide and everything in between. Whether it is America’s history of slavery, Hitler’s persecution of the Jews, the hostility toward Dalits in India, or China’s present-day treatment of the Uyghurs, it isn’t unique to one country or one culture, or even to one era; it continues to this day across the world.

But difference does not always lead to injustice.

In many cases, especially in modern liberal democracies, people of different backgrounds come together and recognize that they are stronger for it. The principle of tolerance makes it possible to celebrate the ways in which diversity enriches all of us.

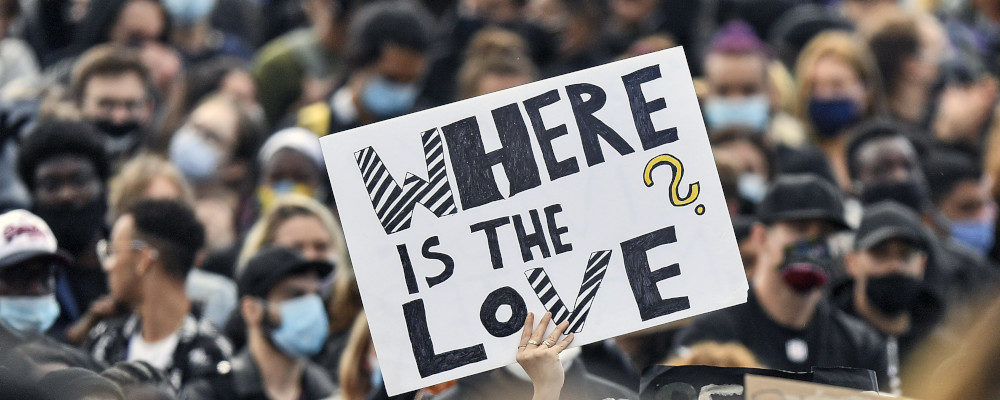

One means of encouraging this is to focus on our commonalities as human beings while rejoicing in the different ways of life made possible by a pluralistic society.

This is something that happens naturally every day. One mother identifying with another mother’s struggle to quiet a crying baby; a child bonding with another child over their mutual love of sport. Little things can bring us together as humans despite all kinds of differences that might otherwise set us apart.

It is why phrases like ‘love is love’ and ‘every child matters’ are so intuitive and effective in drawing attention to the rights of the LGBTQ community and the experiences of residential school survivors, respectively. People understand love, because they love. They know that every child matters because they how much the children in their own life matter to them.

There’s no question that diversity is a good thing and does make us stronger.

Despite its successes, this approach is increasingly being replaced by a form of identity politics that seeks both to amplify our differences and undercut the bases of our commonalities.

One example of this is Global Affairs Canada’s anti-racism materials. The materials identify statements like “we’re just one human family” as indicators of “covert white supremacy.”

It is difficult to overstate just how dangerous this thinking is. It vilifies a notion that has at its heart the very basis of common understanding and empathy. It suggests that seeing others as “like us” despite the many unique and rich cultures that could otherwise divide us, is not only wrongheaded but somehow evil.

Now, this isn’t to say our country hasn’t made mistakes and doesn’t continue to make them; we must learn about them and from them, and meaningfully address them. And this certainly isn’t to say that we ought to propose a system of assimilative policies that aims to eradicate our differences altogether. There’s no question that diversity is a good thing and does make us stronger.

But the adoption of a politics of division is bound to undo the progress we’ve achieved by magnifying our differences and exacerbating resentment.

Making matters worse, identity politics denigrates the very sentiments that bind us and threatens the idea that all of our fellow citizens, despite our differences, are bound together as (dare I say it?) one human family.

Ultimately, it can only lead to the revival of the same old intolerance that we have tried so hard to leave behind.

It is a recipe for strife and we’ll all be worse for it.