This episode of Hub Dialogues features Sean Speer in conversation with 2022 Donner Book Prize nominee and former Governor of the Bank of Canada Stephen Poloz about his nominated book, The Next Age of Uncertainty: How the World Can Adapt to a Riskier Future.

They discuss how the world is entering a new uncertain age filled with risks, from AI to climate change, how Canada can prepare itself for what’s to come, the dangers of reshoring, and the benefits of trade liberalization.

You can listen to this episode of Hub Dialogues on Acast, Amazon, Apple, Google, Spotify, or YouTube. The episodes are generously supported by The Ira Gluskin And Maxine Granovsky Gluskin Charitable Foundation and The Linda Frum & Howard Sokolowski Charitable Foundation.

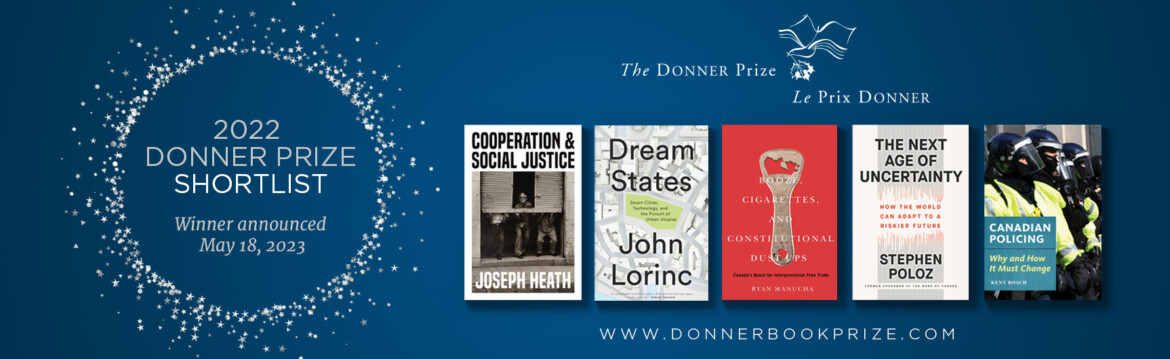

SEAN SPEER: Welcome to Hub Dialogues. I’m your host, Sean Speer, editor-at-large at The Hub. I’m honoured to be joined today by Stephen Poloz, the former governor of the Bank of Canada and author of the important 2022 book, The Next Age of Uncertainty: How the World Can Adapt to a Riskier Future. The Next Age of Uncertainty has been shortlisted for the prestigious donor prize, the best public policy book by a Canadian. The prize will be awarded on May 18th. Stephen, thanks for joining us at Hub Dialogues, and congratulations on the book and its success.

STEPHEN POLOZ: Well, thanks very much, Sean. It’s a real honour. I’ve been a policymaker all my life, so when I recognize something that’s in policy, that’s special.

SEAN SPEER: Let’s start with the book’s fundamental thesis. After several tumultuous years, those listeners looking forward to a return to normalcy are going to be disappointed. Why?

STEPHEN POLOZ: Well, what I draw attention to is there are forces acting beneath the surface that economists pretty well never mention to us. Economists are usually making forecasts one or two years ahead, and the sorts of long-term things that might be influencing these don’t enter the picture. But what I’m saying in the book is that there are actually several forces that have operated in the past that are really active now and can produce unmeasurable uncertainty going forward as they interact with each other and magnify each other’s effects. As they’ve done on major events in the past, such as depressions or the great inflation of the ’70s. These are the kinds of inferences that emerge.

SEAN SPEER: As you say, you identify five major tectonic forces that are going to reshape our political economy. What are they? And Stephen, what is their interrelationship? How do they work effectively together to create such tremendous uncertainty into the future?

