“He had blond hair—straight and fine—with a fresh boyish complexion. Medium height, and inclined to be plump, with a somewhat rolling gait,” said Hammy Gray’s squadron commander on HMS Formidable. “He was tremendously warm-hearted, always cheerful and even-tempered—rather easy going…modest….He liked to tell us stories of hometown life in Nelson B.C. in his mild British Columbian accent,” the officer continued, “and was unmercifully ribbed about that hick town in the west.”

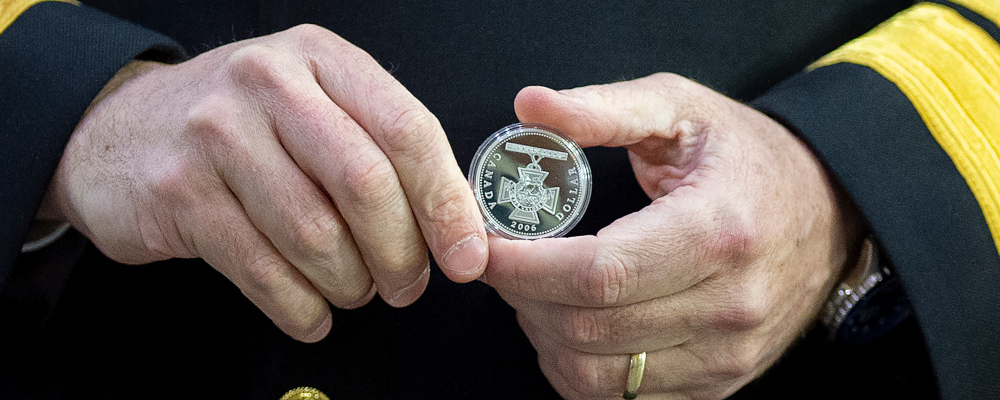

Somehow that doesn’t sound like the usual description of a hero, but Lieutenant Robert Hampton Gray, Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve, would receive the Distinguished Service Cross and the Victoria Cross posthumously for his actions during the final stages of the war in the Pacific in the summer of 1945.

Robert Hampton Gray was born in Trail, B.C. in 1917—his father was a Boer War veteran and jeweller—and grew up in Nelson. After high school, he attended the University of Alberta for one year, then transferred to the University of British Columbia. He had intended to go to McGill to get a medical degree but instead joined the Navy in the summer of 1940. He did his basic training at HMCS Stadacona in Halifax, then applied for officer and pilot training. Many applied for the first, fewer for the second, but Gray was chosen for both and proceeded to England where he was commissioned as a sub-lieutenant.

Gray then returned to Canada for flying training under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in Kingston, Ontario, returned to Britain, and then was posted to Nairobi, Kenya. There he spent most of two years as a shore-based naval pilot flying Hawker Hurricanes but with some time flying off the aircraft carrier Illustrious. His brother, flying with the Royal Canadian Air Force, was killed on operations during Gray’s African posting.

Now a lieutenant, Gray received a billet on HMS Formidable, another Royal Navy carrier, and in August 1944 played a prominent part in two attacks on the German battleship Tirpitz that was sheltering in a Norwegian fjord. The battleship was not sunk during these raids (it was in November 1944), but Gray’s courage and skill in flying his fast, well-armed fighter-bomber, the F4U Corsair, “right down the barrels” of the guns of the German destroyers protecting the Tirpitz was noted, and he was twice Mentioned in dispatches. In April 1945, Formidable joined the British Pacific Fleet as the Allies closed in on Japan, attacking shipping and shore installations.

Japan was in dire straits by the summer of 1945, its cities fire-bombed, its merchant fleet all but destroyed. There was no sign of surrender, however, and the United States and its British Commonwealth allies, including Canada, were planning a seaborne invasion that all feared would meet the same fanatical resistance the Americans had faced for almost three months at Okinawa. Japanese kamikaze pilots were still attacking Allied vessels and their airfields were prime targets. In these circumstances, the pressure on the leadership in Tokyo had to be maintained, and on July 18, 24, and 28 Gray led his flight of six Corsairs in attacks on airfields and shore installations around Japan’s Inland Sea. Once again, his remarkable bravery was noted and Admiral Sir Philip Vian, commanding the British Pacific Fleet, recommended him for an immediate award of the Distinguished Service Cross, a high decoration.

Hiroshima was struck by the atomic bomb on August 6 and, while no one in the Fleet knew in detail of its effects, it was clear that this weapon of enormous power was going to shake the Japanese leadership and that the end of the war was drawing near. Aircrew on Formidable, as Gray’s squadron leader recalled, were told “to take it easy” on August 9 and avoid unnecessary risks as they again set off to strafe airfields. Neither Gray nor his mates knew that Nagasaki had been levelled that day by the second atomic bomb.

The chosen route took Gray’s flight over Onagawa Bay on Honshu where five Imperial Japanese Navy ships were at anchor. As the citation of Gray’s Victoria Cross, announced in November 1945, “the fliers…dived in to attack. Furious fire was opened on the aircraft from army batteries on the ground and from warships in the Bay. Lieut. Gray selected for his target an enemy destroyer. He swept in oblivious of the concentrated fire and made straight for his target. His aircraft was hit and hit again, but he kept on. As he came close to the destroyer his plane caught fire but he pressed to within fifty feet of the Japanese ship and let go his bombs. He scored at least one direct hit, possibly more. The destroyer sank almost immediately. Lieutenant Gray did not return,” the citation ended. “He had given his life at the very end of his fearless bombing run.”Robert Gray Citation https://forvalour.ca/gray/citation/

The historian of the Royal Navy’s operations in the Pacific, John Winton, wrote that “Gray’s VC was in a sense the saddest and certainly one of the least-known of the war. The war was so nearly over; the cause for which he gave his life was already won.”The Victoria Cross at Sea: The Sailors, Marines and Airmen Awarded Britain’s Highest Honour https://www.scribd.com/book/444693220/The-Victoria-Cross-at-Sea-The-Sailors-Marines-and-Airmen-Awarded-Britain-s-Highest-Honour Japan capitulated on August 15. Gray was very likely the last Canadian serviceman killed in action in the Second World War, and his Victoria Cross was the only one awarded to a member of the RCN in the 1939-45 war.Second World War Victoria Cross Recipients https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/classroom/fact-sheets/vcwinner

Gray is commemorated by one of the fourteen statues and busts on The Valiants Memorial near Confederation Square in Ottawa.“The Valiants Memorial, located in downtown Ottawa, is a collection of nine busts and five statues depicting individuals who have played a role in major conflicts throughout our history. It also includes a bronze wall inscription that reads, “No day will ever erase you from the memory of time”, which is from The Aeneid by Virgil.

The monument pays tribute to the people who have served this country in times of war and the contribution they have made in building our nation. These 14 men and women were chosen for their heroism, and because they represent critical moments in Canada’s military history.” https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/art-monuments/monuments/valiants.html

Most Canadian pass it by and few know anything of Gray’s courage. They should know more. He deserves to be remembered as the Canadian hero he was.

Recommended for You

Howard Anglin: Lament for a Lament

‘A place where anybody, from anywhere, can do anything’: The Hub celebrates Canada Day

‘Putin has no intention of stopping this war’: Sir Bill Browder on three years of war in Ukraine and how Russia is evading sanctions

Ian Holloway: The Supreme Court is ditching its iconic red robes. Yes, it matters