Between April 2020 and December 2021, the Bank of Canada added $360 billion of bonds to its balance sheet as part of its quantitative easing (QE) program. It mostly bought Canadian government bonds, but also provincial bonds and mortgage-backed securities.

Outside of the first few months of the crisis, when it helped prevent Canadian financial markets from seizing up, QE probably had a negligible effect on the Canadian economy. Swapping one type of government debt (government bonds) for another (bank reserves) did not cause the current surge in inflation.

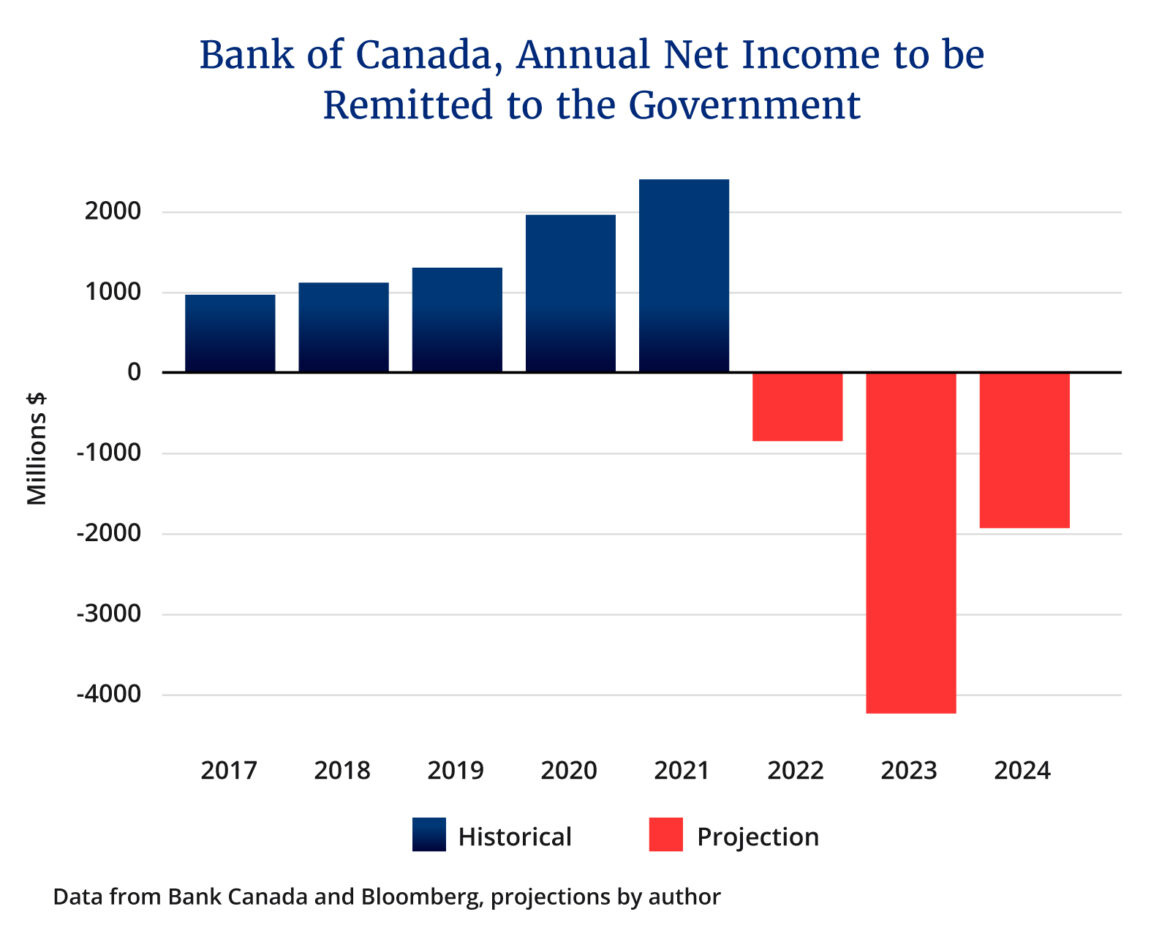

But it did have a major impact on the state of government finances going forward. We will have a preview of this “QE bomb” on public finances when the Bank reveals it generated a negative net income in 2022 and Ottawa is forced to bail it out. The Bank should be transparent about the upcoming shortfall and add safeguards around the use of quantitative easing policies going forward.