STEPHEN POLOZ: Sure. Well, the forces themselves are quite recognizable. The population is aging, so there’s a demographic wave going on. People like me who entered the workforce in the ’70s are now exiting. So the population got young for 50 years, and now it’s going to get old and at a very rapid rate. Technology, people see that every day. But historically, there’ve only been three big waves of technology. Industrial revolutions, we call those. The steam engine, electricity, the computer chip, and now we’re entering the fourth, which is the digitization of everything. AI, and all those implications. The third one is rising income inequality. You can see it all around us, but the divergence in incomes—70 percent of the world has seen a deterioration in this over the past decade. The fourth one is rising debt, and I don’t have to go into detail there. Everybody knows that one. Everybody, including governments, households, and firms, are more indebted than they’ve ever been.

And the last one is climate change, or more specifically, the forced transition to net zero. That’s not necessarily Mother Nature at work, but implicitly it is; it’s a natural force, and we’re responding to it. So those five together, how do they interact? I’ll give you an example. When we have an industrial revolution, usually that leads to a period of extremely low or often deflation as you deploy new tech and it lowers costs throughout the economy. When that happens, people with a lot of debt would discover that their revenues are slowing down because of the deflation, and yet the debt at the bank is the same number as before. This leads to waves of bankruptcies, including among banks, and that’s where depressions come from. So this is the kind of force that was acting in the Victorian depression in the late 1800s or in the 1930s. So those kinds of interactions can be quite severe and totally unexpected, the way earthquakes would be from the tectonic shifts in the earth’s crust.

SEAN SPEER: I want to drill into some of these tectonic forces that you outline in the book if it’s okay with you.

Let’s start, as you say, Stephen, with the subject of technological change. Recent developments with AI would seem to validate your assessment, but what would you say to those who argue the main issue here isn’t so much rapid technological progress but actually a slowdown in economy-wide progress? That is to say, we’ve witnessed significant progress in the world of bits but less so in the world of atoms, including construction, energy, space, transportation, et cetera. In that sense, how can public policy help to accelerate broad-based progress rather than concentrated progress in parts of the economy?

STEPHEN POLOZ: Well, I think that would be a misreading of history, and maybe if we think about the computer chip: for the first, almost I would say, 15, almost 20 years, economists were searching everywhere for the productivity benefits from computers. And there was this quip in the United States, a famous economist said, “Productivity is everywhere except in the statistics.” And it was true because it’s so hard to capture something that we’ve never had to capture before. I think that’s going to be the case with AI too. But the productivity will be there, and it’s going to be absolutely everywhere. I think this is going to be even bigger than the computer chip revolution in its depth and breadth. Having an AI assistant that helps you get your job done faster, maybe do twice as much as you used to do, or have more leisure time; a big increase in our capability.

But what we know from those past revolutions is that there are a lot of winners, of course, but there are also a lot of losers. And we expect 20 or 25 percent of global workers to be displaced by this new technology. And that means they’re going to have a very challenging transition to be productive in that new world. And there you go. How do policymakers fix that? Certainly not by preventing it, it’s by facilitating it and making the transition as fast as possible. So everybody benefits. And are we equipped to do that? Sean, I’ll just say to you I don’t think so.

SEAN SPEER: You similarly address income inequality as a major concern in the coming years. What’s your case, Stephen? Is income inequality mostly a normative problem, or are there other reasons to be concerned about it?

STEPHEN POLOZ: No, income inequality is almost always the product of technological change, and I just described the winners and the losers in the initial stage, and it may take 10 years or longer for everybody to benefit. And so that’s the awkward period, right? We know that, in the end, 50 percent of Canadians worked on farms in 1867. Well, now it’s less than 2 percent and the productivity is massively bigger today. Well, that’s technology and all that doing its work for us. So that will happen again. But in the interim, income inequality will almost certainly accelerate. And the thing I pick up on the book is the other historical relationship is that anything that big, like income inequality, becomes a political problem. And so politics then adds another whole layer to how it affects the economy. Actually, it’s highly polarizing because the winners, think this is great, the losers think not. And any politician can tap into that layer of discontent and you get polarized politics that may not be able to achieve much in actually addressing the problems that people face. Look at Biden; he was elected and one of his platform promises was to address income inequality. And he has not been able to get it across the finish line. So politics can raise the problem, but then it’s reached a point where it can’t actually produce a resolution either.

