Perhaps those who read Professor Zhang Weiwei’s remarks in a recent Hub Dialogue were left with an impression that as an erudite and sophisticated polymath, Zhang commands a wide and deep array of intellectual insight on Chinese and Western history, culture, economics, political theory, and more.

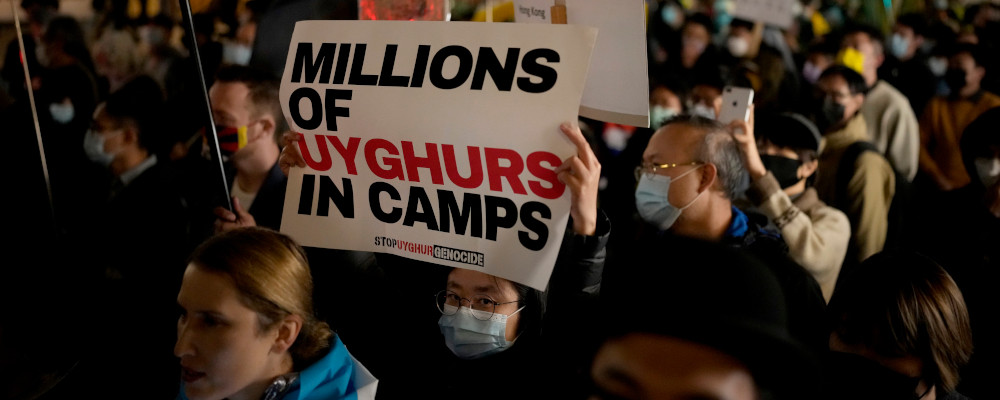

In fact, Zhang Weiwei also has a consistent record of dissembling in support of the Chinese Communist Party’s official propaganda line on Hong Kong and Xinjiang to foreigners who should know better. He falsely alleged to the BBC last year that opposition to the National Security Law in Hong Kong was the fault of “certain political forces in the West.” In the same interview, he made the chilling and horrifying assertion that criticism of Beijing’s genocidal policies toward the Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims made him “laugh my head off,” adding that “Xinjiang attracted 200 million and even more tourists [in 2019]. And for three years no terrorism. So this is a remarkable achievement.”

In this most recent interview, true to form, he told a number of whoppers knowing full well that he would not be challenged.

First, let’s take his claims about income inequality leading to the wealthy having more political influence in the U.S. than in China. This is certainly not borne out by the facts. Beijing is officially the billionaire capital of the world for the sixth year running with 145 billionaires living in the city. Shanghai also overtook New York to claim second place with 113 billionaires. According to the Hurun Report, a Shanghai-based wealth tracker, the top-20 richest Chinese businessmen delegates at the recent annual meeting of China’s rubber-stamp parliament and its advisory body in Beijing are worth US$534 billion collectively.

It should come as no surprise then that the level of income inequality in China today is very high. According to the official data, China’s Gini coefficient (a measure of inequality that ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 representing complete equality and 1 representing complete inequality) is around 0.47. By comparison, the US’s Gini coefficient is around 0.41. At the same time, some 40 percent of China’s population lives off a monthly income of 154 dollars or less. Commendable progress has been made toward reducing extreme poverty in China, but it is far more modest than Zhang Weiwei would have you believe.

Second, the claim that China’s strong man Communist Party General-Secretary Xi Jinping “started from very a humble background” is similarly absurd. Xi rose to power based on his “red nobility” birth. His father, Xi Zhongxun, was Head of the Ministry of Propaganda of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee and rose to be Secretary-General of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Humble beginnings they weren’t. So much for the nonsense Zhang expounds on China as a meritocracy.

Income inequality in China today is very high.

One of the most outrageous sections is Zhang Weiwei’s unsolicited false narrative on Xi Jinping’s handling of the outbreak of COVID-19, which is worth quoting in full:

“When COVID-19 broke out in Wuhan, and when Chinese scientists and doctors said it’s highly contagious, President Xi Jinping made a decision: the city of Wuhan must be blocked. That’s the only way. On January 23, 2020, it was blocked. No one knew the consequences, but from the consultations with Chinese medical doctors and scientists, he saw that as the only solution, because it was on the eve of the Chinese Spring Festival—which was the following the day—which is like your Christmas. If that step was not taken, COVID-19 would have spread across China. Instead it was confined in Wuhan and Hubei province.”

But of course, as we know only too well, the doctors in Wuhan tried desperately to warn about the human-to-human transmission of the newly discovered SARS-like pneumonia but were hauled in by the police and forced to recant. One of them, Dr. Li Wenliang, tragically perished due to COVID-19, at his end deeply troubled and angry over the mismanagement by the central leadership in Beijing. The fact is that closing off exit from Wuhan just the day before the Lunar New Year holiday was far too late to prevent Wuhan’s vast cohort of millions of rural migrant workers from making their annual return to their families for the Festival.

The resulting death toll from the spread of the virus all over China’s countryside was horrendous. And due to the regime keeping the truth about human-to-human transmission from the world, by the time we closed our borders the disease was well established abroad. Millions have died from the disease. Even still, the PRC still refuses to allow access to the relevant data or free access to sites of interest in Hubei and Yunnan for a neutral international investigation of the origins of the pandemic and the lessons that the world can draw from it.

