Has Québec become the most conservative province in Canada?

“The current Québec provincial landscape is a clear demonstration that centre-right ideas are popular with Québecers,” says Carl Vallée. “People in English Canada should stop thinking about Québec as a progressive region of the country.”

The province that birthed Laurier, the Trudeau dynasty, and an expansive welfare state may, if polling is accurate, grant parties of the political Right a staggering majority of nearly 100 seats in the 125-seat National Assembly in Monday’s provincial election.

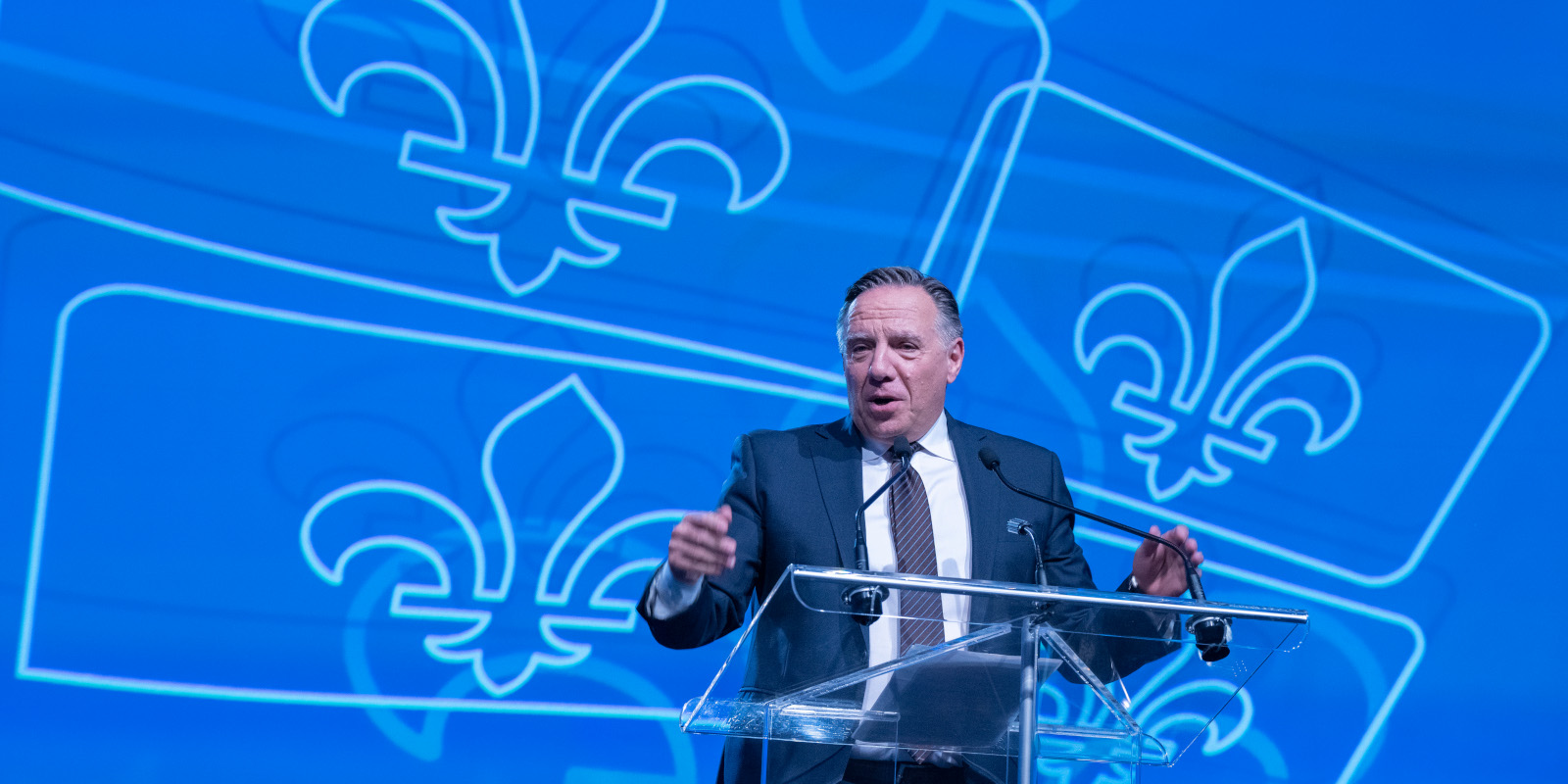

More exactly, the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ), led by Premier Francois Legault and rooted in Francophone nationalism, is set to win between 90 and over 100 seats. The Conservative Party of Québec, led by long-time conservative activist, columnist, and radio host Éric Duhaime, espouses more conventional centre-right policies and may finish second in the popular vote, though win only one or two seats.

The power of the popular vote is checked by Québec’s first-past-the-post electoral system. With five parties competing in this year’s election, vote-splitting will almost certainly help propel the CAQ to a historic majority.

Québec is often feted by English Canadians as a model of a progressive society because of the provincial government’s expansive welfare state, and so-called “Québec Inc.” model of economic development. Nonetheless, the Conservatives and CAQ are projected to win well over 50 percent of the combined provincial vote. This result would push Québec even further to the political Right after the CAQ already won an impressive 74-seat majority in the last provincial election.

Vallée, Stephen Harper’s former press secretary who also worked on Legault’s transition team in 2018, says Legault’s CAQ and the provincial Conservatives embody two different types of conservatism.

Once a cabinet minister in the Québec nationalist and separatist Parti Québecois (PQ), Legault left the party in 2009. He disavowed separatism and founded the CAQ in 2011. Striking a middle ground on the question of Quebec’s place in Canada, the CAQ promotes Francophone nationalism and greater autonomy from the federal government for Québec, while promising to never hold another referendum on independence.

According to Vallée, the CAQ adhere to a fusion of cultural conservatism and nationalism that is unique to Québec. The Conservatives, by contrast, have much more in common with right-of-centre parties outside Québec, including a policy programme of tax reductions and spending constraints.

