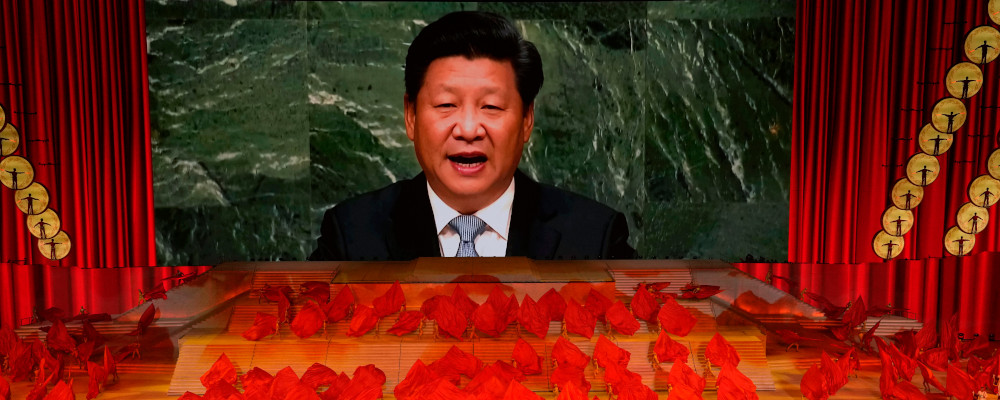

Over the years, Zhang Weiwei has emerged, both domestically and internationally, as one of the most vocal and faithful advocates of the “China Model”. Notorious for his debate with Francis Fukuyama back in 2011, Zhang has written numerous books and hosts his own political talk show produced by Chinese state media. He was even invited to address top leaders in the Politburo earlier this year on how to “improve the Chinese narrative”, a euphemism for its ideological propaganda. The party’s approval meant that his views are unchallengeable in China (in academia or beyond), and Western media often falsely equate the monopolized party perspective Zhang presents as truly representative, despite the diversity of Chinese perspectives that actually exist.

While his political agenda is clear, Zhang’s polemical arguments and tactics do warrant a closer examination. In a recent interview, Zhang grounded the superiority of the Chinese system of governance in three key areas: 1) China as a unique “civilizational state” with historical and cultural traditions which are incompatible with Western political and economic models; 2) the Chinese political system as a meritocracy in its leadership selection that is also a distinct form of democracy more advanced than that of the West; and 3) China’s unprecedented economic growth as a peaceful nation tolerant of religious and cultural differences. Rebuttals to each of these assertions are easily made.

Describing China as a civilizational state is common among defenders of the China Model. In his book “The China Wave: Rise of a Civilizational State”, Zhang justifies the Chinese Communist Party’s autocratic rule as a continuation of China’s historical tradition of a unified ruling entity. He asserts that China is the only state in the world with a continuous civilization, and by virtue of its long history and unique culture the country will follow its own historical logic and develop its unique path to modernity—one that is distinctively different from the Western model.

However, civilizational exceptionalism is often an artificial construct that flattens the complexities of history to a singular narrative. It was used extensively by conservative literati in China and Japan in the late 19th century to resist political reform. The use of civilizational rhetoric is not limited to non-Western countries either. Some proponents of American exceptionalism like to invoke what they refer to as the country’s distinctive cultural traits to justify claims of superiority. In that sense, Zhang’s insistence on calling China a civilizational state is best understood as a veiled attempt to boost Chinese nationalism. Despite a nominal rejection of the nation-state, his definition of a civilizational state, including “unique language, politics, society and economy” is taken straight out of a nationalist’s toolbox.

Even if we take the concept at face value, we will soon encounter difficulties. Invoking China as a civilizational state has been used repeatedly to reject universal human rights and democratic values, but Taiwan, which shares similar civilizational traditions with China, has successfully transitioned to a thriving democracy.

Zhang himself likens Rome to a civilizational state, but the Roman Republic degenerated into an empire and eventually fell apart. ISIS can be regarded as a contemporary attempt to revive the Caliphate, the Islamic civilizational state, but it has proven to be a disaster for humanity. At the end of the day, apart from stating the obvious fact that every country is different, the civilizational state excuse cannot explain how and why a country chooses a particular path, nor can it offer the basis for justifying a country’s political system. In fact, it cannot really explain anything.

