In a forthcoming episode of The Hub’s podcast, Hub Dialogues, slated for February 15, I ask Brian Dijkema, the Cardus Institute’s vice president of external affairs, about what he thinks trade unions need to do to remain relevant in the modern economy. His answer is as follows:

Our [labour relations] system and the structure in which labour and capital are set up in North America was built in hell. We have a system that was adopted in 1945 [and] adapted from the Wagner Act in the United States, which is passed in the 1930s. The North American labour environment is therefore one where you have the Americans adopting it in the midst of the Great Depression and the Canadians adopting it at the end of the Second World War. So I say it’s been basically built in hell.

One of its key assumptions is that there’s an antagonistic relationship between labour and capital. But that assumption is disputable, and I just say is not actually true. When you look at it, there always going to be differences between labour and capital. Their interests are not always perfectly aligned. But I think we in North America, I think trade unions themselves, live too much into that adversarial relationship. And that, like any other time when you have any polarized debate, it spins the two off against each other, and that actually breeds a lot of suspicion and distrust. One consequence is that in North America you can see that a lot of people don’t actually care for unions. But I don’t think that’s necessary. There are many other examples around the world where there’s a more collaborative approach built into the legal regime for labour relations.

It’s a must-read analysis from someone with deep roots in the Canadian trade union movement. He’s in effect saying that our model for labour relations was conceived in a particular moment and context and hasn’t kept up with structural changes in our economy and society. The old industrial model has since been reshaped by the shift from a goods-producing economy to a service-based economy. Yet North American trade unions still haven’t reconceptualized their mission, purpose, and operations accordingly.

The result is an ongoing adversarialism that seems out of step with the rise of new, unconventional forms of work including so-called “gig work” which spans from an Uber driver to me. Jamming both of us into the same, old model of labour relations is self-evidently dumb.

As Dijkema has written elsewhere, these evolving labour market developments require a “revival of solidarity” which he defines as a form of labour subsidiarity that eschews national politics for a community-centred model of unionism that prioritizes workers and their families. The idea is that unions ought to come to see themselves as civil society institutions rather than hyper-political organizations uniformly dedicated to various left-wing causes.

The risk of course is that otherwise trade unions will continue to fade into obscurity due to what he characterizes as a mix of “continual decline in membership, inability to attract the next generation, growing distrust, and [other] structural challenges.” This can hardly be overstated: labour unions face something approaching an existential crisis.

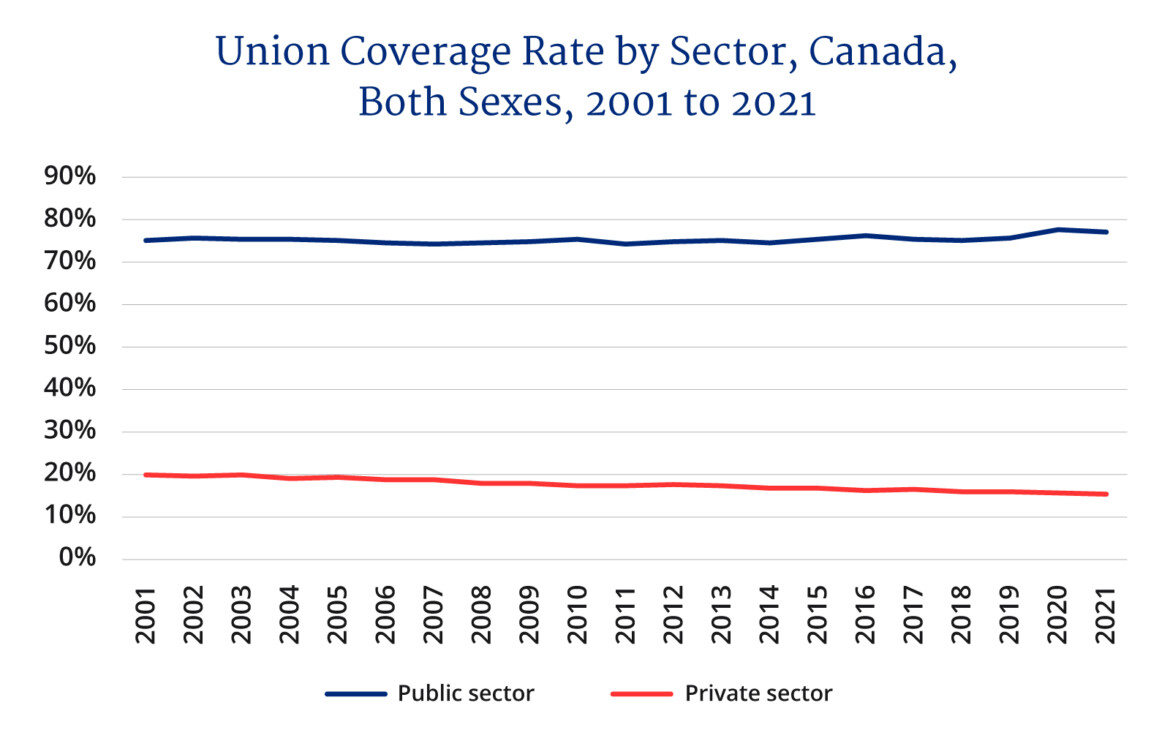

Readers will likely know that union density, which measures the share of the workforce represented by a union, has fallen precipitously in the past several decades. The total unionization rate has dropped from 37.6 percent in 1981 to 30.9 percent in 2021. But this number is inflated by the ubiquity of unionization in the public sector. Consider, for instance, that the country’s private-sector unionization rate has fallen from 19.9 percent to just 15.3 percent between 2001 and 2021 alone.

The key question, then, is whether unions can move beyond the old model of labour organizing and adapt to these new developments?

What’s interesting is a few days after recording the podcast episode we had an announcement from Uber and the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Canada on a new, innovative partnership that would enable Uber workers to avail themselves of the union’s services and supports in various aspects of their interactions with the platform-based company.

This is a big deal. Just think there are roughly 100,000 Uber drivers and delivery people in Canada. Although these workers won’t be members of the unions per se, they’re now part of its broad orbit and come with a combination of new resources and responsibilities. It easily amounts to one of the biggest cases of union renewal in Canada in recent years. It’s no accident, for instance, that NDP MP Charlie Angus described the arrangement as “a strong step forward.”

As for the workers, while the agreement doesn’t give them collective bargaining rights, it does extend a new range of workplace protections including third-party representation in dispute resolution as well as Uber-UFCW collaboration on advocacy for broader policy reform with respect to gig work. This should help to bring greater balance to the relationship between Uber and the drivers and delivery people who use the platform.

It’s difficult to know where this agreement goes from here. The joint press release from Uber and the UFCW has the latter’s Canadian president referring to the agreement as “a start in advancing a better future for app-based workers.” It’s possible of course that the UFCW sees it as an entry point to actually organize among platform-based workers.

But it may be that the Uber/UFCW arrangement creates a contemporary model of labour relations in which workers are able to leverage aspects of union representation and supports in new and different ways. Some may involve traditional union dues. Others may rely on forms of so-called “company-union” deals. Some might entail conventional collective bargaining. Others might instead emphasize other auxiliary services and supports such as skills training or portable benefits. This type of trade union pluralism would be a positive development for workers and for the unions themselves.

The key point though is that if unions are to have a future in the modern economy outside of the public sector, they’re going to need to go through a process of rebirth. The good news is that the Uber/UFCW agreement could be the basis for such a new and different future—one built in a renewed spirit of solidarity and pragmatism rather than in hell.