Canada’s economic recovery from the ravages of COVID-19 is surprisingly strong. And it seems poised to only grow stronger from here.

Canada may very well have three-in-four eligible individuals fully vaccinated by the end of July. These highly effective vaccines will almost surely mean that what’s been unsafe for the past year-and-a-half will soon (thankfully) become normal once again. And as provinces ease public health restrictions, activity in many sectors will rebound through the summer.

This is unquestionably great news but it may pose an interesting problem for some of the federal government’s recent spending plans. Or, at the very least, how those spending plans are pitched to voters.

Is fiscal ‘stimulus’ needed?

The federal budget for 2021, released barely more than two months ago, centred on “stimulating a rapid recovery in jobs.” The very name of the budget — “A Recovery Plan for Jobs, Growth, and Resilience” — makes that clear. This was a key rationale for many of the spending proposals it put forward.

To be clear, the bulk of Canada’s deficit was to directly cushion the financial burden that pandemic disruption has caused families and businesses. This wasn’t a “stimulus” so much as a “bridge” to get Canadians to the other side of this extraordinary situation. But looking forward, significant fiscal stimulus is on the way.

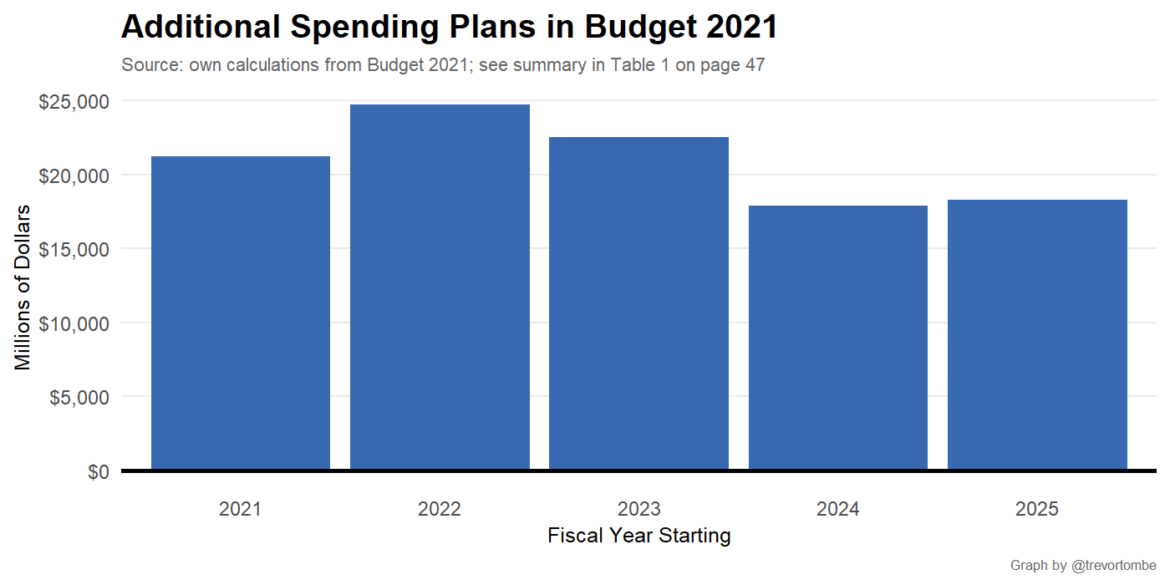

Last November, the federal government planned for $100 billion in what it explicitly called “stimulus.” In Budget 2021, it confirmed this would go forward. It’s tough to track each dollar, but excluding measures directly related to healthcare and income support to individuals and businesses, there is indeed nearly $100 billion in additional spending measures detailed in the budget. That’s large, and is spread across multiple years through to 2025.

The size and length of the planned stimulus is deliberate. Some argue the previous Conservative government pulled back on its fiscal stimulus following the financial crisis too quickly. The government implicitly argued as much when the finance minister said, during the budget speech, that “the world has learned the lesson of 2009 — the cost of allowing economic hardship to fester.” This was widely observed as an argument for larger and longer stimulus.

