Across the Western world, conservatism is undergoing an identity crisis. The rise of right populism and a perceived failure to effectively react to the COVID-19 pandemic have caused significant rifts in the conservative coalition. The challenge to a conservative leader, therefore, is to cobble together a stable coalition based on a political philosophy capable of corralling the disparate factions while at the same time maintaining the necessary appeal to win over the general population.

From the standpoint of practical politics, internal factionalism and fractiousness are a recipe for electoral disaster—Canadian conservatives need not be reminded of the experience of the 1990s. Some myopic commentators have suggested that conservatives abandon their longstanding stance on electoral reform in response to this political environment. These commentators argue that those with centre-right political perspectives do not have enough in common with each other to remain in one party. Instead, they say that the movement would be more successful if it were divided between different parties in a different electoral system. While there is scant evidence that such a move would result in substantial policy differences from our current track over the medium to long term, it is nevertheless a defeatist mentality.

Successful political parties optimize themselves to take advantage of the system’s incentives. Just because a party consistently loses does not indicate a fault in the electoral system, but rather the party’s responsibility to successfully organize to take advantage of the incentives on offer. The federal Liberals are an illustrative example—after their near annihilation following the 2011 election, they optimized their platform and party machinery to appeal to a cross-section of the electorate that would deliver them the most seats.

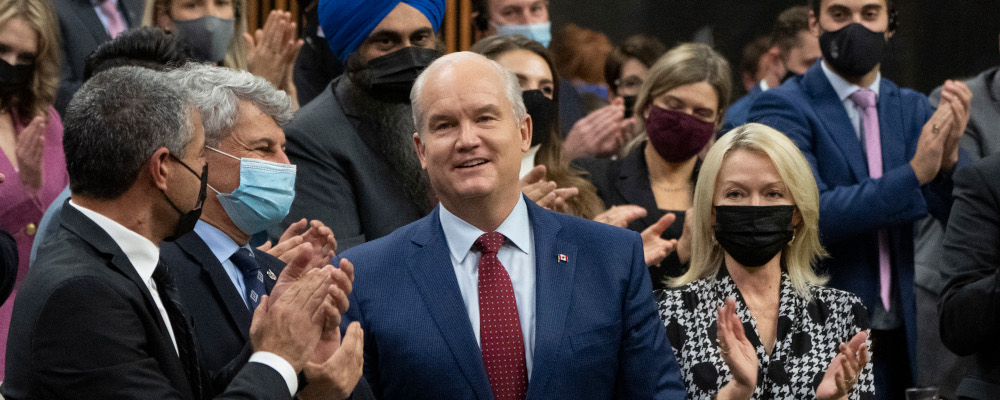

Arguably, Erin O’Toole tried this and failed. The commentariat widely lauded the Conservative Party platform as a centrist document that appealed to a wide swath of working-class and suburban voters. Yet despite best efforts, the party is no better off today than it was following Andrew Scheer’s defeat in 2019. Since the election, O’Toole’s approval rating has plummeted, and the coalition appears as fractious as ever. This suggests that the problem is more profound than electioneering and policy. Conservatives have a serious branding problem, the root of which goes to the movement’s core philosophy. An examination and recasting of this philosophy is required, and conservatives themselves should understand and evaluate what they stand for.

The conservative coalition is broadly divided into Right Populists, Burkeans, and Conservatarians. These factions and their names are a sketch—the members of these groups do not necessarily self-identify as such, and most individual self-described conservatives have certain tendencies that borrow from each category.

First, the Right Populists. Like much in Canadian politics, the Right Populist is typically marked by a strong attachment to a particular geography. While central and Atlantic Canada was the traditional battleground between (Progressive) Conservative and Liberal parties, endogenous populist movements have periodically arisen from Western Canada and Quebec and occasionally enjoy modest electoral success. These movements emerge from a perception that the country’s population centre (the Windsor-Quebec City corridor, i.e., the Laurentian elites) ignores their concerns. While this brand of populism has arisen out of local grassroots movements and real and perceived federal overreaches, the anti-establishment nature of the movement as it exists today draws inspiration from global populist movements.

At the risk of oversimplification, we can include MAGA, Brexit, and the other global reactionary political movements as the main ideological inspirations for this cohort. It is a conservatism of rhetoric, primarily concerned with real and perceived grievances with the liberal elites. It believes that life will be better if Canada (or parts of Canada) are freed from the yoke of the Laurentian elite. These elites oppress the French language, prevent the oil from flowing, force vaccine mandates, and peddle in oppressive “wokeism.” It is true that populism emerges from grievances perceived or actual.

Still, the populist fails to produce cures that are better than the disease. Their solutions (balkanizing the country is a popular one) are motivated primarily by emotionally charged grievances rather than finding workable solutions within the existing political order. For a conservative leader interested in preserving (or conserving) a recognizable conception of Canada, the use of the Right Populists begins and ends with the Right Populists’ ability to identify fractures in Canadian society.

This brings us to the second type of conservative, the Burkeans. Suppose the Right Populists are concerned with a vision of the country that firmly rejects the overly centralized notion of Laurentian liberalism. In that case, the Burkeans are concerned with preserving the status quo and only making tweaks and changes to that status quo if, and only if, the status quo is producing discord or emergencies.