SEAN SPEER: That notion of a vicious cycle is reflected throughout the book. Let me stay on the subject of income inequality. Canadian research seems to show that it’s primarily a city phenomenon. That is to say in rural communities, incomes are more concentrated in a narrow band. And so, the issue for these places may not be so much income inequality but a lack of growth and dynamism. In that vein, should policymakers be more concerned with place-based disparities than those among individuals? And if so, what can policymakers do to catalyze more investment in growth in rural and economically distressed communities?

STEPHEN POLOZ: Well, that’s an excellent lens to bring to this, and it brings a whole other dimension to the policymaker’s issue. If it was uniform, then it would be as simple as I had described it before. Canada, in fact, is one of the leading countries in terms of addressing the income distribution issue. But it’s not a snapshot issue; it’s a movie. And I’m saying the fourth industrial revolution will make it a lot worse. So we have to be ready for that. A country like the United States or the United Kingdom, where it’s the biggest deterioration in income inequality in the last decade, and you see the politics that has emerged. So imagine that, but increased fivefold or something in terms of volume and division. If the dimension, as you suggest, also crosses the rural-urban line, then we can be looking at policies that are more encouraging development that happens more regionally. Canada’s always had something like that, and yet you can’t resist the laws of gravity that bring immigrants to Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, et cetera, where the dynamism is.

But I think one of the things we’ve seen during the pandemic, this could be one of the positive side benefits of the pandemic, but I know lots of folks who now have returned home. I put quotes around home, maybe in Atlantic Canada, because they can work from home a big percentage of the year and yet still be in their original area of employ a significant time too. So I think that may help this issue that you’re raising because you don’t have to move forever. You can move half the time. And so more of that commuting type of style working from home could make a big difference. Well, how can governments help? Well by facilitating it, right? So it’s not about encouraging companies to get people back in the office; it’s actually encouraging people and companies to be innovative about how we actually deliver work and making it just as easy to do. Whichever way you choose. A lot of things are built around a standard work relationship, and I think the employer-employee relationship is fundamentally changing. Indeed, all the power is shifting to the employee. So if we don’t respond to them, the employees will have the power to make it happen.

SEAN SPEER: That’s a great segue, Stephen. You anticipated my next question. As you say, the book envisions a world in which market power is shifting from employers to employees due to tight labour markets. How much would those trends in and of themselves have anti-inequality consequences?

STEPHEN POLOZ: Well, let me begin with this. The share of income in the world going to workers is at the lowest point ever measured. And if you go to Piketty’s book, Capital, you’ll see he’s measured it over 400 or 500 years. And so it’s at the levels where we can look for things like revolutions that actually upset the system or overthrow the system, a feudal system, or whatever your system was, when a revolution happens. So it is a danger point. What we can expect to see, therefore, is through the forces we’re just describing, there’s going to be an upturn in the share going to workers, whether it’s because unionization sees a renaissance or because companies get in front of it, like we’ve seen Amazon or Walmart boosting the starting wage above the official minimum wage. That’s to prevent some of those side effects.

I think that kind of intelligent adjustment is going to be seen more and more. And as we go forward, you’re going to feel that power. If you’re an employer, you cannot get the job done. You simply can’t conduct your business without the people. And so you’re going to pay them better. And as you do that, the wages will rise, and you’re going to invest more so they have better capital equipment—the new technology we talked about. So, as we say as economists, a higher capital-labour ratio than before. And that will justify that higher wage and a higher productivity level to go with it. It’s hard for people to picture that because, for 50 years, workers have been in surplus. They think that’s normal, but the new normal will be more like the 1950s than it’ll be like the ’90s.

SEAN SPEER: Staying on the topic of productivity, you argue that our efforts to smooth out the business cycle through fiscal and monetary policy interventions have worked successfully, but that an inadvertent consequence is that these policy choices may have contributed to our poor productivity. Do you want to elaborate on this insight, Stephen? What’s the transmission feedback here?