The basic premise is straightforward: government expenditures can utilize workers and machinery that would otherwise go idle, and borrowing to fund this can itself (potentially) lead to increased labour supply by individuals and therefore increased employment. Estimates vary, to be sure, but a dollar of fiscal stimulus might add 60 cents to $1 to overall economic activity. (For a great review of the research literature on this, see this recent article.)

The case for stimulus today, however, has weakened as the economic situation changed for the better. Dramatically so.

A strong economic rebound

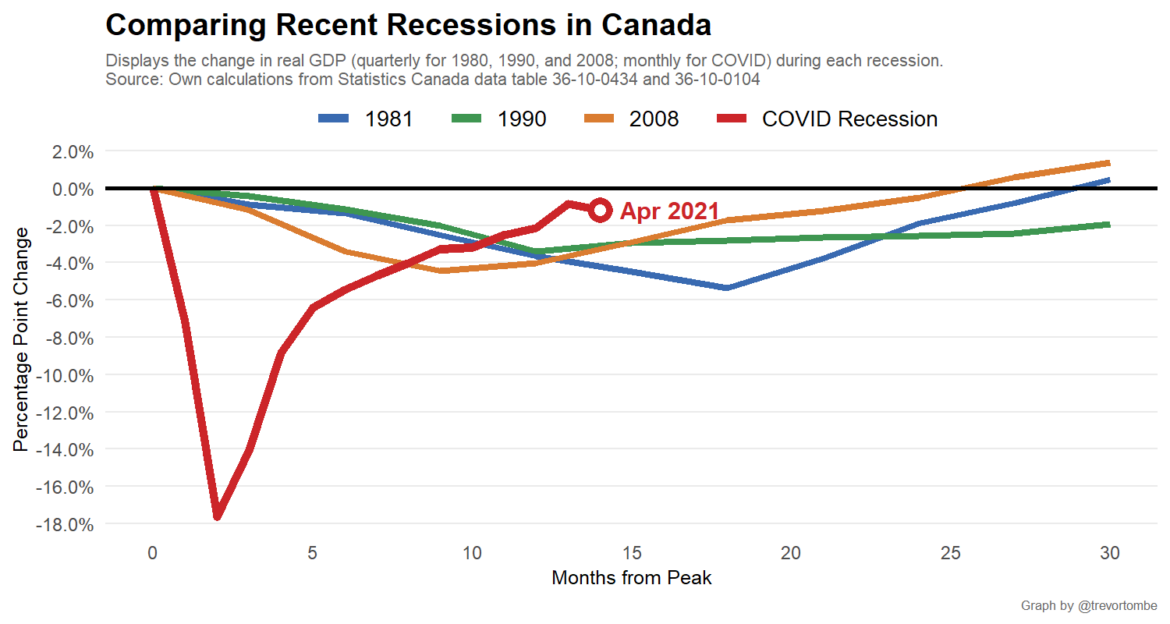

The latest aggregate economic data for Canada is from March. Though a few months old now, Canada’s economy was nearly back to its pre-COVID levels even then. This is a significantly faster recovery than many expected during the early phases of the pandemic and faster than prior recessions in Canada.

This is not to say the recovery was easy. Hard work by individuals, by families, by businesses, and by public servants and government leaders across the country allowed Canada to almost fully overcome this incredible challenge. Nor is it to say there isn’t much left to do, especially when it comes to increasing employment to pre-pandemic levels.

