Bonuses given by governments to encourage people to get vaccinated against COVID-19 are having no effect and could even be making some people less likely to get the shot, according to a new study released this week by the National Bureau of Economic Research in the United States.

Since the shots became widely available in North America, governments at all levels have been throwing money and quirky prizes at people to increase the rate of vaccinations. The incentives have been especially prevalent in the United States, where the number of people who have received a single shot hovers around 66 percent, compared to nearly 80 percent in Canada.

Another study released earlier this month found no statistically significant increase in people getting vaccinated after a weekly $1 million lottery draw was announced to much fanfare in Ohio.

Even the raw numbers suggested early on that the results of these incentives would be underwhelming. Despite a small uptick in vaccinations after incentives were announced, it usually tapered off quickly in most jurisdictions.

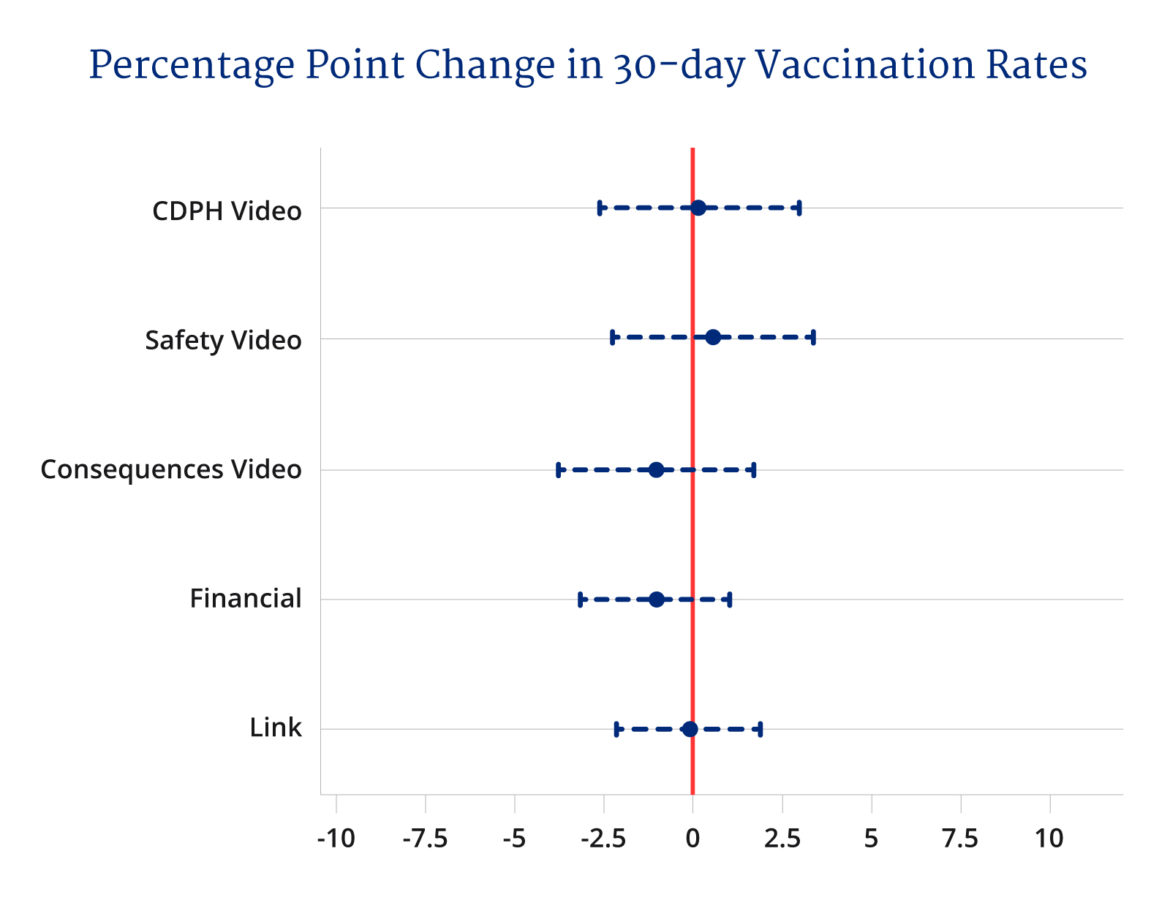

In the NBER study, researchers tried to drill down on the particular effects of a few different methods for encouraging people to vaccinated. The researchers randomly assigned members of a particular health plan either a cash bonus, one of a few different health messages or a simplified vaccine appointment scheduler. After 30 days, the researchers then followed-up with each study participant to find out if they got vaccinated.