STEPHEN POLOZ: Yeah. I think most people have heard of Schumpeter’s notion, which is creative destruction, that the growth, the dynamics of an economy are actually fueled by the destruction of dead wood, or think of a forest that has to have a forest fire now and then to clean out the accumulated debris for its long-term health. There’s this argument that economies need to do the same thing with companies that hit a stop point. They just can’t grow anymore. They’re not employing more people; they’re just stuck. Usually what happens is somebody comes along and steals their lunch on them, competes them out of business, that’s a force, or their banker will put them out of business because they can no longer manage things. But of course, recessions have been a very powerful cleanser historically, and we’ve had a pretty good recession pretty well every 10 years or so.

But if we keep putting them off and we manage them, that’s, of course, better for society. But one of the side effects could be, well, you never get the cleansing. Now, I, for one, think that it’s really the bank’s job, the lender’s job, to make sure that they’re not lending to companies that are about to fail. But the fact is, we could have an accumulation of companies that might have failed but didn’t. And that means the average productivity growth rate is lower in our economy than it would be if we’d had that. And so I’m hopeful that the forces of competition, especially for workers, will make the big difference as we go forward, and we’ll see more of Mother Nature doing the work. We shouldn’t have to have people unemployed in order to put that pressure on the economy. I don’t think so, but historically, you’re right, it has been. And so what we need, I think, is maybe a little bit more responsibility carried by lenders because it’s really their job to be the police of those companies they’ve lent to.

SEAN SPEER: Let me follow up on that response. You make the case in the book that aging demographics are going to put downward pressure on economic growth at a time when growth is necessary to boost incomes and pay for the rising demands on government. Do you think there’s a way out of the slow growth that we’ve experienced now for something like two decades? Or do you think, as some have argued, that we’ve essentially plucked the low-hanging fruit of invention and innovation and that step changes in economic growth and productivity just aren’t possible?

STEPHEN POLOZ: No, I’m an optimist on this front, Sean. I mean, that’s the lesson of history. You look at all the bad luck we have along the way. We know good luck has outweighed bad luck; otherwise, we wouldn’t be sitting here. But the fact is that productivity growth, it comes in those waves, and we’re just entering a big one right now. By my measures, we added at least 10 percentage points onto everybody’s standard of living just from the computer chip from 1995 to 2005. That’s 1 percent growth per year, okay? And so imagine if that’s what we’re faced with at least that much in the AI revolution, the digitization revolution. Well, how do we make sure we get it? Well, we make sure that we have the right environment for companies to make the right decisions, and that they’re not stifled in any way.

Well, we could have a meeting and close the doors with enough politicians there and we could find a list of a hundred things worth getting rid of which are slowing us down. And so I think that that right there could be a project. Let’s get the things that are in the way of growth and get rid of them, whether they’re rules, regulations, streamlining. You’ ‘ve got to knock out some red tape, put it simply, in order to make it possible to be a dynamic company. And we’re really good at adding additional rules but never taking any off.

SEAN SPEER: The book discusses climate change as one of these tectonic shifts. Do you think about the energy transition and decarbonization as managing a threat or is it itself a potential source of growth and progress?

STEPHEN POLOZ: I see it in a positive way. Although what concerns me is the arbitrary of it, even to the point where people who are very adamant about net zero forget to use the word net, they end up talking about zero and leaving things in the ground, and so on. We know that society sits on a three-legged stool. Those three legs are food, water, and energy. And so as society progresses, we’re going to need even more energy than we had today. It’s not about switching energy; it’s adding more capacity for the people who cooked their dinner last night over a dung fire. They should have access to electricity. If you’re going to grow energy use by 60 percent over the next 30 years, which is most likely, you will still need 50 percent of your energy coming from traditional sources just in order to keep that stool sitting up.

Well, that just means we have to get our heads around carbon capture very well, and that’ll allow us to walk and chew gum at the same time. I know it sounds like rocket science, but literally it is not rocket science. We understand the technologies that will be expensive at first, but we know we can do this. And so if we can get our heads around the idea that it’s got to be net and make our investments upfront in carbon capture, we know that we can get to 2050. But right now we’re too preoccupied with zeros and holding back energy development to fuel the world. And things like old plastic straws and so on—these are by themselves interesting or probably beneficial ideas, but they’re missing the big picture, which is that Canada can help clean up the world, and we’re not really ready to do that yet.

