Erin O’Toole justified his pivot of the Conservative Party into a more progressive “Red Tory” party, believing that winning over non-traditional Conservative voters is the most effective way to grow the Conservative tent and win government.

However, the 2021 election is now over, and the Parliament of 2021 looks very similar to the Parliament of 2019. Erin O’Toole’s pivot was therefore insufficient to deliver the votes required to win an election. However, Conservatives eager to blame the loss on a so-called “leftward shift” are missing the mark — the Conservative party’s shift did deliver working-class votes. What it failed to do was undermine the Liberal Party’s pre-existing and growing demographic advantage.

After the 2015 defeat, the common refrain among Conservatives was that Canadians had grown tired of “Harper-style” politics and wanted a different approach.

The team behind Andrew Scheer’s campaign assumed that Canadians (particularly the coveted middle-class suburbanites) liked Harper policies but they just did not like the Harper Approach™. So, Scheer pitched himself as an affable “Harper with a smile.”

That didn’t work for Scheer and Erin O’Toole, for his part, took a different approach because his team concluded that the demographics and politics of the country had changed since the 2011 majority victory. Considering the electoral map over the past two decades, we can draw a few general rules: Liberals win in downtown cores, Tories win in rural Alberta and Saskatchewan, and the rest is up for grabs. The question is then: how can a party win ‘the rest’?

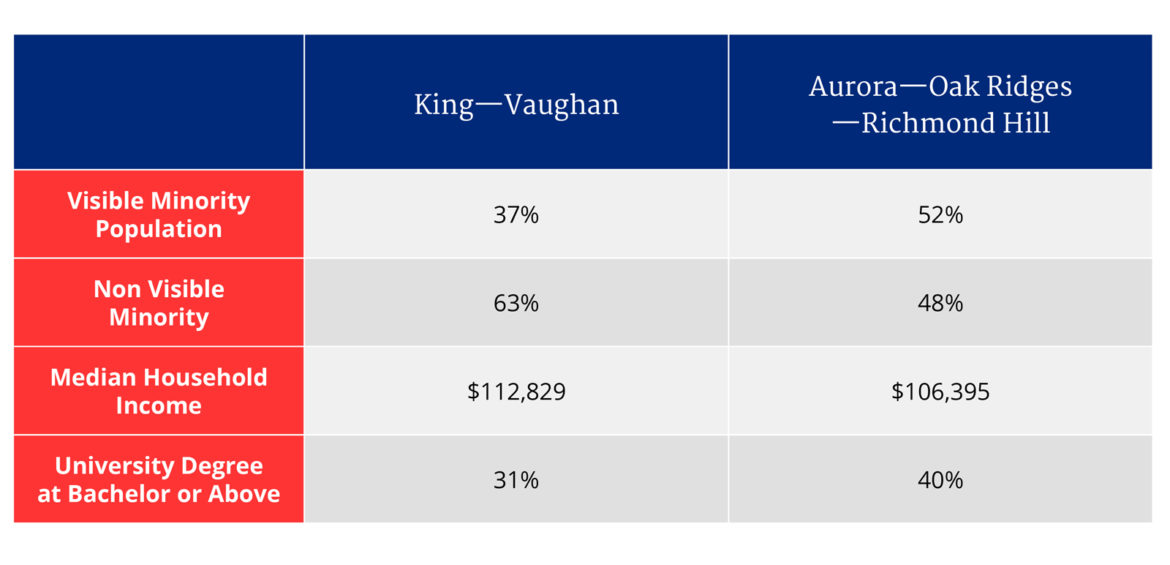

While Canada is a diverse country, the demographics of “the rest” compared to the downtown cores do bear out a few patterns, “the rest” typically is lower-income, has a lower rate of post-secondary educational attainment, and tends to be less racially diverse.

However, the suburbs of our major centres tend to have attributes of both the downtown cores and “the rest.” They have a broad range of incomes, educational attainment, and significant local variations in racial diversity as different racialized communities tend to settle in different places.

Considering recent voter patterns in the United States and the United Kingdom, it should not surprise us that much has been written about the so-called “global realignment.” White working-class voters, typically reliable voters for centre-left parties, have shifted to parties on the right side of the spectrum. It is, therefore, an easy conclusion to draw that if the Conservatives are to win, they need to align the party towards working-class voters, traditionally the domain of the Liberals and the NDP.

The intellectual underpinnings of this movement have been discussed at length by many commentators in this country, including the former prime minister whose own work expanded on David Goodhart’s work in the United Kingdom. Donald Trump won his victory in the 2016 presidential election on the backs of working-class white voters in northern, traditionally Democratic, states.

