As a federal election gets underway rest assured that the most consequential policy issue facing the country will not be a subject of polite political debate.

This singular topic isn’t being swept under the carpet and away from legitimate political discussion because it’s a divisive cultural or linguistic issue. Quite the contrary. The near total silence of the punditocracy and political class on this key issue is deeply ingrained behavior; the culmination of decades of assumptions about one critical national institution and its supposed indefinite license to function beyond “politics” for the betterment of Canadians.

MORE SIGNAL. LESS NOISE. THE HUB NEWSLETTER.

The debate we urgently need to have but won’t during the coming campaign is the profound effect of our central bank and its monetary policy on our economy and politics.

To state the obvious, the Bank of Canada’s impact on our day-to-day lives over the last eighteen months has gone from moderate to extreme. As interest rates were manipulated to record lows by the central bank, already frothy pre-pandemic home prices have soared twenty five percent, the stock market is hitting dramatic, all time highs and economic inequality is exploding.

As important as these immediate and oversized effects of central bank interventions are for all of us, they are but symptoms of a more profound, high-stakes reworking of our economy by a single institution whose policies consistently elude sustained public scrutiny and political debate.

Take the basic rate of interest. The exclusive purview of the BoC, rate setting performs the essential function of connecting present and future value. To state the obvious, money in the future is less desirable than money in the present as the latter is inherently risky. Will the company I am investing in still be business in five years? Can I get repaid a loan I am about to make? Interest rates allow everyone to assess risk.

Government rates are especially important by enabling market participants to compare the return on a private investment to the proscribed interest for highly secure government bonds. These calculations, happening millions of times a day, are the longstanding genius of modern markets and the essence of their ability to allocate society’s resources efficiently.

Enter first the Great Financial Crisis and then COVID and we now find ourselves in a world of central bank manufactured interest rates. Across the board, from federal to provincial to corporate debt, the Bank of Canada is engineering rates lower by racking up, a latest count, almost half a trillion dollars of debt instruments on its balance sheet. The long term, deleterious effects of the continued artificial suppression of interest rates cannot be understated.

The signal markets need to avoid malinvestment (e.g. interest rates that reflect actual market participants’ assessment of credit risk and return on capital) has been lost in the noise of unprecedented central bank intervention. Every month the economy endures the artificial suppression of rates, more of your savings are allocated to unproductive, if not failed, enterprises, that otherwise would have been shuttered in an efficient market.

Politicians, through their profligacy, are de facto setting interest rate policy.

This clearing function of markets and the critical role played by non (or less) engineered interest rates is essential to boosting productivity, new business formation, economic growth and rising living standards. Just look at Japan and Europe in terms of the profound costs of aggressive central bank rate manipulation; a generation and more of sclerotic economic growth and critical national industries plagued by one in five “zombie” companies able only to service the interest on their debts, not repay the loan principal.

Current monetary policy, with almost no debate, is eroding the key reason for why we tolerate the less than desirable externalities of free(er) markets from inequality to ownership concentration to state capture. We have long suffered these and other “tragedies of the commons” because markets work miracles in terms of our single greatest economic challenge: the efficient allocation of capital across society. Nothing has, or will ever, do it better.

Yet thanks to unquestioning support for massive, unceasing central bank repression of interest rates we can now enjoy a capitalism producing negative externalities and inefficient markets.

Barring some exogenous shock that challenges current monetary orthodoxy and central bank supremacy, Canada is slow walking into a twilight era of managed capitalism and all the economic underperformance this will entail.

Alas, no party platform or national leader has much of anything to say about the country’s pernicious, now decade-long acceleration towards a central bank coordinated economy and a low-growth economic order that will negatively impact everything from the social safety net to healthcare spending to our ability to fight climate change.

Much of the quiescence of our political class towards monetary policy lies with the much-vaunted concept of central bank independence; a hallmark of post-Depression era economics that helped usher in decades of economic growth. Its key insight was that economies run far better when self-interested politicians aren’t determining the rate of inflation or the relative value of a currency (look at Turkey today). Leave these important decisions to an impartial referee outside politics who is tasked with managing currency, inflation and employment.

Flash forward to the decade of excessive monetary policy that followed the global financial crisis followed by extreme government suppression of interest rates during COVID, and it’s now a valid question whether central banks are still independent.

This we know: central bank-enabled indebtedness, fueled by ultra-low interest rates and unprecedented bond purchases, has exploded in last eighteen months.