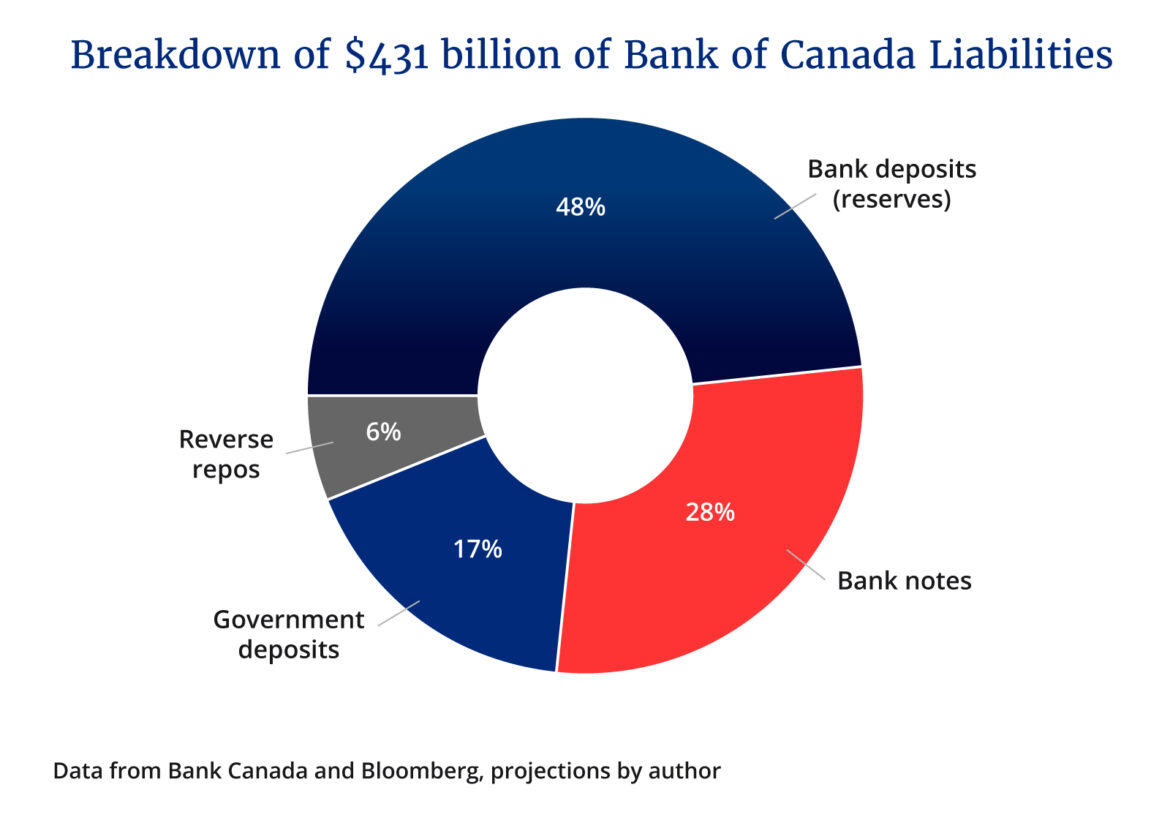

Prior to 2020, every year the Bank of Canada sent around $1 billion to the government of Canada in remittances. Those steady remittances were “seigniorage” profits: because the Bank has a monopoly on currency issuance, it can produce bank notes at close-to-zero cost, sell the notes to banks, and use the proceeds to buy bonds. The business of trading bank notes, on which the Bank pays no interest, for interest-bearing bonds allowed the Bank to self-finance its operations, “which enable[d] the Bank to function independently of government appropriations”, as highlighted in the Bank’s 2019 Annual Report. It would then send the surplus to the government. Seigniorage is the federal government’s golden goose: the feds receive a steady billion annually in exchange for granting the Bank the privilege of issuing currency.

But in 2020, the Bank ditched its ingenious zero-reserves “corridor” monetary system, in which commercial banks send funds to each other to manage their liquidity needs, for a “floor” system, in which commercial banks hold reserves at the central bank. Think of reserves as central bank money, on which the Bank pays interest. The implementation of this new system, combined with pandemic QE, means that bank notes—the golden goose—today only make up 28 percent of the Bank’s liabilities, down from 78 percent in 2019 (chart 1).

Bank notes are now eclipsed on the Bank of Canada’s balance sheet by interest-bearing reserves and reverse repos. When the Bank hikes its policy rate, it increases the interest payments it makes to banks and other financial institutions.

