The COVID-19 pandemic saw a surge in Canadian federal government spending the likes not seen since World War II.1Budget reaction: We can’t have big government without paying for it https://thehub.ca/2022-04-08/budget-reaction-we-cant-have-big-government-without-paying-for-it/ Expenditure changes in a federation affect not only the government in question but also the other levels of government in terms of spending balance. Indeed, expenditure shares by tier of government provide a measure of the extent to which a federation is more centralized or decentralized, and over time that balance can change.

While Canada’s constitution lays out the expenditure responsibilities and revenue tools of the federal and provincial governments—with the municipalities a creature of the provinces—over time there has been a give and take of spending responsibilities that reflect the policy decisions, politics, and demands of the era. What shapes have those trends taken over the years?

In constructing measures since Confederation, a number of data sources are needed. For the period from 1870 to 1926, annual government expenditure numbers from Mac Urquhart’s GDP estimates only pertain to goods and services spending with no separate transfer estimates. However, federal transfers to the provinces during this period are readily available and averaged about 15 percent of federal spending. They are used to estimate federal spending net of transfers from 1870 to 1926. Provincial spending for this period, unfortunately, includes transfers to municipalities, but they were not particularly well developed prior to the 1920s, accounting for only about one percent of provincial spending even by the 1930s.

As well, public education is part of government spending in Urquhart’s numbers as a separate category. The estimates here divide them across local and provincial governments in a 70/30 split based on the evidence available from Historical Statistics of Canada. There is a gap from 1927 to 1932, and then estimates only for the years 1933, 1937, 1939, 1941, and 1943 from Historical Statistics of Canada2Historical Statistics of Canada https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-516-x/11-516-x1983001-eng.htm (SeriesH161- 175; H176-187 and H188-196). For these numbers, federal transfers to other governments are accorded to the provinces and provincial transfers to other governments are accorded to local government spending.

The period from 1945 to 1969 is again annual data from Historical Statistics of Canada (as per the series listed above) and net of transfers to lower-tier governments. For the period since 1970, the years 1970 to 1990 are from the 1995 Fiscal Reference Tables while 1991 to 2020 are taken from the 2021 Fiscal Reference Tables. Again, federal transfers to other governments are accorded to the provinces and provincial transfers to other governments are accorded to local government spending.

So, what are the results?