While in power, the CAQ has worked to strengthen and protect Québec’s Francophone culture and the French language, the latter of which is declining, although it is still spoken at home by 78 percent of Québec’s population.

These measures include curbing immigration, restricting access to English primary schools, and banning visible religious symbols worn by public sector employees while working to enforce Québec’s long-standing policy of secularism. Legault has said without those measures, Québec could become like Louisiana, a U.S. state where many residents have French ancestry but have long ceased to speak French.

“The will and desire to protect our language, our culture, our heritage, celebrating our history unapologetically, all of those values are conservative in and of themselves,” says Vallée while outlining the CAQ’s priorities.

Robert Martin, a Mainstreet Research data analyst who studies Québec, says that while the CAQ is certainly a right-of-centre party, its economic policy veers towards the centre.

“A lot of the policies are conservative, but I feel like a lot of their support is driven by people who don’t necessarily view them as conservative,” says Martin. “I think a lot of people view them as moderate, and that’s why they’re pulling in those voters.”

The CAQ has cut business taxes, but also invested millions in taxpayer dollars into repairing Québec’s infrastructure and economy. Its economic policies in this year’s election include tax cuts for businesses and individuals, and promises to continue government investment in infrastructure and the economy as a whole.

The CAQ’s policy combination of cultural conservatism and economic centrism has created a powerful coalition of voters who once supported the PQ and the federalist Québec Liberal Party, independent from the federal Liberal Party since 1955.

“If you’re a Québecer, for whom Québec comes first, and you also care about the economy…you can have your cake and eat it too,” says Vallée.

Meanwhile, the Conservatives, founded in 2009, have just one seat in the National Assembly due to a defection from the CAQ. However, under Duhaime’s leadership, the party saw its support surge during the pandemic.

While not opposed to vaccines, Duhaime publicly opposed mandatory vaccines and many of Québec’s lockdown measures, calling them a violation of civil liberties and damaging to the province’s economy.

The Conservatives’ other proposals include tax cuts, smaller government, and reforms allowing for private sector participation in health-care delivery. The health-care system in Québec is one of the most chronically underperforming in Canada.

