Don’t ask me what I’ll do when I retire because I never will. There will always be a new wine to try, even if all that’s changed is the vintage. There will always be a new wine region to find out about, even if it’s just a corner carved out of an old one. And there will always be something about wine to write, even if it’s just in the latest volume of my notebook and journal. There is no shortage in the supply of things to find out about wine. It is an ever-expanding universe that even the most learned expert can never hope to fully master.

There is also no prism of human discipline through which the wine world cannot be viewed. It encompasses everything from chemistry, to geology, to economics, to politics and history, and those are just some of the more obvious ones. The question then becomes, in light of this embarrassment of wine-factual riches, what’s important to know?

I have been thinking philosophically about wine knowledge lately because of two recent events. The first was the rewarding April trip to Loire Valley I wrote about in my last Hub column.1Loire Valley wines to watch for this spring https://thehub.ca/2022-05-06/loire-valley-wines-to-watch-for-this-spring/ It engendered the second because it reminded me of France’s great culinary heritage and culture, of which wine is just a small, if very important, part. That sent me back to my bookshelves where I pulled out my long time neglected 1961 English language edition of the Larousse Gastronomique.2“Since its first publication in 1938, Larousse Gastronomique has been an unparalleled resource. In one volume, it presents the history of foods, eating, and restaurants; cooking terms; techniques from elementary to advanced; a review of basic ingredients with advice on recognizing, buying, storing, and using them; biographies of important culinary figures; and recommendations for cooking nearly everything.” https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/815612.Larousse_Gastronomique

The Larousse Gastronomique was first published in Paris in 1938 under the authorship of Prosper Montagné, who was then France’s most famous chef. It is an encyclopedia of mostly French ingredients and culinary techniques. It was surfed by our forebear foodies the way we do the internet. Glancing through it for fun, I decided to look up the entry for “Wine”.

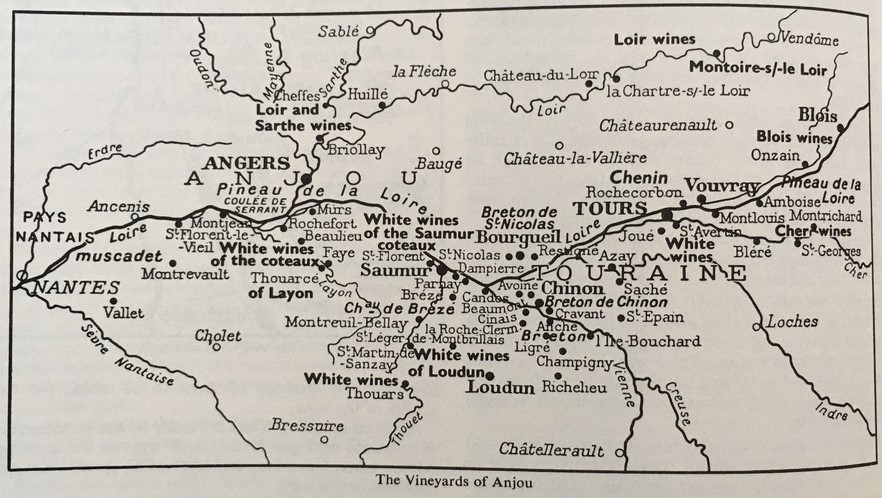

The first thing I saw pulled me back to the trip: a map of the Loire Valley.3“The Loire Valley (French: Val de Loire, pronounced [val də lwaʁ]; Breton: Traoñ al Liger), spanning 280 kilometres (170 mi), is a valley located in the middle stretch of the Loire river in central France, in both the administrative regions Pays de la Loire and Centre-Val de Loire. The area of the Loire Valley comprises about 800 square kilometres (310 sq mi). It is referred to as the Cradle of the French and the Garden of France due to the abundance of vineyards, fruit orchards (such as cherries), and artichoke, and asparagus fields, which line the banks of the river.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loire_Valley Except it wasn’t labelled that. It was called “The Vineyards of Anjou” and so enjoyed an alphabetical prominence of place. The 1961 Larousse has a few colour plates of grand dishes in its middle, but the majority of its illustrations (when an entry is important enough to have one) are in black and white. The map of the western Loire Valley, stretching from just before Vouvray to the confluence of the Sèvre at Nantes, was just a simple line drawing with typeset labels.