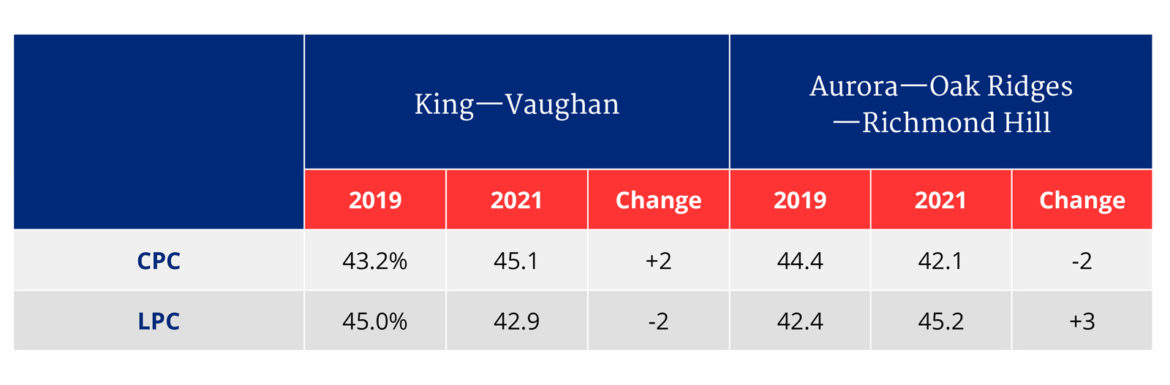

So why is it then that the Conservative Party failed to win the dramatic victories won by Boris Johnson and Donald Trump? As a case study, let us consider the neighbouring ridings of King—Vaughan and Aurora—Oak Ridges—Richmond Hill.

While the swing was not large enough to discount local factors completely, a few interesting observations jump out to me while examining the census profile of King—Vaughan and Aurora—Oak Ridges—Richmond Hill.

Despite having similar incomes in each electoral district, the better educated and less white district of Aurora—Oak Ridges—Richmond Hill swung towards the Liberals, whereas King—Vaughan swung towards the Conservatives.

Outside of the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), two other ridings held by the Liberals in 2019 swung from the Liberals to the Conservatives in Ontario: Bay of Quinte and Peterborough—Kawartha. Notable for their comparatively whiter, more working-class demographics as opposed to GTA ridings.

In Northern Ontario, despite failing to flip seats, the Conservatives maintained or improved their performance in working-class districts: +9 percent in Kenora, +5 percent in Sault Ste. Marie, +7 percent in Sudbury, and +6 percent in Nickel Belt. In Hamilton, traditionally a blue-collar town, the Conservatives improved in all seats except for Hamilton Mountain.

I would be remiss if I failed to mention the NDP’s performance in the GTA as their presence reveals important dynamics. For example, the City of Brampton, located within the GTA, is majority-minority. In the 2016 Census, 73 percent of Brampton residents indicated that they were a visible minority. Federally, Brampton is represented by five seats. Compared to 2019, the NDP declined on average –4 percent per riding. The Conservatives improved in Brampton on average +4 percent per riding. The Liberals, for their part, improved on average +3 percent.

These results suggest that while the Conservative successfully pivoted to working-class voters, the pivot was effectively checked by Liberal gains among visible minority communities, particularly in the suburbs. The 2011 Harper campaign and the 2018 Ford Campaign both were won by sweeping the suburbs around Toronto proper. Those seats are distinct precisely because of their high concentration of visible minorities.

Between the 2011 and 2015 elections, 30 additional seats were added to the House of Commons. Fifteen of those seats were in Ontario and, of the 15 seats added, most of those seats were in the Toronto suburbs. Heading into the 2015 election, almost all of the new Conservative seats were notionally Conservative-held.

The 2015 election reversed all those previous actual and notional gains in the GTA. Most commentators pointed to the niqab ban, the barbaric cultural practices hotline, and revocation of citizenship for dual citizens convicted of certain offences as playing a role in eroding trust between Conservatives and visible minority communities. In the 2021 Election, Conservative support among the Chinese communities plunged, potentially because of a reaction to the party’s tough-on-China stance.

The choices made in the respective lead-ups to the 2015 and 2021 elections have resulted in a Conservative party that is whiter and more working-class than the Conservative Party of 2011. While this was enough to deny the Liberals a majority in 2021, the chances of winning government on the backs of white working-class voters will become even smaller in the future. With the completion of the 2021 census, even more seats will be added to the Toronto suburbs, given that the Toronto suburbs are Canada’s fastest-growing areas.

Whether the Conservatives maintain their working-class pivot, their policy choices, direction, and outreach efforts need to include visible minority communities. A failure to do so will only make overcoming the Liberal’s current demographic advantage even more difficult.

Recommended for You

Alfred Apps: Wake up, Canada: Just being woke isn’t good enough

Élie Cantin-Nantel: Progressive Quebec is done with multiculturalism. Here’s why

The Weekly Wrap: Between Trump’s tariffs and Canada’s weak economy, Mark Carney’s job just keeps getting harder

‘We are entering a new world’: The Roundtable on the collapse of global free trade and what Canada must do next