A recent piece in The Hub by Sean Speer identifies what at first glance is a puzzling (and to some concerning) development: public-sector employment accounts for nearly 85 percent of the total employment growth in Canada since February 2020.

Instead of an L-shaped or V-shaped recovery, he writes, this G-shaped (government-centric) one “paints a different picture of the labour market’s recovery than is commonly understood.”

It is a very well-researched piece and written with skill and clarity. And as Speer does all too well, he raises important questions about difficult political dynamics that may result. If you haven’t read it yet, you should.

But I have a slightly different perspective.

Using the detailed Statistics Canada microdata on labour market conditions, I hope to shed more light on what’s behind the large growth in public-sector employment.

I’ll show that much of the increase is in areas where the “takers” versus “makers” distinction is particularly problematic. And the data reveals an even starker pattern: a massive gulf between employment growth for workers with higher education and those without. This is not only itself concerning but, it turns out, may account for much of the public-sector growth. I’ll explain.

The data

Statistics Canada makes available a wealth of labour market information to Canadians each month (see here). But there is another source that, while publicly available, is much more difficult to access and to work with: the raw microdata. But it reveals a lot.

First, who are these newly hired public-sector workers? I find the increase is mostly accounted for by young workers (56 percent are under 40) in professional and technical occupations (62 percent) who have a post-secondary certificate or degree (82 percent).

In short, they’re young, early career, and highly-educated individuals. And mostly front-line. Only 7 percent of the increase is among those in middle or senior management.

They also largely work in the health and education sectors (nearly 60 percent). Growth in the health sector is, of course, not surprising. It is also likely to continue long past COVID is behind us as our populations age.

Even those classified as working within the “public administration” sector (32 percent) may not align very well with some intuitions. Only 12 percent are in Ottawa, for example, and there are over 12,000 new construction and trades workers and another nearly 10,000 new police and other front-line public protection occupations included in this category.

And, finally, a large share of the increased public-sector employment may be temporary. I find well over one-third of the increase is by those hired on temporary or seasonal contracts. This compared to the 9 percent of private employees overall who are.

Takers versus makers?

Public-sector employment is not in and of itself a sign that a job is a drain on economic activity; often, quite the opposite. Producers of human capital, producers of health and wellness, producers of physical capital and infrastructure, producers of public safety, and so on, all add to productivity. These workers are clearly “makers”.

Instead of looking at public versus private as a guide, it may be better to ask whether the benefits of a particular job outweigh its costs. Some jobs in the private sector should not exist. Some jobs in the public sector should not exist either.

All parties want to see higher public-sector employment in some areas and lower in others.

Consider an example from a right-leaning government in Alberta, which increased government hiring in certain energy-focused public relations activities. This is in reference to the newly-created Canadian Energy Centre, sometimes referred to as the energy “war room”. The government, some argue, is better at promoting the interests of the energy industry than the energy industry itself.

To be sure, the market has a natural (and usually well functioning) mechanism to destroy inefficient jobs while creating others: profits and losses. This natural pressure to employ individuals only where benefits exceed costs operates with much less efficiency in the public sector.

Governments can and should review programs continuously—and some governments are more dedicated to this important task than others. They should also ensure compensation and work arrangements are appropriate.

And, to be absolutely clear, we shouldn’t shy away from broader conversations about where public activities are warranted and where they are not. Exploring the pros and cons of additional private provision within our provincial health systems, for example, is warranted.

But there’s another related development in Canada’s economic recovery that may be driving the public-sector growth, and one that should raise more important concerns.

An E-shaped recovery?