The map’s simplicity was arresting and helpful. Modern maps, like the ones that come up on a quick Google search, will often use a panoply of colours and shadings to show different regions and sub-regions. They will also often cram as many labeled features as they can in an array of different fonts down to the locations of famous vineyards and wineries. With its fine black lines, the older map made clear something that I had only dimly dawned on me on the trip. The Loire is more than the big river valley; it’s a system of tributaries that join it and affect the climate of each small region distinctly.

There’s nothing wrong with the modern maps. For one thing, they’re good for finding out where wine is made if you wanted to visit, and once you identify what you’re looking for, provide as much information as possible. The older map, for instance, shows no roads. Without wine tourism, why would it? They also tend to be on a larger scale, showing a smaller geographic area, as the number of wine appellations grows and divides into sub-regions or “villages”. The 1961 Larousse, by contrast, only shows the top five French regions, including Alsace, Bordeaux, Burgundy, and Champagne on a relatively small, bird’s eye scale. Again, why would it? Since little fine wine was produced elsewhere and the number of producers, including representative “négotiants”, was small.

This is not to say the old Larousse was not full of information. The wine entry spans more than a dozen pages and includes illustrations, photographs, and tables, as well as the maps. It’s just that a lot of the information seems kind of odd by modern sensibilities because it’s quite technical. Contemporary wine reference books also include lots of information that’s technical, about everything from yeast strains to different bottle sizes. But the Larousse gets really into detail into things like what chemicals to use to create certain tastes in wine. I wonder if the book was used as a how-to in some French cellars, the way the rest of the book might be used in the kitchens of the Republic’s chefs.

In terms of advice to wine consumers, the old book provides a thoroughly prescriptive chart called: “TABLE SHOWING THE SERVING OF WINES”. It suggests pairing by course from soup to nuts, as it were. With the soup, one could choose from Madeira, Marsala, Port, Sherry, or Zucco. I had to look it up, and it turns out that Zucco was (is?) a sweet wine made in Sicily from just the Cattarato grape around a town of the same name near what is now the Palermo airport. Things get a lot more French after that, and the service of the “First Main Course” is a selection of Bordeaux Crus, while “With The Roast” is all red Burgundy. This seems to confirm the accounts I have read that until relatively recently, Bordeaux was considered lighter and more finessed than Burgundy. At some point their relative positions switched.

The next table is much bigger, taking up an entire page of the book, and it’s much more directed toward French wine chauvinism. The “TABLE RELATING WINES TO FOOD” flips the premise and suggests foods to pair with particular French wines. I noted with interest and pleasure that the 1961 Larousse suggests pairing Montrachet and Muscadet with foie gras and leaves Sauternes at dessert, as I prefer. The final table is a vintage chart for various French wine regions, ranking the years going back to 1917 on a four-star system. Was this the inspiration for Robert Parker’s 100-point scale system, invented 20 years later?4“The 100-point scale for wine rating is common in North America and is analogous to school grades: Anything over 90 is excellent; 80 to 89 is above average, and so on. This system was made ubiquitous by American wine critic Robert Parker — he even trademarked the term “Parker Points.” This system is used by The Wine Advocate, the publication that Parker founded (and from which he officially retired in 2019, though the magazine continues to publish wine scores by its panel of critics).” https://edifyedmonton.com/food/drinks/the-basics-of-the-100-point-scale-for-wine-ratings/#:~:text=A%20wine%20that’s%20rated%2090,complex%20flavours%20and%20balanced%20structure.&text=The%20100%2Dpoint%20scale%20for%20wine%20rating%20is%20common%20in,above%20average%2C%20and%20so%20on.

The French have a saying that goes something like “A person must be of her time.” I have always taken it as both good advice and a statement of fact. There are all kinds of modern wine writing, conveying all sorts of varying information. Still most I read, and what I mostly write, includes some idea of what the wine itself tastes like and a description of the place it comes from and the people who made it. There is very little of this in the older book, and it makes me wonder if there will be in the wine books, or websites, or whatever form writing takes 50 or 60 years from now. I hope so.