The National Health Expenditure Trends 2021 report from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) has just been released, and the data provides a much-awaited, macro level first look at what happened to health spending during the COVID-19 pandemic. At first glance, the numbers are what one expects—and quite sobering.

Canada is expected to spend a new record of $308 billion on health care in 2021. That is $8,019 per Canadian. It is also anticipated that health expenditure will represent 12.7 percent of Canada’s gross domestic product in 2021, following a high of 13.7 percent in 2020.

In terms of composition, hospitals (25 percent), drugs (14 percent), and physicians (13 percent) continue to account for the largest shares of health dollars (more than 50 percent of total health spending) in 2021.

A new spending category—COVID-19 Response Funding—makes its debut, and consists of the federal direct and provincial/territorial government–sector spending to combat the pandemic. This includes money for treatment costs, testing and contact tracing, vaccination, medical goods, and other related expenses, and is a separate category from the standard ones used. Overall, it constitutes 7 percent of total health spending.

As reported by the CIHI, total health spending is expected to have increased by nearly 13 percent between 2019 and 2020, a rate of increase not seen in more than 30 years and triple the growth rate experienced from 2015 to 2019 (which was steady at approximately 4 percent per year). This historic spending increase took place alongside a contraction in the economy that was due in part to the ongoing pandemic. However, 2021 is expected to see a moderation of spending growth down to 2.2 percent as COVID-19 response support drops from $30.6 billion in 2020 to $22.8 billion in 2021, a decline of 25 percent.

While total health spending is up, it remains that the closing of outpatient departments and postponing of medical visits and procedures during the height of the pandemic meant a reduction in some aspects of health service provision and health spending. According to CIHI’s own analysis of COVID-19’s effect on hospital care services, from March to December 2020 overall surgery numbers fell 22 percent compared with the same period in 2019, a drop of 413,000 surgeries.

Indeed, once one starts to examine spending both including and excluding the COVID-19 response spending provided, as well as adjusting for inflation and population growth, the picture looks more variable depending on the categories examined and the financing sector considered. The public sector accounts for three quarters of Canadian health spending, with provincial and territorial governments alone responsible for about two-thirds of health spending in Canada. Other public sector spending accounts for about 9 percent, with the remaining 25 percent coming from private sector spending (mainly out of pocket and private insurance).

