Earlier this year, to mark the 40th anniversary of the patriation of the Canadian Constitution, UBC law professor Brian Bird wrote a four-part seriesThe Charter at Forty: The road to 1982 https://thehub.ca/2022-01-19/the-road-to-1982/ for The Hub tracing Canada’s constitutional history from Confederation to the present, ending with some thoughts about our constitutional future. It is an erudite and accessible journey through more than a century and a half of legal history, which I recommend to anyone interested in understanding the significance of 1982 as an inflection point in the modern history of Canada. In my own rather more polemical series, I make the case that by 1982 Pierre Trudeau’s constitutional vision, which was grounded in the Enlightenment values of liberal rationalism, was already outdated and that Canada’s new Constitution has thrived not on Trudeau’s intended terms, but as a broadly illiberal exercise of irrational judicial power. Here is part one, with the other three parts to follow each day this week.

With apologies to Virginia Woolf,The Hogarth Essays: Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown http://www.columbia.edu/~em36/MrBennettAndMrsBrown.pdf on or about June 1967, human nature changed. As with the birth of modernism observed by Woolf, “[t]he change was not sudden and definite … [b]ut a change there was, nevertheless” and “when human relations change there is at the same time a change in religion, conduct, politics, and literature.” So it was in the Summer of Love.

It was one of those moments in history when a subculture becomes a zeitgeist. The communal flophouses of San Francisco, so grimly chronicled by Joan Didion and Tom Wolfe, may have been the most unlikely place for a cultural revolution since the rat-infested cafes of Paris’s Latin Quarter, but that is where the eyes of the world alighted in 1967 and they remained there long enough to imprint permanently a psychedelic distortion of reality onto the Western consciousness.

The climax of this cultural moment was the Monterey Pop Festival, which ran from June 16-18. John Phillips wrote the flower-child anthem “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)” for the festival. The song begins with a dreamy invitation to join the “gentle people with flowers in their hair” in a summertime love-in, but then abruptly shifts to an urgently prophetic voice, proclaiming that “all across the nation…there’s a new generation with a new explanation.” The singer promises not just floral reverie but “people in motion,” a generation on the march.

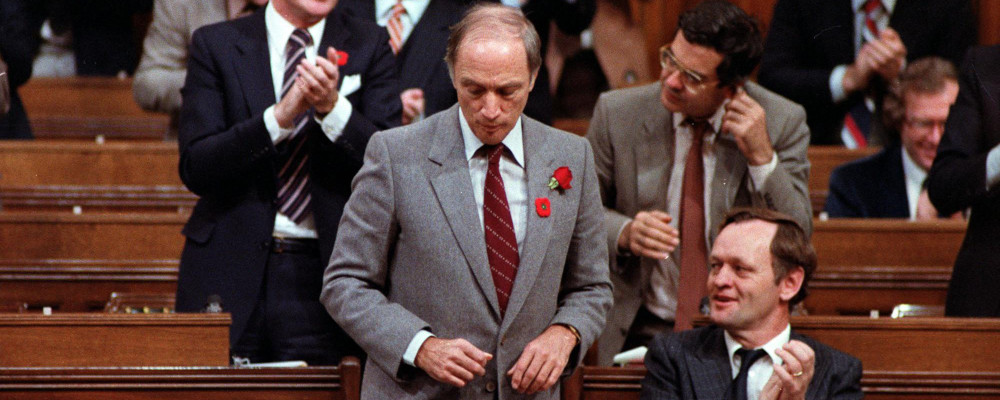

Almost exactly one year later, on June 25, 1968, Pierre Trudeau became Prime Minister of Canada. In the Canadian mythopoetic imagination, the two events—Trudeaumania and the 1960s counterculture—are usually linked, but with the benefit of distance we can see that Trudeau was an unlikely and unconvincing avatar of the 1960s.

Trudeau was no hippie. Like his near contemporary, John F. Kennedy (who, had he lived, would have loathed the hippies), he was a well-preserved relic of the world the young baby boomers sought to wash away in a trippy haze of peace, love, and sandalwood. He was a balding lawyer, older than most of their parents, and he wore his flowers in his tailored lapel rather than in his thinning hair. Far from being a new-age spiritualist or a cosmic thinker, he was a Catholic who believed in reason and its promise of scientific and social progress. About the only thing he had in common with the hippies was the age of his girlfriends.

The confusion, which was there from the beginning, is understandable. Because Trudeau’s liberalism shared many of the emancipatory goals of the younger generation—most obviously the overthrow of sexual mores (hippies, in the name of free love against repression; liberals in the name of reason against irrational tradition)—it was easy to see them as part of a common project. In fact, they were two branches of the Enlightenment that were diverging so rapidly that the newer one was turning back on the other, not to reinforce it but to devour it.

The hippies shone the light of Enlightenment skepticism back on its own premises and found a void at the heart of liberalism. Whether Trudeau realized it or not, by 1968 the Age of Reason had met its backlash in the Age of Aquarius and was on the way out. The tension between his faith in “La raison avant la passion”La Raison Avant La Passion 1968 https://www.aci-iac.ca/fr/livres-dart/joyce-wieland/oeuvres-phares/la-raison-avant-la-passion/ and the tuned-in and turned-on generation who believed in magic and good vibrations could be ignored as long as they were both sweeping tradition and convention before them. But the underlying philosophical divide was real. It was exposed most memorably during the FLQ crisis when Trudeau made it clear he had no time for bleeding hearts when they got in the way of his tanks.

Trudeau’s political project, which he had been developing in the pages of Cité Libre since the 1950s, could not have been more different than the consciousness-raising revolution of the 1960s dropouts. Unlike the hippies, who sought transcendence in the intentional irrationalism of mind-altering psychedelics, spiritualism, and ersatz Eastern mysticism, Trudeau still believed in objective truth knowable through reason. So much so that he worked with law professor Barry Strayer for more than a decade to develop a modern constitutionalism for Canada grounded in a belief that politics could be rationally ordered and directed under the supervision of neutral, apolitical judges.

It is hardly spoiling the end of the story to reveal that this is not what happened. With ultimate responsibility transferred a few hundred yards down Wellington Street from Parliament to the Supreme Court, the Canadian Constitution began to evolve apart from, and with only indirect influence from, the political work necessary to hold together an irrational society.

After 40 years of such hothouse evolution, Canada’s legal Constitution now resembles an exotic cultivar bred by an eccentric recluse. Like Des Esseintes’ flowers in A Rebours, the “living” Constitution often appears more artificial than alive, as befits a form of government driven by a liberal rationalism that is not naturally and organically tied in theory or practice to the social reality of custom, morality, and public expectation.

Recommended for You

‘There are consequences to this legislation’: Michael Geist on why the Canada-U.S. digital services tax dustup was a long time coming

Rudyard Griffiths and Sean Speer: The future of news in Canada: A call for rethinking public subsidies

‘You have to meet bullying with counter-bullying’: David Frum on how Canada can push back against Trump’s trade negotiation tactics

‘Our role is to ask uncomfortable questions’: The Full Press on why transgender issues are the third rail of Canadian journalism