Trust is a core currency in democratic and prosperous society.

Growing concerns about the decline of trust are valid and deserve discussion, especially as we consider the resulting drop in the impact and social benefits social institutions provide.

Unfortunately, these discussions often take place without fully appreciating that trust is contextual and is not unlike banknotes. Trust needs to be exchanged into specific currencies if its benefits are to flow from various social institutions. Each context requires its own currency. So, while “trust” is relevant to politics, business, media, and non-governmental organizations, dealing with the decline in these different settings will require solutions specific to them.

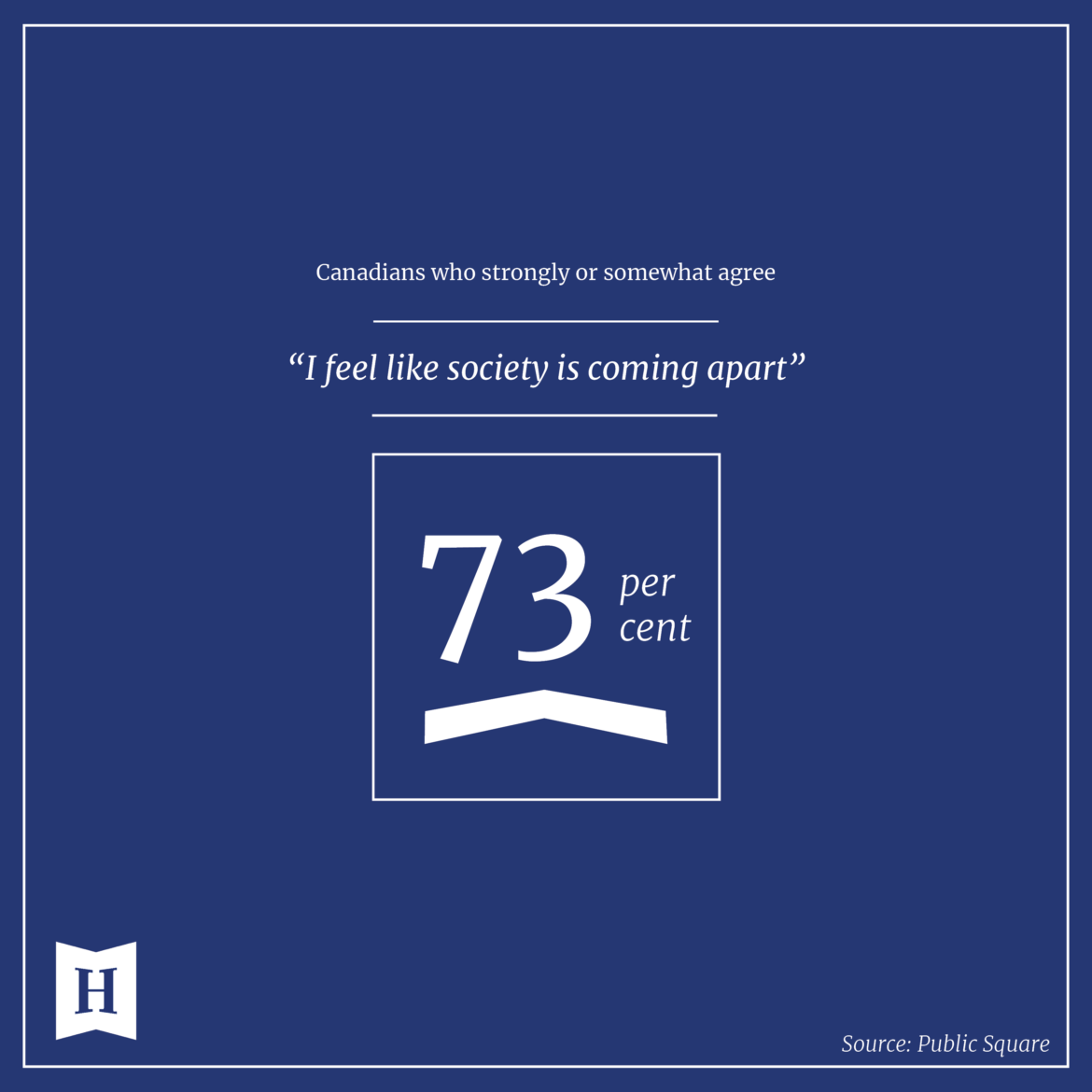

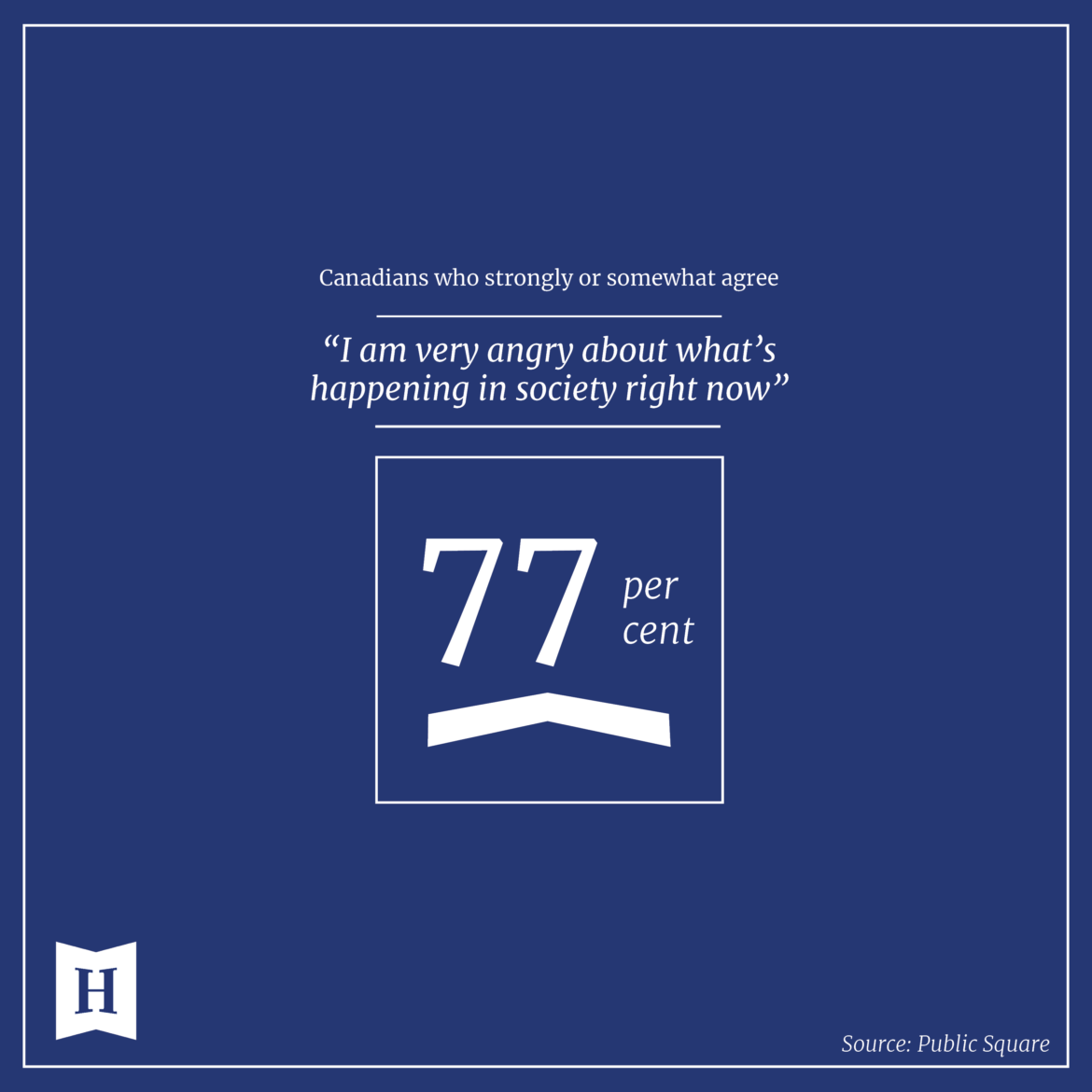

As recent polling shows us, trust in our vital institutions is low.

Parsing the concept of trust invites us into the science of social capital, a term that has become a common part of the social science vocabulary only in the past few decades. The concept is of older vintage, perhaps best understood as what Alexis de Tocqueville was getting at when he wrote Democracy in America in 1840. In brief, social capital involves voluntarily working with and through institutions other than government to achieve social good. Understanding how citizens viewed and dealt with their neighbours when government wasn’t looking has been a key component to understanding the health of a democracy long before the words we use today were in vogue.

With that in mind, it’s interesting to look at January’s Edelman Trust Barometer, a two decades-old annual measurement of trust in 28 countries. After documenting the continuing decline of trust in credibility almost right across every institution, Edelman found high trust in business. (Canadian respondents viewed their employer as their most believable information source.) Even more interestingly, a full 65 percent agreed that CEOs “should step in when government does not fix societal problems.” More than 60 percent of both consumers and employees indicated that economic choices were the means to drive change. Almost half of employees (46%) indicated, “I am more likely now than a year ago to voice my objections to management or engage in workplace protest.”