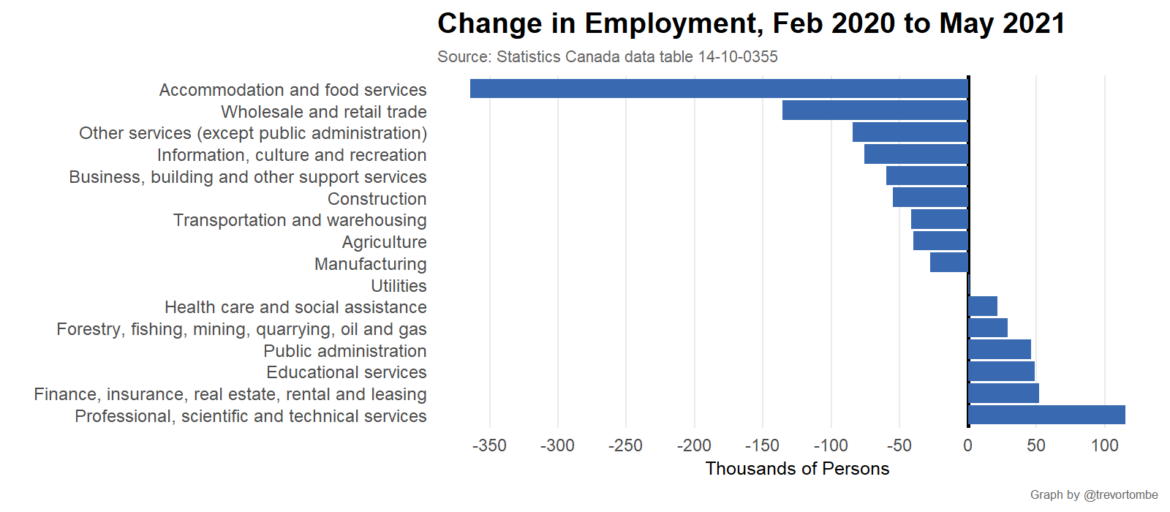

The latest jobs report shows Canada’s employment rate (that is, the number of people with jobs as a share of the population aged 15 and above) at 59.4 per cent. That’s roughly two points below where it was — or roughly 500,000 jobs.

But if employment in just three sectors (accommodation and food services, retail trade, culture and recreation) returns to pre-pandemic levels, then so too will Canada’s total employment. These are sectors particularly disrupted from COVID but primed for a strong rebound as reopenings proceed and public health conditions continue to improve. All without stimulus.

In an important sense, the largest factors holding economic activity back are transitory. There are “supply side” constraints on activity, from public health restrictions and the required changes in business operations. And there are “demand side” constraints, from individuals sensibly changing their behaviour in the presence of a highly transmissible virus. As public health improves, each of these factors will fade — and potentially very quickly.

A better debate about government spending

This does not mean the government should scrap its spending plans.

Many of the measures in the budget should best be seen as separate from broader economic recovery initiatives. Affordable housing and homelessness supports ($3.1 billion over five years), increased R&D support ($6.1 billion), additional public transit funding ($5.9 billion), increasing certain elderly benefits ($10.7 billion), boosting funding for Indigenous communities ($15.2 billion; mainly health and infrastructure measures), enlarging the Canada Workers Benefit ($8.9 billion), and the biggest ticket item of all, establishing national childcare and early-learning ($29.8 billion).

Not all COVID-related scars will be healed when the economy recovers. And some of these programs could help and indeed may be long overdue. Many small businesses may be unable to reopen. Many families will have their ability to work disrupted, especially those with younger children. The government would be justified in arguing for planned spending initiatives on their own merits, and opponents would be justified in arguing against those merits or for alternative programs.

That’s a productive debate to be had — but one entirely separated from the merits of fiscal stimulus. Permanent areas of government program spending should ideally be financed through taxation, rather than borrowing. If the benefits exceed the costs, then the costs are worth paying.

As Canada emerges from the pandemic, one thing is increasingly clear: only months after the government revealed its fiscal plans, pitched as fiscal stimulus, the macroeconomic case for higher spending is significantly weaker. Stimulus may no longer be needed.

And whether one supports this spending or not, that’s a good thing.

Recommended for You

Need to Know: Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ marks the end of the global free trade era

Trevor Tombe: There’s a lot we can learn from Canada’s last trade-war election

‘It’s the destruction of American leadership’: David Frum breaks down Donald Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs plan

‘It doesn’t put out the fire, it makes it worse’: Ian Lee on why retaliatory tariffs aren’t the answer to Canada’s trade war woes