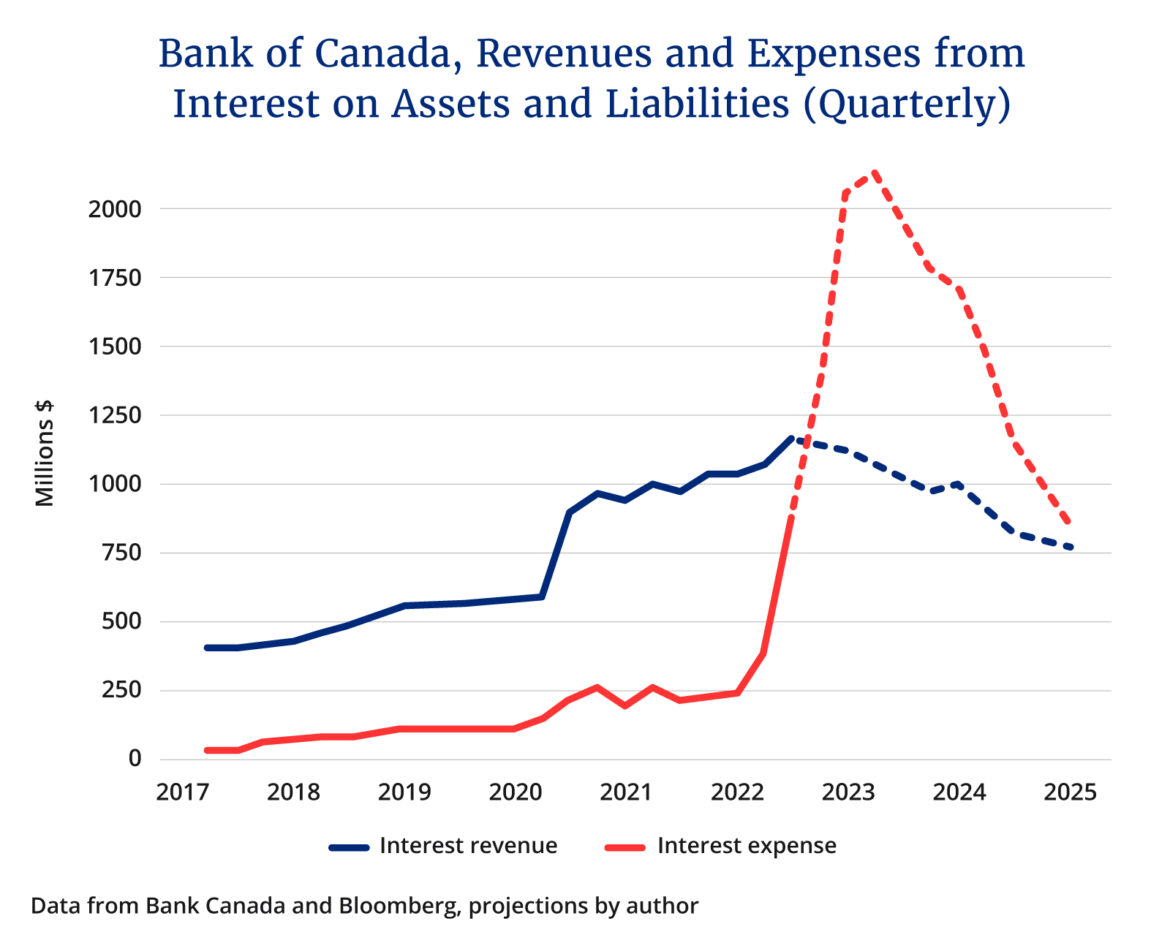

With one hand, the Bank receives interest from its bond holdings. With the other, it sends interest payments to banks. The problem is that government bonds offer a fixed interest rate, while the interest paid by the Bank on reserves scales with the Bank’s policy rate. And with Canadian rates surging, the Bank’s interest expense is about to exceed its interest revenue (chart 2). The golden goose has lost its shine.

Because the Bank does not have sufficient capital to cover the losses, the government will have to bail it out with a loan or transfer. Based on market expectations for Bank of Canada rates, I estimate the shortfall to be $1 billion in 2022, $4 billion in 2023, and $2 billion in 2024. Instead of receiving $3 billion over three years from its golden goose, the federal government will have to cover a shortfall of $7 billion, the equivalent of two percent of annual government revenues (chart 3). The Bank of Canada is clearly aware of the issue. It just stopped paying interest on government deposits at the Bank, an accounting trick to reduce the end-of-year shortfall. The Bank should be transparent about the upcoming deficit.

Now, it’s very possible the benefits of QE during the crisis outweighed the costs the government is facing today. And Canada is not alone in this position; the net cost for U.S. taxpayers will likely be even higher. But policymakers should reconsider the merits of having a central bank that is taking on interest rate risk.

By swapping reserves for bonds, the Bank effectively reduces the average maturity of government debt. When the government sells a bond to finance its spending, it chooses the optimal maturity of the bond to issue. If it wants to “lock in” an interest rate to protect itself from future changes in borrowing costs, it will issue a long-term bond, for example, a 30-year bond. But what happens to the government’s balance sheet if the Bank of Canada purchases the 30-year bond? That long-term bond is replaced by an ultra short-term bond: bank reserves, on which the Bank—and by extension the government—pays the overnight rate. Instead of locking in an interest rate for thirty years, the government locks it in for a day.

The data shows that the impact on consolidated government debt profile is immense. When we factor in the Bank of Canada’s holdings of Government of Canada bonds, the average weighted maturity of the government’s debt drops from 6.7 years to 4.7 years, rendering government borrowing costs about 30 percent more vulnerable to a rise in interest rates.

Should the unelected Bank of Canada have such an impact on the government’s debt profile? Especially since, outside of periods of acute liquidity shocks like April 2020, QE’s effects on the economy are debatable. Hindsight is 20/20, and we can’t blame the Bank for emptying the cupboard in unprecedented times. But going forward, the Bank should install safeguards around the use of its balance sheet to gobble up government debt. The Bank of Canada should also commit to eventually returning to its previous corridor system to reduce its footprint in the government bond market.