SEAN SPEER: In the book, you make something of a defence of the benefits of trade liberalization, which is increasingly a less prominent argument in today’s public policy discourse. Let me ask a two-part question. First, do you think there’s anything to the arguments against how we’ve pursued trade liberalization and globalization in recent decades? And second, what if anything can be done to rebuild support for such an agenda? For instance, should modern trade agreements permit more scope for national government in policy areas like intellectual property or procurement, or whatever?

STEPHEN POLOZ: So you’re onto some good things. The last part there, which is to say that carte blanche free trade, as we learn in our textbooks, that just doesn’t seem to be on. There are always going to be exceptions, and the exceptions grow by experience. And we experienced some things during the pandemic, and now we have these tensions, both technological and geopolitical, with China and others in Europe, Russia. So we’re not going to have a perfectly liberal world, are we? And there’s going to be strategic reasons for security purposes, let’s say. But I’m afraid that that’s a bit of a slippery slope. It’s awfully easy to make that argument for many things. So we’re going to have to have in front of people a better description of what it is they would be giving up. And I’ll give you a quick example during Donald Trump’s presidency, he said one of the things he was going to do is reshore kitchen appliances.

So when you buy a Maytag and assist made in America on it, well, it didn’t used to be. And so that all sounds like it created a lot of jobs. It did not create a lot of jobs, and it added to the cost of living to the average American household by close to $900 per year. But no one talks about that, okay? So what did we give up in order to achieve something which actually may not be that big. But if we want security in something, we know it’s going to cost us something. And the question is, what’s the price we should be willing to pay? So we need actually CEOs to be more transparent about what some of these things will do to their employees, and their companies. They’re often quite quiet when we have these debates.

And so it sounds like economists like me with abstract things and leap-of-faith analysis, really. And it’s too bad because the oldest lesson in economics, you don’t do your own dry cleaning, right, Sean? You don’t grow your own vegetables probably. People specialize in those things, and you pay them to do those things for you while you do something much more valuable in your space. Well, all that’s just trade in your neighbourhood as opposed to trade across borders. Trade is trade, exchange, and we cannot have our standard of living, and especially here in Canada without it, we can’t be cutting off imports from somewhere and expecting them still to buy our exports. I mean, that’s just crazy. So we have to be very careful on this front. We should be leading proponents of liberalized trade, and if we’re going to go with friend-shoring for strategic reasons, oh, by the way, there are an awful lot of low-cost places that can be our friends in the trade system.

SEAN SPEER: Great answer, Stephen. Let me just follow up specifically with respect to reshoring or friend-shoring. It seems to me listeners would instinctively understand why we may have a case for intervening in markets to ensure we have some amount of vaccine production capacity within our borders, but that the case for domestic t-shirt production may not hold up. What are some principles or insights that can create something of a framework for making those types of judgments?

STEPHEN POLOZ: Well, that’s exactly what I meant by a slippery slope, Sean. What’d you say? For example, we had a shortage of masks during the pandemic, and so it turned out the fastest way to get masks was to bring them in from China. Well, does that mean that if we have another pandemic, we wouldn’t be able to do that because we’ve tried to friend-shore, or do we need to have those made right here in Canada? Maybe. I mean, those are very hard judgements to make, and that’s why I’m just saying we should have in front of us enough concrete analysis and not rhetoric, right? But true analysis, this will cost this much. Maybe you need an independent entity whose job it is to help assess the pluses and minuses objectively without political influence, and so on. And let them be the judge so that people can say, “Yes, that would be crazy.”

But I think it will be very hard to manage politically when politics continues in the way we talked before. And so I hope that companies will play a stronger role in describing how we can still get things done by de-risking our supply chains. That’s not the same as black and white reshore, offshore, friend-shore. It’s like, “Well, instead of getting it from just one country, I’m going to get it from three different countries, and it may cost me 2 percent more to have that structure, but I’ve bought something with that insurance: better certainty of supply.” And you continue to use the global trading system. That’s why I think where companies would like to go, but I’d like to hear them talk about it more.