Nevertheless, Zhang extends from this argument of cultural distinctiveness and makes a second set of bold assertions labeling the Chinese model as better governed, more meritocratic, and more advanced than what he calls the “U.S. model of democracy from the pre-industrial era”. Not only did Zhang reject the term “authoritarianism” used by political scientists, but he goes further in claiming that it is a high-functioning form of democracy called “democratic centralism”. While it sounds ludicrous to most Westerners, it is in fact echoed by the CCP as the official position in its latest white paper entitled “China: Democracy That Works”.

There are three common tactics used by CCP apologists to defend the impossible, and Zhang has used combinations of all three. Firstly, they can define democracy narrowly as “one person one vote”, rather than the whole package of civil liberties and constitutional institutions such as the separation of powers and the rule of law. This line of reasoning is also used by others like Eric Li, making it easy to discredit electoral democracy as outdated and ineffective. Alternatively, they can also use Orwellian doublespeak to obscure and subvert the meaning of democracy by performing various definitional sleight of hands and providing alternative definitions. Lastly, if all fails, they can always reject the term altogether, in favor of other standards such as popular support, economic achievements, or political meritocracy.

Even by these alternative standards, the Chinese model’s superiority over liberal democracies remains highly contested. Popular support in China is largely a product of “manufactured consent” through decades of propaganda and censorship. Imagine if every single person in America grew up with only Fox News and pro-Trump messages permeated throughout society with no alternative voices allowed to exist. It wouldn’t come as a surprise that the vast majority of Americans would be supportive of Trump, regardless of his actual performance.

Likewise, the economic progress China has made in the past 40 years since Deng’s market reform was undoubtedly remarkable, but it is not as “miraculous” as Zhang would like us to believe. China’s GDP per capita remains only one-sixth that of the U.S., and, far from poverty elimination, more than 40 percent of Chinese people (roughly 600 million people) still live on a monthly income of merely 1,000 yuan ($140 USD). Other countries, such as South Korea, have achieved similar feats within a generation while also transitioning to a democratic system.

Attributing all economic gains to China’s political arrangement is a gross over-simplification. For every “miracle” that Zhang claims, we can find an equally disastrous episode in modern Chinese history: is the Great Famine or the decade-long chaos of the Cultural Revolution also part of the great success story of China’s authoritarian system?

The conflation of the Chinese political system with meritocracy is not new either. Other proponents of the China Model like Daniel Bell and Kishore Mahbubani also claim that China enjoys meritocratic leadership. But this is a false dichotomy. Western democracies also have strong elements of meritocracy, as most politicians need proven track records to be electorally successful. The fact that Chinese national leaders must first serve as county and provincial chiefs is no proof of meritocracy either. It is merely a prerequisite to the top position and barely reflects competence. Most China specialists would agree that a variety of factors such as patronage, factional in-fighting, corruption, and ideological alliance play critical roles in leadership selection, and the domination of the so-called “princelings” in Chinese politics is well-documented.

Finally, Zhang assures us that China intends a peaceful rise focused on economic development. Did he forget to update his talking points from 10 years ago? China has pushed for an aggressive foreign policy under Xi’s leadership since 2013, abandoning Deng’s guiding philosophy of “hide your strength, bide your time”. Having engaged in over a dozen border disputes on land and sea, its neighbours certainly don’t view China’s rise as very peaceful. Furthermore, China has repeatedly used its political and economic power to bully other nations and international companies to fall in line with its political directives, Canada itself being a victim of CCP’s hostage diplomacy with the arrest of the two Michaels.

Confronted with questions on China’s domestic human rights or issues relating to Hong Kong, Xinjiang, or Tibet, the classic rhetoric is to deny or to deflect by engaging in whataboutism (U.S. bashing being Zhang’s favourite hobby). While some of his criticisms of the U.S. are apt, his blatant double standard is telling.

Zhang can shamelessly tell these half-truths and lies with a calm smile because he knows the real audience for his message is not Western viewers, but the nationalistic crowds at home and his top priority is to win brownie points with the CCP. If he fails to convince the foreign audience, he can always blame it on anti-China bias and Western arrogance.

Recommended for You

‘Our role is to ask uncomfortable questions’: The Full Press on why transgender issues are the third rail of Canadian journalism

Need to Know: Mark Carney’s digital services tax disaster

Theo Argitis: Carney is dismantling Trudeau’s tax legacy. How will he pay for his plan?

Kirk LaPointe: B.C.’s ferry fiasco is a perfectly Canadian controversy