The popularity of specific economic levers to influence decision-making — strikes, lockouts, boycotts, tariffs, subsidies, preferential policies, closed bidding — change over time. However, the use of economic leverage to achieve non-economic results has always influenced the exchange of labour, goods and services. But the implicit premise that somehow this will remedy the trust deficit in other institutions, specifically government in this case, is like offering pesos to buy land in France. Euros are the expected currency and the currency mismatch confuses rather than solves the problem.

We need to use the right currency in the right context.

There are at least two parts to the challenge of trust: the core basics common to all institutions and the institution-specific requirements.

The first part includes things like accurate information, ethics, honesty, and reliability, to mention just a few. These are essential ingredients no matter the context. Character matters and is inexorably tied to trust. Words must also reliably communicate dependable information.

The second part of trust involves the added dimensions of trust that need to be accounted for if the trust deficit is to be resolved. Each institution has its own task. Government is about dispensing justice, treating people fairly and equally, and ensuring security. Business is about investing inputs to create greater outputs, stewarding the resources they are given into goods and services that have value for their customers. Media is about informing people as to what is happening, providing information with courage and not skewing it to deceptive outcomes. Faith institutions are about truth and service of others. Families are about love and fidelity.

The basic, and usually overlooked, premise is that each social institution has its own leading functions or characteristics, which it must faithfully serve or express for it to maintain or regain its trust. So, when business is expected to “fix” government, or any other institution steps out of its lane to “fix” different other institutions, the result is rarely progress or an increase in trust.

So how then how can society make deposits in our trust accounts? And how can the various institutions withdraw this in order to contribute to flourishing?

There are no quick fixes but a few less-considered principles merit reflection.

First, recognize that all institutions have both a private and public dimension. Marriage and family, on the one hand, are very personal institutions, but let’s not overlook their public implications. They remain the primary context in which future citizens and taxpayers are born. Fertility rates are essential to any GDP and economic prosperity forecast. Religion is another example. Were it not for the $67.5 billion that faith institutions contribute to Canada’s GDP, a full range of services we take for granted (especially education and social services) would look very different or disappear. Every institution, while having a primary group of participants and stakeholders, also serves all of society. Through its behaviours it is either a net contributor or withdrawer on our collective trust accounts.

Second, although there are various institutions that can deliver on specific outcomes, some are better suited for the task than others. I don’t doubt that teens who join gangs build an impressive skillset of teamwork, esprit de corps, other practical know-how that could have significant economic and public benefit when applied in the workplace in later life. I also don’t doubt that most of us would prefer a society in which young people learned these skills through sports teams or community youth programs. A healthy society needs trust deposits from the full range of healthy institutions. No single institution, including government, is in a position to fill the gaps by the failure of any other institution. And just because an alternative institution may fill a vacuum when one isn’t doing its job well, that doesn’t mean the result will be interchangeable.

Third, trust is not a value-neutral term. Our egalitarian age is preoccupied with overcoming historic prejudices, which is important. Every person, regardless of their ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or other distinguishing aspect of their personhood, deserves respect based on the simple fact that they are a human being created with dignity. And those categories, which too often are used to divide people, should not become a shorthand for distinguishing those who are trustworthy from those who are not. But that doesn’t mean that respect is a synonym for trust. Trust is earned and our trust for others is increased or decreased by our past experiences with them. Even as we correct for past misapplications of categories being unjustly used as proxies for trust, it is naïve to think that consequently trust is an egalitarian concept.

Yes, trust is on the decline but contrary to public opinion, assuming the Edelman take is accurate, business and commerce can’t fix what is broken.

The trust bank requires deposits in the right currencies from the full range of social institutions healthily functioning. It also calls for a much more multi-dimensional take on things than the singular “this will fix it” solution. It requires us to look around and within to see where opportunities for growth might work.

While the situation is surely serious enough to warrant broad social dialogue and a consideration of how trust and flourishing interact for the common good, it also requires individual action as we interact within our families, communities, places of work and other institutions we are part of. When we live not just for ourselves but with a concern for our neighbour in our everyday lives, the interest on these trust deposits will result in an overall value that might even be measurable the next times the surveyors come along to audit the books.

Recommended for You

Canadians are drinking the least amount of alcohol in the last 20 years on average: Statistics Canada

Auston Matthews doesn’t owe Canada a thing

If Canada wants stronger communities, it must make volunteering easier

After snubbing Don Cherry for over 40 years, the Order of Canada should drop politics and appoint him

Comments (0)