SEAN SPEER: You’ve been so generous with your time, Stephen. I just want to put a couple final questions to you. First of all, in the geopolitical context that you’re describing, there seems to be an increasing assumption that it’s Canada’s interest to effectively double down, for lack of a better term, on continentalism. What do you think are the opportunities and challenges associated with deeper economic integration with the United States on some of these issues?

STEPHEN POLOZ: Well, I think those are very large benefits. Throughout my career, there’s always been a drumbeat to try to reduce our dependence on the United States, diversify more. And of course, diversification is always a good thing. It de-risks your business proposition. But really reduce your dependence on the largest, most dynamic, most energetic, most innovative economy on earth. Is that really something that’s worth trying to do? And we so there’s an awful lot of opportunity here, and not just the United States, because obviously, our third partner there in Mexico has a wealth of opportunity for a development path. And so there’s a lot to be had there, but you don’t need to cut off the rest in order to do that. So I’m reluctant to go one way.

And one thing I wanted to say for sure is that all along, we always knew that the China globalization, China supply chain, would never be a permanent thing. China would move up the value curve, it would begin to cost more, and there’d be somebody else with a less expensive but same proposition for us to transition to. So it was always a living thing, and it was not going to just be forever the way it was set up. And in fact, right now, there’s like Vietnam, Thailand, Philippines. These are places where you can do exactly what we’ve been doing in China for the last 10 or 15 years. We can do it now for the past that we did in China 15 years ago. So it’s a natural process, and we should not be standing in the way of it or trying to turn it into politics. Politics should be making sure those avenues are available to companies who can do these things on behalf of their employees for sustainable jobs.

SEAN SPEER: What should we make of the recent string of developing countries devaluing their currencies and seemingly moving away from the U.S. dollar? What do you make of that, Stephen? And what does it mean for Canada?

STEPHEN POLOZ: So the natural state of the world is probably not one where the U.S. dollar is so dominant as it has been in the post-war period. It’s incredibly dominant, and it doesn’t need to be that dominant to be dominant, if you get my drift. And I do think that there’s this notion, which I think is healthy, is that if there’s more of a competition between international currencies such as the Euro or, for that matter, Sterling, that goes back a ways, but it’s still an important vehicle currency, and indeed, the renminbi, that can be an important international vehicle currency. And there’s absolutely nothing to prevent these currencies from all being internationally exchangeable and facilitating trade in certain orbits. There’s absolutely nothing to stand in the way of that, and it will not be negative for the United States or for Canada. So I’m searching for a reason to be worried about this. I think it’s a natural thing that countries try to grow that part. It’s certainly natural for China to try to internationalize its currency. It’s part of the development path of a major economic entity.

SEAN SPEER: Let’s end on a positive note. Given everything we’ve discussed, why are you still a self-described optimist?

STEPHEN POLOZ: Well, there’s this whole saying that the cream always rises to the top. It’s inevitable. And so, through the combination of hard work and thoughtful investing, we’ve always managed well here in Canada. I think if we allow those natural forces to persist through time, we’re going to be fine. But where we can get our do things wrong is we get in the way of it through good intentions. We make it harder for people to do. And if it looks easier to do somewhere else, like in the United States, that could happen. And that’s one of the things we’ve seen over the last five to 10 years, is when you have a decision of where to put the next bunch of money into the ground or into your operation, you can hedge your risk by investing in the United States and maybe grow more. We certainly had that happening during the Trump presidency. And I think it’s still a live issue among Canadian companies. Some of those investments will never get back again unless we really make it just as easy to do business here as there.

SEAN SPEER: We’ve been talking about the Donner Prize-shortlisted book, The Next Age of Uncertainty: How the World Can Adapt to a Riskier Future. Stephen Poloz, thank you so much for joining us at Hub Dialogues.

STEPHEN POLOZ: My pleasure, Sean. Thank you.