Two episodes from this past week have once again underscored a lack of seriousness on the part of Canadian policymakers in thinking about the growing geopolitical and technological threat posed by China.

The first is the renewed speculation that SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) may have originated in the Wuhan Institute of Virology in China. This theory, which has long been rejected by Chinese officials and marginalized by Western political and scientific elites, is now gaining momentum due to evidence collected by a small yet persistent group of “amateur sleuths.” In response, the Biden administration has reversed its characterization of the lab-leak theory as a “conspiracy theory” and recently instructed U.S. intelligence agencies to intensify their investigation into COVID-19’s origins.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has been far slower to concede that his government’s initial resistance to this notion was unjustified and overstated. He’s also continued to dismiss questions about the risks of research collaborations between Chinese military researchers and Canadian scientists on highly sensitive matters in general and reports that two Canadian scientists with ties to China were recently fired from the National Microbiology Lab in Winnipeg due to national security concerns in particular.

Last week, when asked in Parliament about this specific national security case, Trudeau instead spoke generally about the importance of tolerance and diversity and the risks of anti-Asian racism. His health minister, Patty Hajdu, went further and accused the opposition of “playing a dangerous game.”

It’s hard to see how these parliamentary questions, even if posed with typical partisan rhetoric, are more dangerous than the potential of a Chinese cover-up of COVID-19’s origins or the national security risks of Canadian scientists shipping highly infectious diseases to the Wuhan Virology Institute. The former may have bigger geopolitical consequences, but the latter is more emblematic of Canada’s ongoing lack of a systematic and realist China strategy.

The government’s divisive and partisan answers are themselves characteristic of this deeper problem. They reflect an ongoing failure on the part of Canadian governments, universities and other public and private institutions to fully understand the strategic threat posed by China. Our institutional positioning vis-à-vis China continues to be marked by a set of disproven neoliberal assumptions about the liberalizing effects of economic and non-economic cooperation. Our China policy is stuck in a Fukuyamaian “end of history” view of the world.

Although virtually every other country has moved on from this policy failure, the Trudeau government has stubbornly persisted. Consider, for instance, its ill-fated scheme to collaborate with Chinese firm CanSino to produce a coronavirus vaccine. The idea that Canada ought to partner with a Chinese company on something as important as the COVID-19 vaccine in the middle of heightened bilateral tensions is self-evidently dumb. It’s perplexing that neither Cabinet ministers nor government officials saw the inherent problems.

Discerning the source of this blind spot can be challenging. It may be the allure of the Chinese market for Canadian businesses and investors. It may reflect a latent anti-Americanism among our cultural and political elites who cheer China’s rise as a counterweight to the United States and a return to a bipolar world. Or it may be a well-intentioned yet ultimately misguided expression of the recent emphasis on anti-racism.