Terrence Watters, the Conservatives candidate for the Gatineau-area riding of Pontiac, points out that more than a million Québecers lack a family doctor. While debates over Québec separatism and language once dominated Québec politics, Watters says this election is about everyday issues.

“Language, don’t get me wrong, it is important,” says Watters. “For now, the most important question is bread and butter. Its inflation, its tax reduction.”

For 50 years, Vallée says Québecers largely set aside their views on issues like taxes and health-care in favour of picking sides in the political battles between the federalist Liberals and the separatist PQ.

Today, barely one in three Québecers still support independence. For now, the federalists appear to have won the sovereignty debate. However, with Québec’s old political battle lines receding, the victors have been Legault’s CAQ, not the Liberals.

“He’s reorganized Québec politics, and that’s why you can see how dominant the CAQ is,” says Vallée. “The CAQ stole or captured the nationalist identity of the PQ, and it also stole the economic identity of the Liberals.”

The Québec Liberal Party is one of Canada’s oldest political organizations. Since Confederation in 1867, the Liberals have remained relevant by always either managing to form a government or sit as the Official Opposition in the National Assembly.

In Monday’s election, the once mighty Liberals are expected to win fewer seats than at any time since the 1950s, and the smallest share of the popular vote in its history.

Traditionally, the Liberals were the choice of Francophone federalists, and nearly all Anglophones and Allophones, the latter being Québecers whose first language is neither French nor English. Anglophones and Allophones comprise roughly 20 percent of Québec’s population, and are mostly concentrated in Greater Montréal, where dozens of dense urban and suburban ridings are located.

In the mid-20th century, tensions between Québec’s large Francophone working-class and the province’s Anglophone economic elite played a major role in the growth of Francophone nationalism. Former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, himself a Québecer, has even publicly stated that all Francophones, are nationalists to varying degrees.

Former Liberal premiers like Jean Lesage and Robert Bourassa were firmly opposed to Québec becoming independent from Canada, but wove their own brand of nationalism into the party’s federalist outlook.

In 1974, Bourassa’s government passed the Official Languages Act, which made French the only official language in Québec. The PQ would later pass the Charter of the French Language, or Bill 101, in 1977, which strengthened the Act’s provisions, like punishing deli owners who put up English-only signs to advertise their products.

Back in power in 1988, Bourassa used the notwithstanding clause in the Canadian Constitution to override Supreme Court rulings that determined parts of Bill 101 were unconstitutional.

Since the rise of the pro-labour, social-democratic PQ in the 1960s, the Liberals’ big-tent federalism has been their main appeal. By the 1990s, however, the Liberals positioned themselves as the centre-right alternative for Québec voters by adopting relatively economically liberal and fiscally conservative policies.

When premiers like Ontario’s Mike Harris and British Columbia’s Gordon Campbell were spearheading economic liberalization in their provinces in the early 2000s, Jean Charest, Québec’s Liberal leader at the time, broadly followed suit. After the Liberals won the 2003 provincial election, Charest slashed spending, selectively cut taxes, and loosened the provincial labour code.

The party’s coalition included politicians like current Conservative MP Dominique Vien, who once sat in Charest’s Liberal caucus in the National Assembly. Charest himself was the runner-up in this year’s federal Conservative leadership election.

Charest governed Québec until 2012, when he was succeeded by Phillippe Couillard as party leader.

Couillard went on to win a majority in the 2014 election, during which a prominent PQ candidate declared he wanted an independent Québec. By that point, data showed just one in five Québecers favoured a referendum on independence. Observers said Québecers were tired of the sovereignty debate, and the possibility of another referendum under the PQ sank their campaign.

Continuing to govern in a fiscally conservative fashion, Couillard prioritized balanced budgets and paying off the province’s substantial debt. While the economy improved, government services that saw their budgets tightened, like the health-care system, were becoming strained.

Daniel Béland is a professor of political science at McGill University. He says that by staying the course on Charest’s economic policies, the Liberals’ austere policies eventually had consequences.

