It will be years before the personal pain and emotional experiences of this pandemic make way for a dispassionate assessment of what was done well and which countries had the best response.

Polling suggests the public will give governments the benefit of the doubt for once-in-a-century pandemics, making them non-political events. But only until it becomes clear your country is not keeping up.

The slow roll-out of vaccines contributing to today’s awful third wave of COVID-19 infections is now dominating Canada’s political debate. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government could soon be experiencing the reverse scenario to the Conservatives in Britain, who endured widespread criticism at the outset, only to be lauded a year later for the best vaccine roll-out of any major country.

Two areas will reverberate down the years as Canadians try to make sense of their government’s record. Firstly, to what extent the country’s lack of domestic vaccine manufacturing capacity left it woefully ill-equipped for the pandemic and for quickly deploying the most effective tools to allow the economy to reopen sooner.

Secondly, whether the support schemes did their job and if the fiscal impact — and the cratering of the public finances — could have been a different story if government spending had not already been so high.

On the first question, if more onshoring is deemed necessary in a world where globalised supply chains seize up in a crisis, then it should not be allowed to become a partisan issue because these capabilities have to be developed over decades.

Unlike the human impact in lives lost, the raw fiscal cost of this pandemic is tangible.

The recent federal budget boosts life sciences spending by $2.2 billion over seven years, including allocating $59.2 million over three years for bio-manufacturing of vaccines, and calls domestic vaccine capacity “essential to our national security.” A striking statement that by implication means it took a global pandemic for the federal government to recognise a key element of its national security was not really optional. These are the industrial foundations that the U.K., France and even smaller nations like Australia have invested in for years, but this needs bipartisan commitment and something akin to a modern industrial strategy.

The second question is more difficult, because every country has taken a massive fiscal hit and the policies used to fund the furlough schemes and keep businesses afloat were adopted in haste and will be evaluated at leisure. Few dispute that schemes like CERB, or something like it, were needed. The stimulus spending made the lockdowns tolerable, and the lockdowns — to a degree that is still contested — contributed to slowing the virus’s spread and saving lives. But was it enough? And if it wasn’t, what else might Canada have done that it could have realistically afforded in 2020?

Unlike the human impact in lives lost, the raw fiscal cost of this pandemic is tangible and if the price to pay for tackling it was national debt at World War II levels, and increased taxes for perhaps a decade or more to come, it is important to know if the fiscal response worked. Did it save businesses from going under or just forestall it by a few months?

One way to gauge how this pandemic has affected businesses is to ask them. The consultancy I work for, Public First, surveyed companies in Canada to understand how they had been affected and what they thought about the government’s response. In a representative national survey of businesses conducted earlier this month, a majority (59 percent) of businesses report their revenues have declined compared to 2019, against just a fifth (19 percent) who say they have stayed the same. The impact seems to have been worse on smaller businesses, with a quarter of firms employing fewer than 10 people saying their income is down by more than half and almost a third of sole proprietors saying their income has declined by over 50 percent.

There is a lucky minority of businesses who say their revenue has grown since the same period in 2019, but these are more likely to be larger companies. In a hint to the long-term legacy of what the pandemic has done to customer behaviour, almost 1 in 6 businesses said “the COVID-19 pandemic caused my firm to lose customers and become unprofitable.” Again, this is a statement that more smaller companies agreed with.

Given these results, it is not surprising that businesses generally think the government has not done enough. When respondents were asked about the government’s handling of the pandemic a nuanced picture emerges.

A majority of businesses supported the early action to close the borders and there was general support for the idea that provinces were left to decide too much and the federal government should have played a bigger role. However, respondents split 46 to 18 in support of the statement “the Canadian government prioritised making emergency payments to individuals at the expense of direct support for businesses” (with 35 percent neither agreeing or disagreeing) which might suggest that there is underlying resentment among business owners.

The vaccine failure seems to have been noticed. By 64 percent to 12 percent Canadian businesses agreed that “the Canadian government was not fast enough in securing shipments of COVID-19 vaccines and has taken too long to approve vaccines for use.”

And in a question that could have delivered a much more impressive result last year, 43 percent agreed that “the Canadian government handled the pandemic far more successfully than other countries” (with 30 percent disagreeing).

In a possible sign of Canada’s deep-seated reasonableness, 60 percent of businesses surveyed agreed that “the Canadian government was not well prepared for the pandemic but did an OK job in the circumstances.” This is the benefit of the doubt that may end up saving the current government from major political blowback, although vaccine progress in next few months will decide whether that last question will deliver a radically different result by the fall.

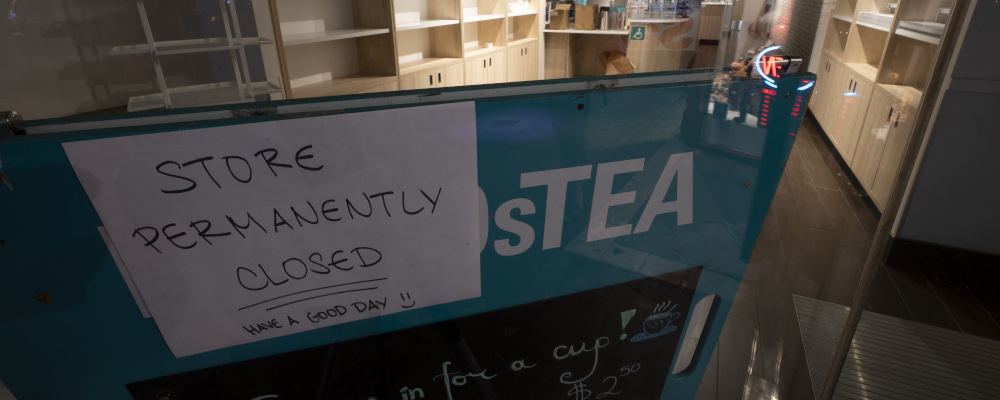

As the federal budget unveils a raft of new support schemes for employees and businesses, this poll gives a sense of the pandemic’s impact on the “real” economy and it is clear that businesses have been hugely impacted already and many of them feel let down. It is also striking that despite the generous taxpayer support provided by provincial and federal governments since last spring, the lockdowns were more than many Canadian businesses could weather, and for plenty of companies they have already drowned. Each of these failed businesses is a human story of a lost dream, of life savings being wiped out and new opportunities lost, and it will have an electoral impact eventually.

There may be another federal election before it becomes clear how the pandemic has materially affected businesses, and how much the support schemes have cushioned ordinary voters. But we do know there are hundreds of thousands of people who will never recover economically from COVID-19, even if they avoided contracting the virus themselves.

Recommended for You

‘Our role is to ask uncomfortable questions’: The Full Press on why transgender issues are the third rail of Canadian journalism

Need to Know: Mark Carney’s digital services tax disaster

Sean Speer: Investing in critical minerals isn’t just good business, it’s a national security imperative

Theo Argitis: Carney is dismantling Trudeau’s tax legacy. How will he pay for his plan?