If you’ve seen the term “greedflation” used in news articles or by political figures lately, then you’re aware that many are concerned about rising profits as a key driver of inflation.

Such concern is not unwarranted. Profits in Canada are indeed at record highs. In the second quarter this year—that is, from May to June, which is the most recent data—overall corporate profits (before taxes) exceeded $153 billion. That is over 21 percent higher than the same period last year. And in the non-financial sector, which accounts for almost the entire increase, profits are up over 30 percent.

Some look at this and draw a simple conclusion: rising prices and inflation are made worse by corporate greed. The NDP leader Jagmeet Singh even calls for an investigation into grocery store chains, directly connecting rising profits in that sector to inflation.

“Corporate greed is a significant driver of inflation,” the party recently claimed.

A careful look at the data, however, reveals a very different story—as it often does.

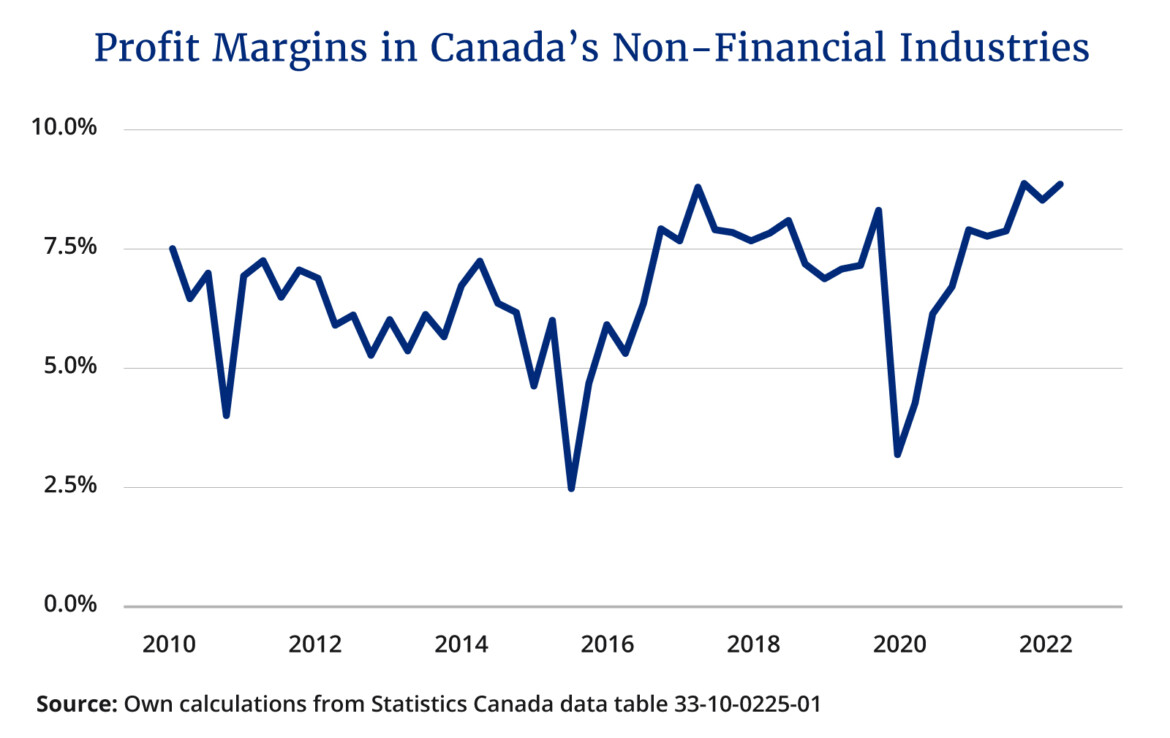

It is of course true that firms exercising more market power could in principle fuel both inflation and profits. And profit margins (profits as a share of total revenue) in Canada’s non-financial sector are up.

In the second quarter of 2021, for example, average profits were 7.6 percent of total revenue. In the second quarter of this year, profit margins increased to just under 9 percent.

This is a large increase—with margins in the second quarter this year exceeding any other period on record—and one could easily conclude that this is an important driver of inflation.

Had profit margins not increased, then a naive estimate suggests overall prices in Canada would be 1.2 percent lower.The math doesn’t really matter, but if you’re curious I estimate this using changes in price-cost markups. Specifically, I estimate the markup as 1/(1 – profit margin). That is, if profits are ten percent of sales then the markup is 1/0.9, which implies prices are 11.1 percent above costs. I then hold markups fixed at Q2 2021 levels and estimate prices in Q2 2022. Instead of inflation in the second quarter exceeding 7.5 percent, it would have been 6.2 percent. This implies roughly one-quarter of Canada’s unusually high inflation can be accounted for by rising profit margins.

It would be a mistake to end the analysis here, however.

A detailed look at individual sectors reveals a simple story behind these changes and also reveals why rising profit margins are not a driver of inflation. The same core driver of rising inflation, it turns out, is also causing higher average profit margins.