“There was still an emphasis on fiscal concerns, addressing the issue of debt in Québec,” says Béland. “He (Couillard) also triggered quite a negative reaction on the Left side of the political spectrum.”

Béland says exhaustion with austerity, especially among Francophones, contributed to the Liberals’ loss to the CAQ in the 2018 election. The Liberals won just 31 seats to the CAQ’s 74 seats, dropping nearly 17 points from their popular vote share of 42 percent in 2014, and relegating them back to the opposition benches.

Since 2020, the Liberals have been led by Dominique Anglade. Going into the 2022 provincial election, Anglade is promising billions in additional spending, and to hike taxes on the province’s highest earners to help pay for it.

The Liberal platform still promises economic development. It also heavily emphasizes themes like inclusion and investing $100 billion to achieve carbon neutrality in Québec, a sharp departure from the fiscal conservatism of Charest and Couillard.

Vallée says that under Anglade’s leadership, the Liberals have arguably become Québec’s version of Justin Trudeau’s federal Liberal Party, and most right-leaning federalists who once supported the party have abandoned it.

“It’s really embraced multiculturalism and has opposed Québec nationalism,” says Vallée. “The reason why that’s important is because there was a time in history when the Liberals embraced Québec nationalism.”

Béland says Couillard was the least nationalistic Liberal leader since World War II. Some studies do show younger Francophones value nationalism less than their parents. Nonetheless, evidence from the 2018 election suggests Francophone support for Couillard’s Liberals dropped to under 20 percent.

“What the CAQ did is that, knowing sovereignty is not going anywhere right now, but that Québec still wants a nationalist voice in Québec City…they adopted this kind of compromise,” says Béland.

According to Béland, older voters who rely more on the health-care system opted for the CAQ, who promised a more generous spending regime under the nationalist umbrella but explicitly promised to move past the independence debate.

“There was no austerity under Legault. Of course, you can say that’s partly related to the pandemic, but in fact, it started to happen before that,” says Béland. “There is a really kind of centrist approach, at least in terms of socioeconomic issues, under the Legault government.”

In 2019, the CAQ increased health-care spending by 5.5 percent, the largest increase by any provincial government. Prior, Québec was spending the lowest per person on health-care in all of Canada. By 2021, Québec had surpassed Ontario in that regard but was still one of the most frugal provinces when it came to spending per person.

Nonetheless, Béland says the CAQ’s fiscally centrist and nationalist approach has forged a powerful coalition, including many former PQ voters.

“I think that they have captured this zeitgeist, the state of mind of many older Francophones,” says Béland. “If you look at the CAQ in terms of their base, there are older Francophone voters without a university degree. That’s their main target in a way.”

In Monday’s election, the CAQ is expected to win nearly every riding outside Montréal, which are predominantly Francophone.

An Ipsos poll conducted during the 2018 election showed 73 percent of non-Francophones planned to vote Liberal, but that has likely changed under Anglade’s leadership.

Bill 96, an amendment to Bill 101 passed by the CAQ, further restricts the use of English in daily life, such as reducing the language’s prominence on bilingual signs. Most controversially, Bill 96 limits the number of non-Anglophone enrolments in government-funded English CÉGEP colleges.

In June, Anglade stated that the Liberals would alter but not repeal Bill 96 if elected. Her stance outraged Anglophones, while surveys suggested most Francophones supported the law.

Anglade herself was formerly the CAQ’s president from 2012 to 2013, before resigning due to the party’s policies on immigration. She eventually joined the Liberals and served as the minister of the economy under Couillard’s austere government. With a resumé at odds with her current progressive policy proposals, Béland says Anglade suffers from a credibility problem among voters.

“You cannot change the image of a party and its ideological direction in such a rapid way,” says Béland. “Charest is long gone, but Couillard only lost power in 2018, so it’s quite fresh in the memory of people.”

Despite Anglade’s attempts to find a middle-ground on Bill 96, recent polls suggest the Liberals will receive under 10 percent of the Francophone vote. The Liberals have also seen an exodus of Anglophone supporters, which Béland says is not helped by Anglade’s handling of Bill 96.