The basis of the Burkean thought suggests that the present is good and that the present is good because it is ours. In effect, the lesson from this strand of thought is that we are good, and things around us are good, and while there are trivial things that could improve and progress, we are successful because of the collective elements around us. This is the politics of comfort: uncertainty is bad, and when we change things, we may not always predict the consequences. Unlike right populism, Burkean thought has value to run a government, as it provides a systematic way to approach and solve problems. However, in the 200+ years since the French Revolution, for those who wish to find a philosophical grounding as distinct from liberalism, Burke offers us little guidance. Burke himself explicitly rejected philosophy and instead focused on the immediate problems of the now. Accordingly, Burkeans today would not question the liberal underpinnings of our society and law itself, only the effectiveness of particular political choices. This is fine for governing but hardly makes for an inspiring basis for a political campaign which typically requires a vision coupled with a narrative.

The third type of conservative is the conservative-libertarian (i.e., the “Conservatarian”) or the “Classical Liberal.” The Conservatarian is motivated by the ancestor of old liberal ideology, which fell out of favour with modern liberals following the Oxford Manifesto of 1947. It is inspired by figures like Locke, the Founding Fathers of the United States, and contemporaries like Hayek, Rand, and Friedman. Conservatarians are wedded to an ideological commitment to what they believe society should be and draw their morality from this ideology. Since right-wing economics implicitly supports the existing class structure, they find themselves in the conservative family, but not because of inherent conservatism. Their adherence to a specific ideology makes them opposed to modern liberals, progressives, and socialists. Their alliance to the conservative movement is a marriage of convenience: they are nevertheless committed to liberalism. The only difference is that they think modern liberals are doing liberalism wrong.

The core of liberal belief and the conservative coalition that has sprung from criticism of the liberal movement is this idea that humans are best understood as individuals and that individual rights and freedoms must protect individual differences. It is worth noting that this idea of human nature is emergent from Enlightenment philosophies. These three forms of conservativism have aligned and are considered conservative only because our political system encourages this alliance as their interests are opposed to modern liberal, progressive, and socialist causes. Notably, each is defined by its relationship to liberalism. The definitions of these groups entirely break down without a conception of liberalism as it exists in the modern world. As a result, the Canadian understanding of conservatism as a concept only exists in the framework presupposed by liberalism.

If your goal is to create an ideologically independent conservatism, this framework is untenable. Liberal thought suggests that the core of society is the individual and that individuals operating freely, so long as they respect certain rules and other individuals, is the best way to organize society.

The basis of the liberal conception of morality does not give us a cohesive answer as to whether something is good. It tries to align itself with a pluralistic and individualized account of “goodness.” Whether something, someone or even the nation is good is a question personal to individualism. The modern liberal state does not concern itself with this. However, borrowing from the Burkean tradition, we start from the position that our society, nation, and institutions are fundamentally good. Conservatives, therefore, should start from the position that Canada is good and the government should promote the public good, as opposed to the liberal ambivalence to public goods.

Conservatives should start from the position that Canada is good.

We must consider political philosophies that developed pre-enlightenment as an alternative conception of human nature, distinct from liberalism. Aristotle, for example, suggested that humans at their base are only fully human when they can properly exist in a society—not when given total freedom. Therefore, society and our institutions should be correctly understood as places to imbue virtues into children and adults. Morality does not come from the first principles of a particular ideology but is drawn from experience living harmoniously with others.

From personal experience, most of us would note that conflict is unavoidable if people have different interests, backgrounds, and points of view. Accordingly, we should encourage social institutions to enforce and promote good, pro-social behaviour. Otherwise, conflicts between individuals with different values are inevitable. The proper role of the state then is to impose guardrails to prevent harm to others but that allow and support social institutions in shaping individuals into moral and productive members of society.

Conservatives today, broadly, suggest that government is “too big,” and its overreach and size stifles goods (both public and private goods) from emerging. The common refrain is that “if the government gets out of the way, the goods produced by private individuals, organizations, and institutions will be able to flourish.” This perspective frames Conservatives as “takers” or “destroyers,” which has now in practical politics evolved into a pervasive branding problem: the only solutions that Conservatives are offering is to cut things.

In a public health and economic crisis, it is hard to argue to the median voter that the government should be doing less when people are still suffering. Instead, conservatives should consider starting from a different perspective. Instead of asking “is government too big?”, which presents itself as monodirectional, conservatives should begin by asking the question “is the government performing or promoting the public good?” This should then be followed by “what is the best way for the government to promote the public good?”

Sometimes this may mean the government should pull back; other times, it may expand; or other times still, it would create a fertile ground for private goods to take root. Being able to propose and frame a conservative vision in this manner would serve to ground a more positive Canadian conservatism as distinct from Canadian liberalism.

Recommended for You

‘Another round of trying to pull capital from Canada’: The Roundtable on Trump’s latest tariff salvo

‘We knew something was coming’: Joseph Steinberg on how Trump is ramping up his latest tariff threats against Canada

Rudyard Griffiths and Sean Speer: Canada’s high-stakes standoff with Trump

Carney’s next budget will be built on a shaky fiscal foundation