But most damaging is Zhang’s deliberate attempts to obfuscate the nature of authoritarianism in the Chinese Communist Party regime. He points to three reasons why describing China as authoritarian is lazy. First, the Chinese Communist Party appears to enjoy broad support reflected in public opinion polls. Second, the CCP’s decision-making and leadership have effected positive change in China. Lastly, the term “authoritarian” is imprecise because it describes too many regimes and individuals.

But Zhang fails to define what an authoritarian is. All of his obfuscations are frankly irrelevant and downright disingenuous beyond that. Authoritarianism simply refers to a regime typology with a similar set of characteristics. Chief among them is undemocratic political legitimation, in which political power does not come from the people through fair and freely contested elections. Other elements include concentrated power within a single party apparatus or executive, limited political liberties, limited adherence to human rights norms, and a lack of independence for other branches of government. In all of these cases, China rises clearly to the threshold of what political scientists like Zhang readily understand as authoritarian.

Despite differences between Mao Zedong or Deng Xiaoping or Xi Jinping, for instance, they share a crucial similarity: all political power in China is moderated, controlled, or guided by the CCP. Each subsequent leader in China further reinforces the essential fact that the regime is the Party, that the Party has full and uncontestable control, and that the Party will be led by one of its own chosen sons.

All political power in China is moderated, controlled, or guided by the CCP.

In his original remarks, Zhang also claimed during the event that China is uniquely iterative in its process for developing national policy, but this is not true. No matter how many consultations feed into China’s Five Year Plans, they always and by necessity reflect the CCP’s own priorities; political power flows uniformly from the top down, not from the bottom up as is the case in democracies. And to that end, democracies also engage in iterative and massive consultations on policy, such as when it comes to budgets. But they do so while being kept honest and pressured by robust civil society, media, loyal opposition, and regular elections.

By contrast, the ultimate purpose of the Chinese Communist Party’s policies today is to keep Xi Jinping’s absolute leadership unchallenged. No matter how broad the consultation, this is the overriding objective.

In terms of the obfuscations themselves, this is where Zhang’s remarks become both interesting and more troubling. If it is true that the CCP enjoys such broad-based support as Zhang claims, why can’t the Party allow for fair and free elections? Presumably, in his view, they are doing such a good job that they would win every election by a landslide.

But Zhang knows the score. The CCP’s supposed popularity is premised on a lack of alternative, a distressing reality that many Chinese people themselves acknowledge. We can see this in its purest form when considering China’s Communist Party’s brutal history of suppression—from the 1950s Hundred Flowers Campaign leading to the first massive, major purge of China’s “rightist” intellectuals, the 1960s and 70s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution violence in which over 700,000 died, the Tiananmen Square Massacre, to the violent suppression of the recent protests in Hong Kong.

Zhang can spare us all his clever rhetoric on the CCP’s supposed “support” that it enjoys; that support is ankle-deep, and the regime knows it. That is why it comes beneath the force of leather jackboots and tank treads, at the point of bayonets and rifles, and through the lens of surveillance cameras and facial recognition software. China, more than many modern states, is a clear authoritarian country in every sense of the word.

Zhang also argues that a conflict-minded approach of states historically is a by-product of a Western mindset and that China is peace-loving. Not only is this claim nakedly ahistorical (China’s history is replete with exactly the same kinds of bitter wars that define countries like those in Europe, although often at a larger scale) but it is also false given what we see today from China.

The reader should not let Zhang’s vagaries distract them from the fact the PRC invaded and conquered Tibet, is engaged in border aggression against India in the Himalayas, has flown hundreds of incursions into Taiwan’s Air Defence Identification Zone over the last year, is actively running grey zone aggression campaigns in the South and East China Seas, has constructed an array of militarized maritime islets to bolster territorial claims in contravention of international law, and is running what is best described as a genocide against Uyghurs in Xinjiang on the grounds of “security.” This is to say nothing of the bellicose posturing and rhetoric that defines Xi’s “wolf warrior” diplomacy.

It goes without saying, but these are not the actions of a peace-loving nation.

So then why would Zhang, a professor of repute who almost certainly knows better, engage in such falsehoods? The answer is as simple as it is disappointing: he wants to trick his audience, assuming that his listeners and readers lack the ability to think critically about his statements. He was selling a curated propaganda message, an arrogant and self-assured diatribe that is comfortable to China’s elites and opaque to the uninitiated.

We should not allow ourselves to be fooled by Zhang and his fellow smug and wealthy CCP elites. They thrive in collective ignorance, which is why compelled ignorance or apathy is so eagerly imposed from the regime onto the Chinese people through censorship and control of the media and other institutions. Similarly, for us, Zhang is the frontman for a con that plays on our naïve goodwill, whereby he shared nothing less than a collection of well-rehearsed lies pre-approved by his Chinese Communist handlers.

Recommended for You

‘Another round of trying to pull capital from Canada’: The Roundtable on Trump’s latest tariff salvo

‘We knew something was coming’: Joseph Steinberg on how Trump is ramping up his latest tariff threats against Canada

Rudyard Griffiths and Sean Speer: Canada’s high-stakes standoff with Trump

‘It’s not yeehaw, it’s yahoo’: Tim Hudak and Anila Umar on why the Calgary Stampede is the ultimate political and cultural equalizer