A September 25 Mainstreet Research poll found just 45 percent of non-Francophones intend to vote Liberals this year. The non-Francophone disenchantment with the Liberals has opened a door for Éric Duhaime’s Conservatives, which roughly 20 percent of non-Francophones plan on voting for.

“I can tell you that in past elections, many constituents voted Liberal holding their noses as that party flirted with nationalism,” says Gary Charles, the Conservatives candidate for the Montréal-area riding of Nelligan.

The Conservatives have never won a seat outright, but that may change on Monday. The party is projected to possibly win the second-largest share of the popular vote.

Watters, the Conservative candidate for Pontiac, says the Liberals were once a great party, but have shed their identity as an economically-focused party, and only now pretend to protect Anglophone interests. Duhaime has promised to repeal Bill 96 and made efforts to reach out to Anglophones during his election campaign.

“Anglophones in Québec were held hostage to the Liberals for probably the last 40 years. Now they have another option,” says Watters. “They have only one option: it is to vote for the Conservatives if you want to get rid of Bill 96.”

Vallée credits much of the Conservatives’ growth to people who suffered during the pandemic, and were attracted to Duhaime’s opposition to many of the province’s lockdown measures. Furthermore, Vallée says Duhaime may be the first politician in Québec’s history to effectively articulate libertarian ideals.

Watters says the Conservatives’ vision of lower taxes and smaller government offers a version of conservatism that differs from the CAQ, and is recognizable to right-leaning voters from the rest of Canada.

There are still similarities between the two parties’ platforms. Duhaime wants private health-care insurance providers and clinics to participate in Québec’s health-care system, while the CAQ is promising to open private medical clinics too.

However, Vallée says the Conservatives have a low ceiling in Québec. He points out that ridings with the most Conservative support tend to be CAQ strongholds. Even if the Conservatives come second in the popular vote on Monday, it will be lucky to win a single seat for that reason.

“Libertarianism in Québec has always been quite marginal,” says Vallée. “Its growth potential is quite low because those ideas are not historically rooted.”

The Conservatives are also supported by similar percentages of Francophones and non-Francophones, but Mainstreet Research also found the party was the second choice of less than 10 percent of all Québec voters. Vallée says how the CAQ governs after the election will determine if the Conservatives continue growing as a party, or if their current supporters will fall in with the CAQ.

Although a massive CAQ majority is nearly certain, Béland says the party’s coalition is more fragile than it appears. Béland says the CAQ is benefitting from unusually high vote-splitting, and that if Francophone voters begin migrating back to the Liberals and PQ in the future, the CAQ will be greatly weakened.

Béland believes the Liberals still have a future in Québec politics because their support in Montréal, although currently diminished, ensures they will always have a dozen seats. Despite their weakened popularity, the Liberals are expected to win between 10 and 25 seats due to their remaining base in Montréal, enabling them to continue as the Official Opposition.

Béland says Anglade will likely step down as leader soon after the election, putting the Liberals’ future in flux.

“The next leader might be somebody who will maybe try to push the party towards the centre-right,” says Béland. “Will the next leader be more assertive in terms of adding a more nationalistic discourse? Possibly, but they also need to find a balance in terms of keeping the Anglophones and Allophones.”

They may be hard-pressed to rebuild their base while contending with the CAQ and the Conservatives, which Watters and Charles say is here to say.

“The Conservatives will become a permanent political force. Future elections will be won or lost on everyday issues and not on a promise to keep or change Québec’s status in Canada,” says Charles.

What is certain is that conservative ideas, unique to Québec or not, have guided the province’s government for the last four years. Barring a complete collapse of support for the CAQ over the weekend, those principles will almost certainly guide it for another four after Monday night.

Recommended for You

‘We’ve got a lot of vulnerabilities’: The risks involved with pursuing a ‘strategic partnership’ with China

Alberta and the notwithstanding clause: Why the province just used it, and why it was logical to do so

Canada is quickly becoming a country where your social media posts could land you in jail

Is Alberta justified in using the notwithstanding clause to legislate teachers back to work?