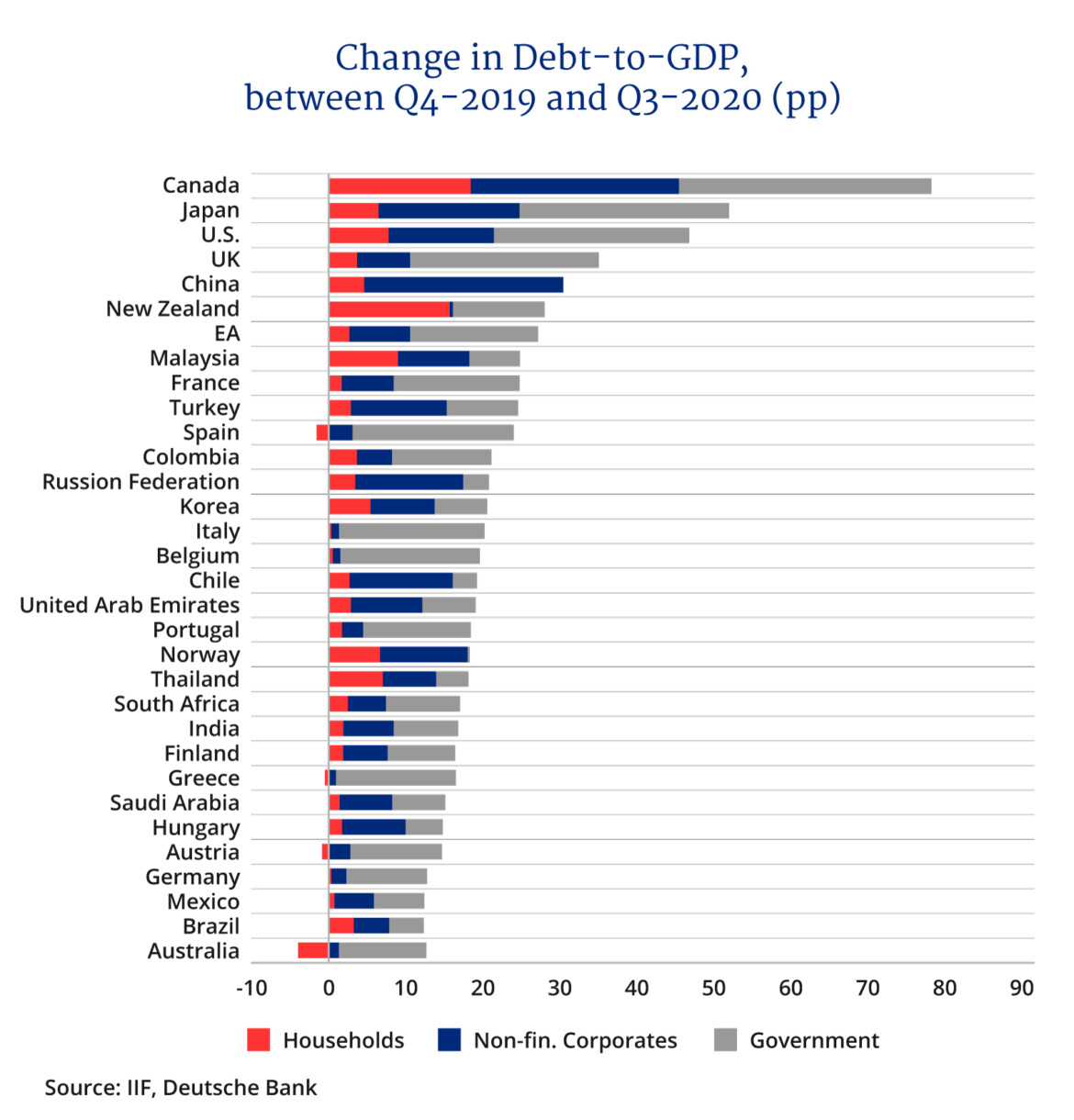

In Canada, debt-to-GDP (government, corporate and personal) increased by an astonishing 80 percent in first year of pandemic (7); a record among all advanced economies. It is this colossal debt overhang that prompts the Bank of Canada’s Tiff Macklem to make statements like “Our message to Canadians is that interest rates are very low and they’re going to be there for a long time.”

Translation: there will be no normalization of ultra-low interest rates. They will be suppressed indefinitely through large-scale bond purchases to allow our high debt, “zombified” economy to avoid a credit reckoning of truly epic proportions.

Our political class has caught onto this reality and herein lies the real reason for their cross-partisan and conspicuous silence on the risks of the country’s monetary extremism. There is no exit for the central bank from its cheap money policy and ipso facto there is no fiscal check on government policy.

Extend CRB by a month for $3 billion — why rush? Bail in Newfoundland’s Muskrat Dam to the tune of $2 billion — it’s what federalism demands. $8 billion to settle First Nations drinking water court case — we lost, we paid. $2.5 billion for seniors who saw no decline in OAS/GIS — hey don’t they deserve something too? And on, and on and on….

All these expenditures will be paid for by issuing new debt that the central bank will print money to purchase or risk rates rising not only for the now heavily indebted federal and provincial governments but debt engrossed corporations and consumers (fully one third of Canadians are financially insolvent). A “long time” to quote Tiff Macklem is just that, an indefinite period.

If this doesn’t sound to you much like the behavior of an “independent” institution, you are not alone. The proverbial bank vault is wide open and the very thing that independent central banking was supposed to prevent is tragically coming to pass: politicians, through their profligacy, are de facto setting interest rate policy and the central bank, trapped by the tsunami of debt its has enabled, can’t do anything about it.

Eventually, Canada’s experiment, as a small country, with a path dependent and radical monetary policy will end badly. To state the obvious, the Canadian dollar doesn’t enjoy reserve currency status. No one needs anything we have that they can’t purchase elsewhere in USD, yen or euro. This most certainly includes government debt, which the world will be awash in for years to come, that we will continue to sell at artificially low rates, in a currency backed by an economy two thirds the size of California with a record of poor productivity growth.

Sooner possibly than later, we will experience either a significant currency deprecation relative to our peer nations (thereby importing inflation) or suffer one of the most painful debt workouts in our history (including the painful popping of the housing bubble) or a malicious combination of both that is too awful to contemplate.

None of these policy decisions — choices that could have a profound effect on our individual quality of life in the years to come — will be debated during the election with any rigor or substance. Instead our political leaders will close their eyes, link hands and hope that central bank’s magical money tree will continue to shower the country in financial largess for as long as it takes for them to get (re)elected.

Oh Canada indeed.