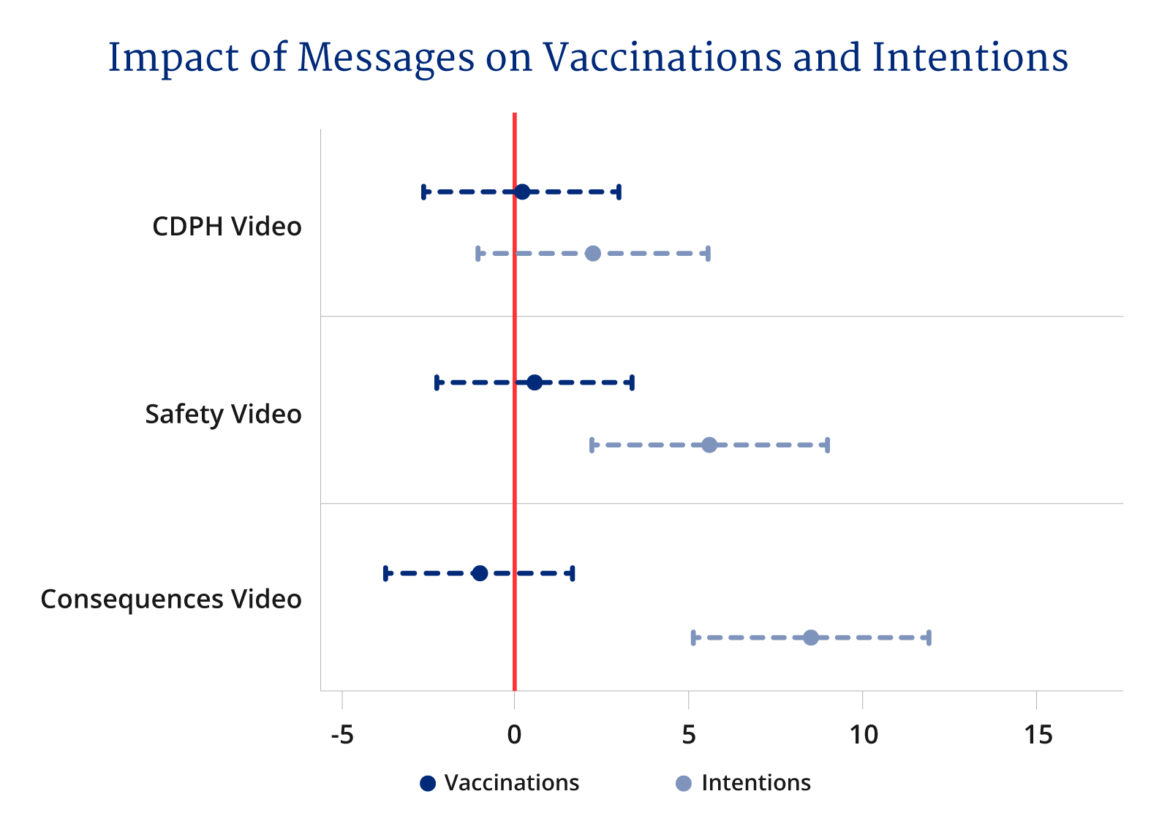

While the financial incentives showed no positive effect, and even reduced the likelihood of vaccination among Trump supporters in the study, a safety-focused health video caused a small boost in the vaccination rate.

A similar health video focusing on the negative consequences of not getting vaccinated caused the biggest reduction in the chances that a study participant would get a shot.

Although a few previous studies noticed a significant increase in people’s intention to get vaccinated after cash prizes were announced, the NBER researchers found that these intentions rarely turned into action. The video that focused on the negative consequences of not getting vaccinated actually caused the biggest boost in people’s intention to get vaccinated, but ultimately made them less likely to get the shot.

The researchers noted a few limitations of the study, most importantly that the participants of the study were recruited from a single health plan and so there’s no guarantee that these results will generalize beyond that group.

In Canada, where vaccine uptake has generally been strong, the federal government has focused on a few highly-targeted programs at specific groups, rather than splashy cash prizes. In Alberta, where the vaccine rate has lagged behind the rest of the country, the government unveiled a lottery with three $1 million cash prizes to be drawn throughout the summer.

In the U.S., states announced a bevy of prizes, lotteries and other inducements to get people vaccinated, with tens of millions of dollars going out the door. Private sector employers have also rolled out bonuses to encourage workers to get the shot.