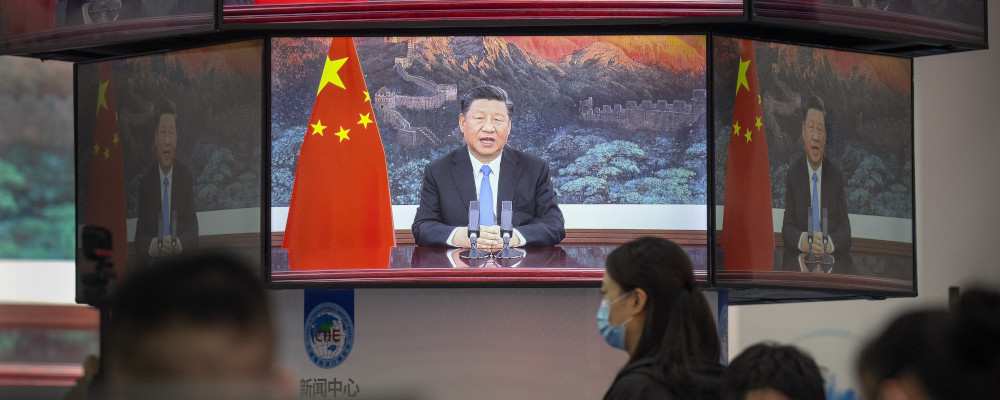

But whatever the underlying causes, the Canadian government’s response to growing speculation about COVID-19’s origins follows a familiar pattern: Ottawa persists in its childlike inclination to grant the Chinese regime more deference and trust than is reasonable. Our weak positioning on China is increasingly making us an outlier among peer jurisdictions across the Anglosphere and other advanced economies.

Even when we do take tougher positions, they tend to be non-strategic and unfocused half-measures. Which brings us to the second episode related to China this past week: Ottawa’s imposition of tariffs as high as 300 percent on upholstered furniture from China.

While Ottawa is imposing tariffs on furniture imports, the Biden administration has announced tough new restrictions on U.S. investment in 59 Chinese companies linked to military and surveillance technology.

The tariffs, which took effect in early May, are due to concerns that the “dumping” of low-cost, highly subsidized Chinese goods is harming Canada’s domestic furniture-manufacturing industry. In its 117-page statement of reasons, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) outlined in some detail how a number of Chinese furniture manufacturers benefit from a panoply of financial and non-financial supports in the form of government policy.

There’s no reason to doubt the CBSA’s analysis or the government’s tariff decision. There’s plenty of evidence that Chinese manufacturers do benefit from unfair, non-market trade practices in this sector and others. We also know that this has had negative consequences for Canadian firms and their workers. The so-called “China Shock” is estimated to have destroyed at least 105,000 Canadian manufacturing jobs between 2001 and 2011 alone.

The problem here, then, isn’t the imposition of retaliatory tariffs per se. (Libertarian screeds against so-called “Tariff Man” may be interesting fodder for online message boards or university debate societies but generally don’t have much real-world utility.) Instead, the issue is that a one-off tariff on Chinese furniture imports divorced from a broader set of industrial and geopolitical considerations is too myopic and marginal. It doesn’t address the deeper questions about Canada’s ongoing economic relationship with China.

One just has to read the Chinese government’s Made in China 2025 strategy to see that its goal isn’t to be a global leader in couches and chesterfields. China’s long-term strategy involves developing technological advantages in sensitive and strategic sectors such as next-generation information technology, advanced manufacturing (including advanced robotics and artificial intelligence) and emerging bio-medicine.

With this in mind, it seems backward-looking and fragmentary to impose tariffs on upholstered furniture without articulating a broader view about how Canada will manage two-way investment and trade in these new and evolving sectors. These forward-looking technologies, which tend to have monopolistic qualities and dual commercial and military purposes, are where the future lies.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has described them as the underpinnings of a new global rivalry between “techno-democracies” and “techno-autocracies” in which the competition is over technological advantage and the application, use and regulation of these modern technologies.

It’s an inadvertent study in contrasts, therefore, that while Ottawa is imposing tariffs on furniture imports, the Biden administration has announced tough new restrictions on U.S. investment in 59 Chinese companies linked to military and surveillance technology, including telecommunications manufacturer Huawei Technologies. Expectations are that President Biden may encourage his G-7 counterparts to adopt similar measures at the forthcoming meetings in England.

The key takeaway from these separate yet related episodes is that the Canadian government needs to update its thinking about China. We’re currently disadvantaged by mentality. The Chinese are systematically pursuing technological dominance in key sectors and we’re focused on futons. It’s time to get serious. Canada needs a new China strategy.

Recommended for You

Christine van Geyn: We must protect freedom of expression in Canada—yes, even for controversial American worship singers

Nathan Pinkoski: Canada is a moderate country? Nothing could be further from the truth

Need to Know: Do Trump’s new tariffs even matter?

‘Debacle’: How Toronto’s condo bubble could lead to tens of billions of dollars in losses