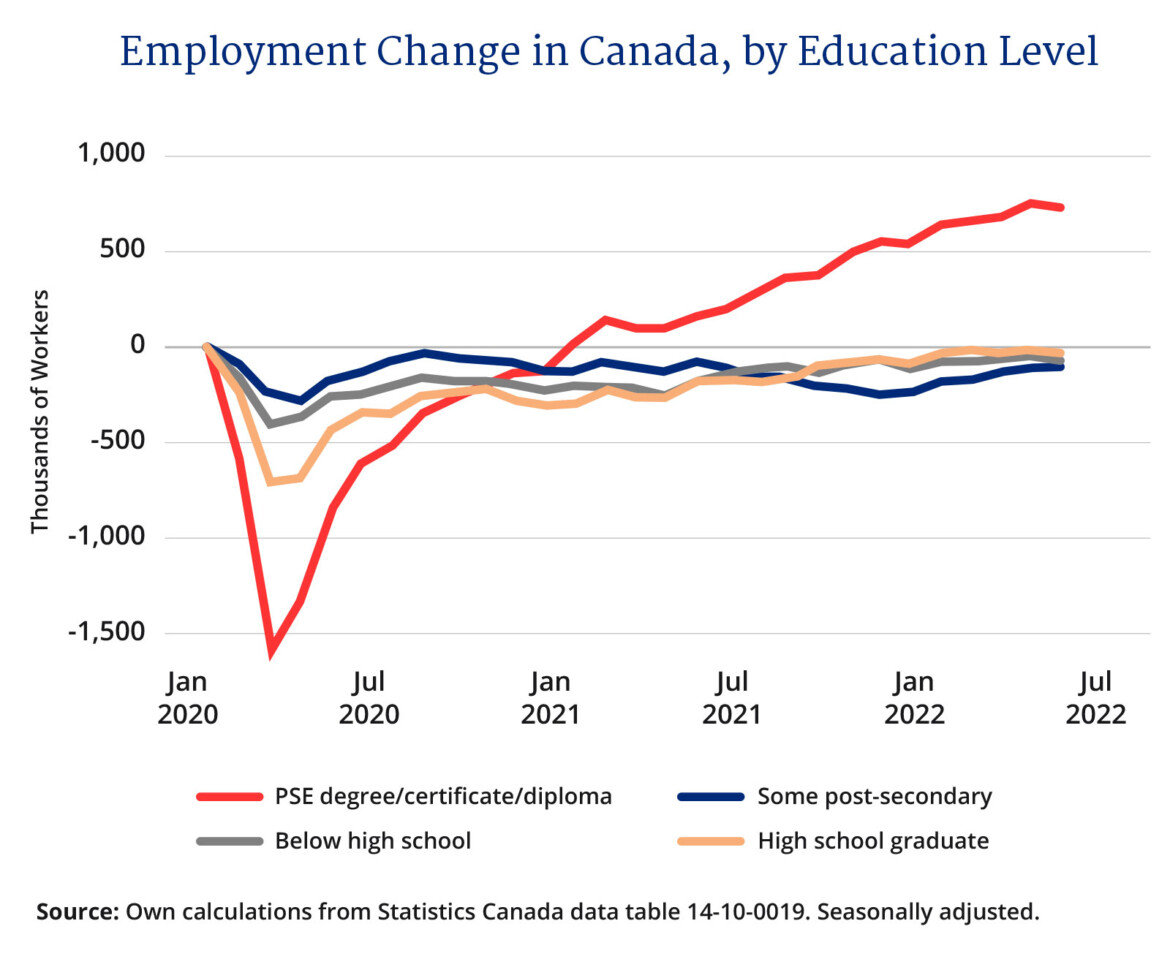

Even without the detailed microdata, one stark fact is clear in Canada’s recovery: those with higher levels of education have fared best of all.

This reveals the entire employment increase since February 2020 may be due to workers with higher levels of education. An E-shaped recovery, perhaps?

This is true in both the public and the private sectors. Of the increase in private employment between February 2020 and June 2022, I estimate fully 79 percent are accounted for by those with a post-secondary certificate or degree. That’s a similar proportion to the 82 percent among public-sector workers. These shares are not seasonally adjusted like the data in the figure.

Some occupations require postsecondary credentials more than others, of course, and some occupations are disproportionately found within the public sector. What’s interesting is that there is a strong correlation between these two. Across the 40 occupations tracked by the labour force survey data, the correlation coefficient between the share of each occupation’s employment accounted for by those with a post-secondary degree and the share who work in the public sector is 0.6. Occupations in nursing or education, for example, have among the highest share of employees with postsecondary credentials and are almost entirely within the public sector.

I estimate the rising overall employment for those with a postsecondary degree—combined with the fact that employment of such individuals is not evenly distributed between private and public sector occupations—accounts for more than half the total increase in public-sector employment.

There is growing evidence that differences in education levels are developing into a new political cleavage throughout the developed world. Whatever the underlying cause, the stark differences in economic outcomes experienced by individuals of different levels of education may only amplify these pressures.

To be clear, I’m not making a normative claim about the relative merits of different types of credentials or occupations. Nor do I believe governments should always and everywhere promote postsecondary education as the best route for all individuals—it is not.

But this data suggests (to me at least) that education levels and Canada’s E-shaped recovery may be both a key driver of its G-shaped one and a source of even greater concern.

Recommended for You

The Week in Polling: Most Canadians think Trump would break a trade deal; Americans say the UN does a poor job; Canadians expect economic decline into 2026

Canada’s GDP to remain sluggish as federal interest payments are projected to jump to $82.4 billion: PBO report

Theo Argitis: Mark Carney’s theory of the case

It’s tough being young and looking for work right now—especially in Alberta