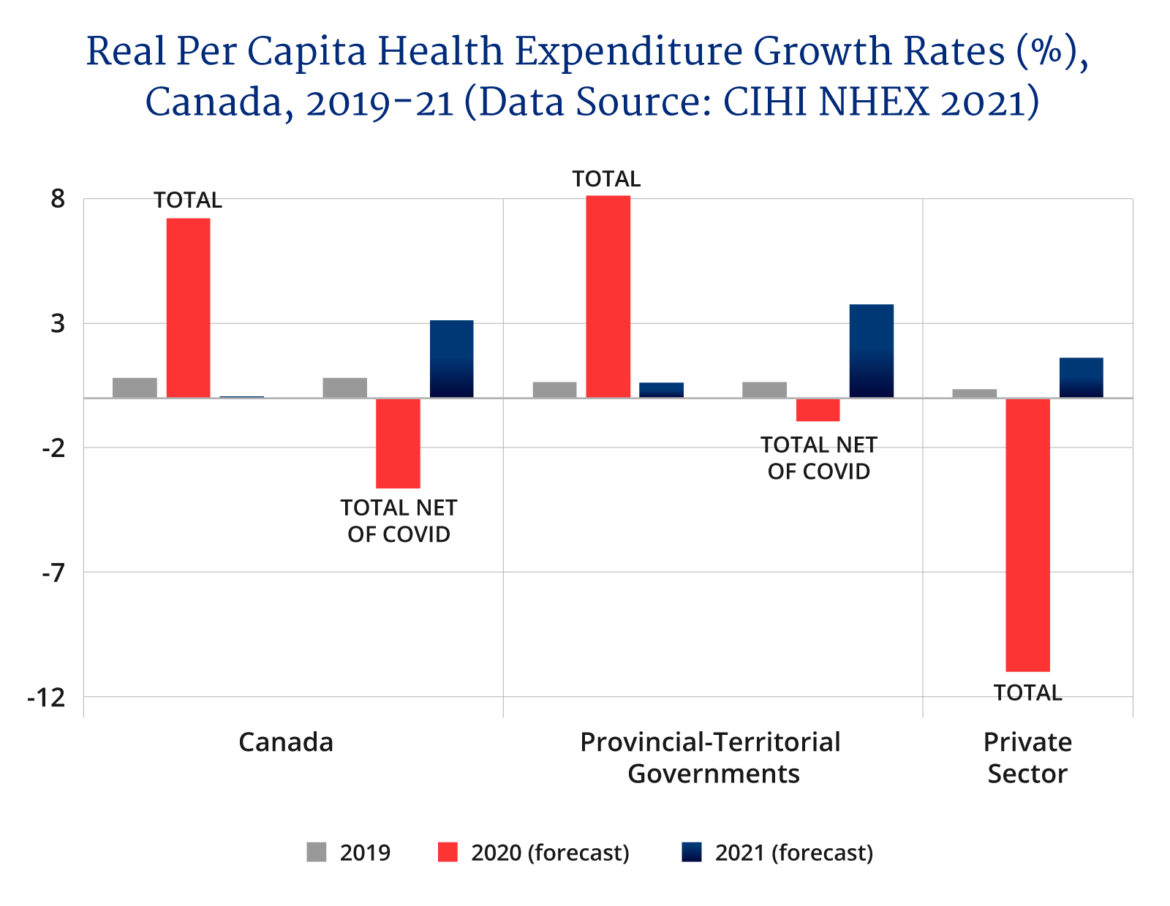

Figure 1 presents annual real per capita health expenditure growth rates for the years 2019, 2020, and 2021 (the latter two being forecasts) for total Canadian health spending (public and private sector), provincial-territorial government spending, and private sector spending calculated using the CIHI data. In 2019, real per capita total health spending in Canada grew about 1 percent and soared to 7.2 percent in 2020 but is expected to rise barely one-tenth of one percent in 2021. However, when the COVID-19 response spending is removed it turns out that real per capita health spending (net of COVID) in 2020 declined 3.6 percent but is expected to rebound by 3.1 percent in 2021.

Variable spending across the provinces

Meanwhile, when provincial-territorial governments alone are examined, their real per capita total health spending in 2020 rose 8.1 percent. However, once the COVID-19 response is factored out, their spending declined by about 1 percent, though it is also expected to rebound in 2021. Hardest hit in provincial-territorial health spending in 2020 in terms of percentage declines in real per capita spending were physicians (-5.8), other professionals (-6.1), drugs (-2.3), and hospitals (-0.5). These results are not unexpected given the decline in surgeries and physician visits brought about by the pandemic. Meanwhile, public health grew 4.1 percent, other institutions (including long-term care) grew 1.2 percent, and capital spending grew 10 percent.

Moreover, real per capita spending growth net of the COVID-19 response funding was also variable across provinces in 2020. Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta saw a decline in real per capita spending net of COVID-19 response funding. On the other hand, Ontario, British Columbia, and Nova Scotia saw small increases, with Ontario the largest at 1.2 percent.

New Brunswick, Quebec, and Alberta saw the biggest declines in real per capita health spending at -3.3, -3.5, and -3.6 percent respectively. This demonstrates that during the health system disruption of the pandemic, the decline in service provision, at least as measured by real per capita spending, was greater in some provinces relative to others.

The postponement of so many treatments and surgeris will have health consequences for years to come.

The impact of COVID-19 was exceptionally severe on elective and discretionary health expenditures as borne out by the private sector impact, driven particularly by spending on private physicians, dentists, and optometrists. Real per capita private health spending in Canada in 2020 dropped by 11 percent. It is only expected to rebound by about 1.6 percent in 2021. Real per capita private sector physician spending declined 24 percent in 2020 while that on other health professionals fell 22 percent. For hospitals this was down 13 percent, and for drug spending this was down nearly 5 percent.

Future consequences

In the end, the impact of COVID-19 on Canadian health spending was not simple. While overall spending grew dramatically in 2020 in response to the pandemic, there was a displacement effect as spending on surgeries and other treatments fell with cancellations and postponements. This hit provincial government health spending hard, but private sector spending was hit even harder. The postponement of so many treatments and surgeries will have health consequences for years to come.

In terms of the implications for future health spending, this snapshot needs to be placed in the context of the longer-term trends in health spending, which has generally grown both in terms of real per capita spending and as a share of GDP. The 2010s saw a moderation in spending growth rates which led some to conclude that the health cost curve may have finally been tamed. Part of the moderation may have been a provincial response to the end of the six percent growth rate of the federal health transfer in 2017 and the new formula restricting the growth of federal transfers to GDP growth subject to a minimum of three percent.

However, there was also a moderation of cost drivers during this period, such as technological extension and the onset of new pharmaceutical products, and that may be coming to an end given that the pandemic has been a catalyst for pharmaceutical development. Combined with the concerns about health human services shortages in health care and the need to reinvest, the pandemic may indeed be the trigger event that starts a new cycle of rising health expenditures.

Recommended for You

DeepDive: Under pressure: How immigration is becoming a political fault line in Canada

Andrew Leslie: A bold step forward for Canada’s defence

Renze Nauta: Nearly seven million Canadians are in the working class. Their growing struggles deserve the spotlight

Sean Speer and Taylor Jackson: Slow economic growth is the biggest challenge facing Canada. The Hunter Prize for Public Policy is here to solve it