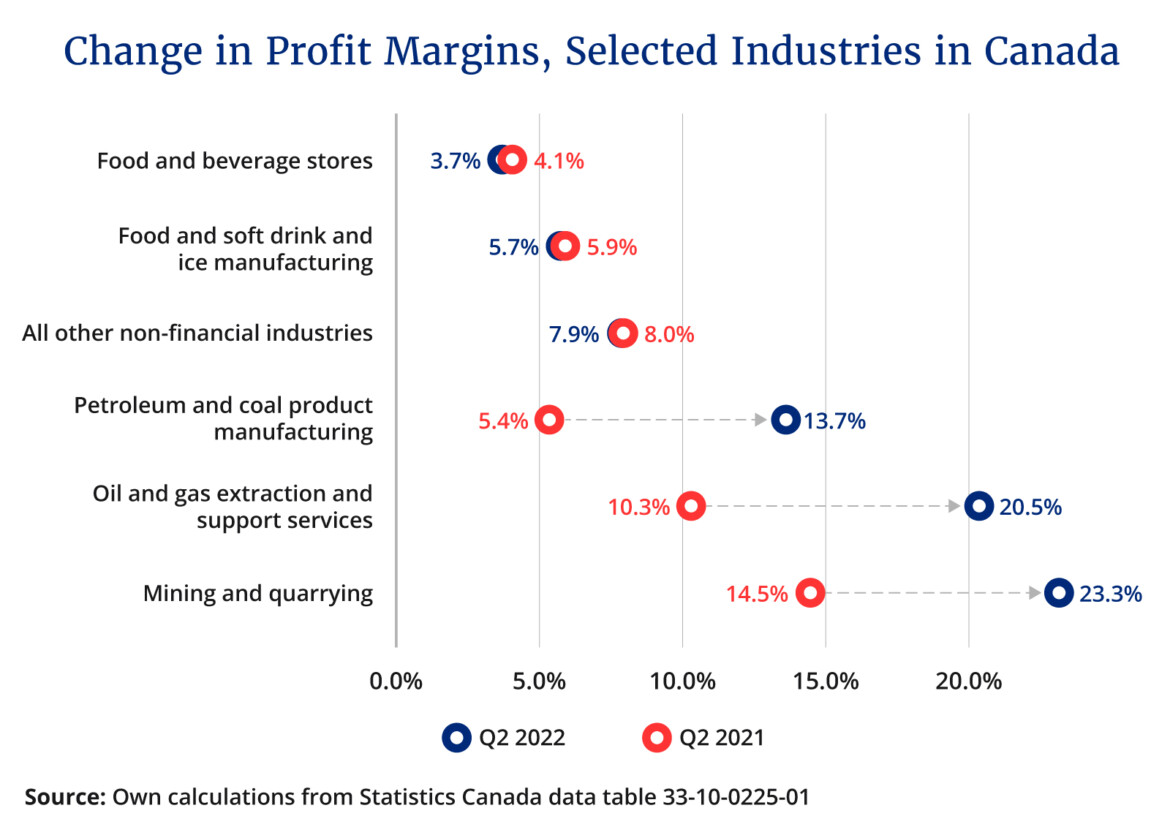

To see this, consider the mining, oil, and gas activities (including refining and petroleum product manufacturing) sectors. Together, they account for over 70 percent of the increased profit levels in corporate Canada—nearly $18 billion of the total $25 billion increase between Q2 2021 and Q2 2022.

But this is not due to rising market power. The prices of commodities they sell are set on global markets. Producers in Canada are largely price takers and while they benefit from high prices they are not the cause of them.

Outside of these areas, rising profits are entirely due to higher sales volumes rather than rising market power. Profit margins have been fairly steady at around 8 percent. I display these margins below, red for the second quarter of last year and blue for the same period this year.

Rising grocery prices—the focus of Mr. Singh’s attention—also does not reflect rising profit margins. In fact, food stores and food manufacturing both have lower profit margins this year than last.

One can even see this in the financial statements of large food retailers. Loblaws, for example, reported a net profit margin of 3.04 percent in the second quarter of this year and 3.03 percent in the second quarter of last year. Their rising profits are due entirely to rising sales, not increasingly uncompetitive behaviour as some suggest.

The entire increase in average markups in Canada are therefore related to rising global energy and commodity prices.

To be clear, this does not mean governments should not be concerned about profit margins in corporate Canada. Some sectors have significant domestic market power and likely charge higher prices than if more competition prevailed. Certain agricultural products (such as dairy), air transportation, telecommunications, and several other sectors, all benefit from high barriers to entry that governments deliberately enact. Liberalizing these sectors may, in the long run, be a source of lower prices. But while prices are higher than they otherwise would be, the change since last year—which is relevant for inflation rates—is immaterial.

One can also look at these developments and conclude that energy price regulations or windfall profit taxes are an appropriate response. We have seen that historically in Canada—most notably through the National Energy Program. This would indeed lower energy prices domestically, and therefore also lower measured inflation rates, but there are a whole host of other problems such intervention would create. The costs would almost surely exceed the benefits for Canada’s economy as a whole. But whatever one thinks of the merits of such policies, it is an entirely separate issue from understanding why inflation rates are rising.

There are of course important issues to explore and debate when it comes to the level of competition in certain areas of corporate Canada, and there are also many overlapping causes of rising consumer prices. But when it comes to claims that “greedflation” is a key driver of recently rising inflation rates, the data is very clear: it’s not.

Recommended for You

‘Mexico is better placed than we are’: What happens if Trump cuts Canada out of CUSMA?

‘Oddly, it might benefit Poilievre’: Hub Politics break down Carney’s latest floor-crossing coup

Why neither Carney nor Poilievre is rushing towards a snap election

How the risk of separation could cost Alberta thousands of jobs