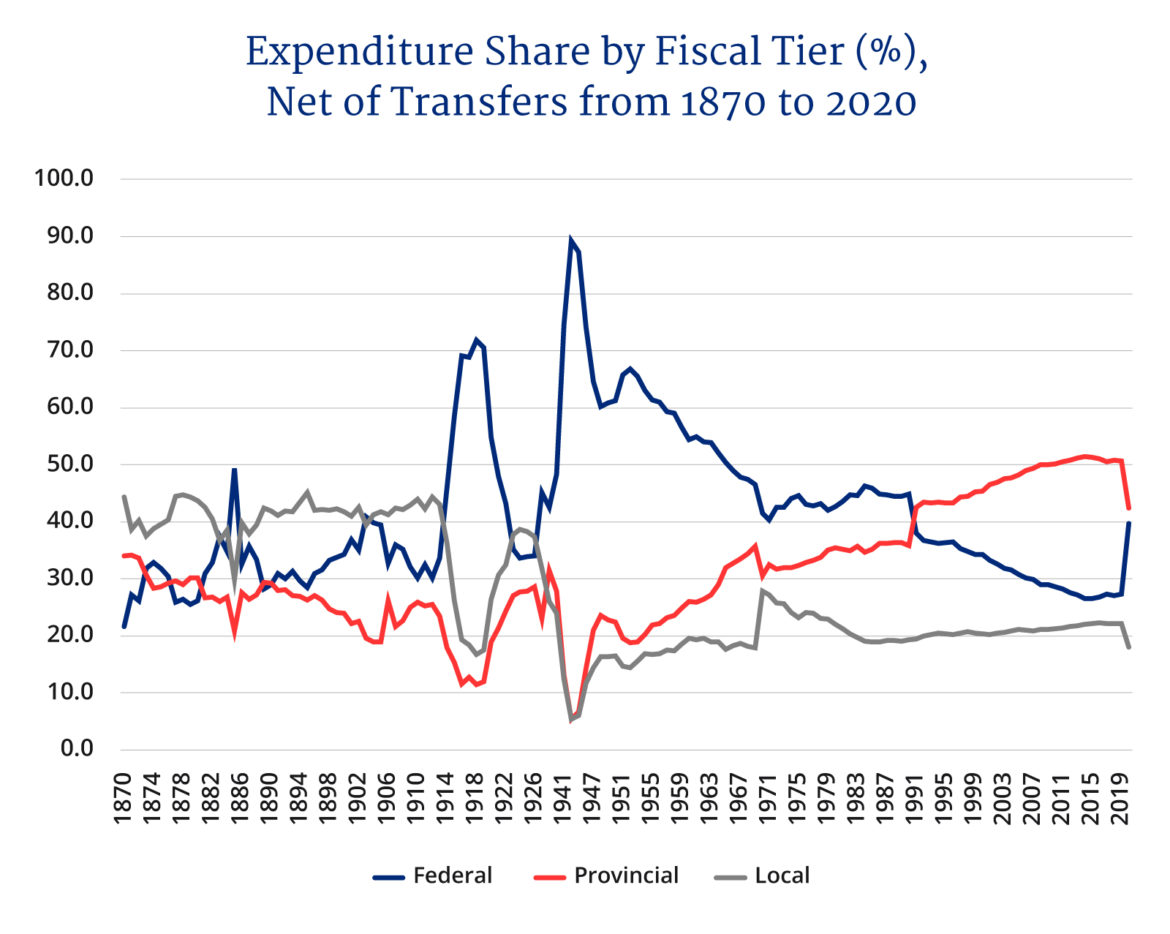

As the accompanying figure shows, until World War I the federal share of total government spending rose gradually with a spike during the CPR railway building period. The federal share averaged 33 percent while the provincial share averaged 26 percent and the municipalities averaged 41 percent. For nearly the first fifty years of Confederation, Canada was actually quite decentralized as the dominant fiscal tier in Canada was actually municipalities. The start of the First World War and the demands of the war effort sparked a shift in fiscal balances that saw the federal share soar to 70 percent while municipalities dropped to about 20 percent and the provinces 10 percent.

The 1920s saw a rebound in provincial and municipal shares with municipalities reaching just under 40 percent and the provinces under 30 percent while the federal government declined to about 35 percent. The new revenue tools that Ottawa acquired during the World War I era—income taxes and the federal sales tax—ultimately resulted in an expansion of its role that was given further impetus by the Great Depression and then World War II.3Canadian Sales Tax Reform http://taxexecutive.org/canadian-sales-tax-reform/#:~:text=It%20all%20started%20as%20a,transactions%20other%20than%20retail%20sales.

The period from 1914 to 1945 sees the spikes in the federal shares as a result of the war with a return to the prewar balance during the 1920s and early 1930s. The period since 1945 sees a steady decline in the federal share from a peak of about 90 percent in 1943 to reach 27 percent by 2016. Provincial and local shares in 1943 were at about 5 percent each and grew with the local share, levelling off at about 20 percent and reaching 22 percent by 2016 while the provinces grew steadily with their share in 2016 reaching about 50 percent.

There are some periods of abrupt shifts —the late 1950s and 1960s—which coincide with transfer regime changes such as the onset of formal federal transfer arrangements like Equalization4What is Equalization? https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/federal-transfers/equalization.html and Medicare.5Canada’s Health Care System https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/health-care-system/canada.html Then the federal fiscal crisis of the 1990s sees a period of steady decline in the federal spending share until the pandemic year of 2020 when there is a jump to 40 percent.

There are several stories here as the balance of the federation turns. The balance between Ottawa and the provincial-local sector in the early years of Confederation was a 40/60 split. After the mid-twentieth century, the federal share declined from a wartime peak of 90 percent. By 2019 it was a 30/70 split. The larger federal role earlier in the immediate post-World War II era was an aberration brought about by the demands of global war.

However, the more interesting change is the reversal of provincial and local government expenditure shares over time. While local governments were more important in terms of their spending shares before WWI, their role diminished significantly after WWII. Much of this change was of course the expansion of health, education, and social welfare functions at the provincial levels.

Essentially, Canada has been simultaneously decentralizing and centralizing since the 1970s—depending on your vantage point. The share of provincial spending rose relative to the federal government—a decentralization—and also relative to municipalities—a centralization. So, Canada became more decentralized at the federal-provincial level and more centralized at the provincial-local level.

The pandemic appears to have delivered an abrupt change to these trends with the federal share rising and both the provincial and municipal shares dropping.

The more interesting question is what happens next. Do the numbers for 2020 herald a return to the approximate 40/60 split of the pre-World War I era or is it temporary? Given the planned expansion of the federal fiscal footprint through new spending aside from transfers outlined in the most recent federal budget, the post-COVID era could mark a new expansive phase of the federal role. The federal government to date has been resisting calls for increased social and health transfers to the provinces, preferring to go its own way on child care and dental care.

Canada’s constitution outlines federal and provincial powers; however, spending balances are not anchored on blocks of granite but evolve in response to the dynamic between the tiers. Where the balance of the federation settles in the wake of the pandemic will depend on the health of federal finances, how willing it is to assert the federal spending power with respect to the provinces, and the quality of provincial leadership in pushing back.