Ontario and Canada in the aftermath of the strains of the COVID-19 pandemic are in a protracted health system crisis marked by waiting lists, ER shutdowns and shortages of critical health professionals including doctors and nurses.

Ontario’s Health Minister Sylvia Jones has argued that the closures of ERs in Ontario is not unprecedented and in this regard she is indeed correct. In the past, there have been issues with ER staffing crunches particularly in December as the holiday vacation season and flu season came together to create similar disruption. However, at the same time this is not best retort for the minister because it essentially means that this is a long-standing problem that has not been addressed and has now been aggravated by the pandemic.

Notwithstanding the fact that about one third of Canadian health care is privately financed and physicians are largely independent contractors, solving the problems of the health system has again electrified the third rail of Canadian politics — whether or not there should be more privatization in health care.

Naturally, the perennial debate over privatization has been accompanied by the other usual approaches to improving the system including more resources as well as reorganizing delivery to make the system more efficient. One might argue that this time is different given the staff shortages have worsened working conditions for doctors and nurses and longer shifts are burning out staff.

At the same time the call for more resources should be weighed against the experience of the aftermath of the Romanow Report nearly two decades ago which led to the six percent Canada Health Transfer Escalator that was supposed to buy transformative change in the health-care system. Yet, two decades later here we are facing a lot of similar issues — overcrowded ERs, lack of after-hours access to family physicians, waiting lists.

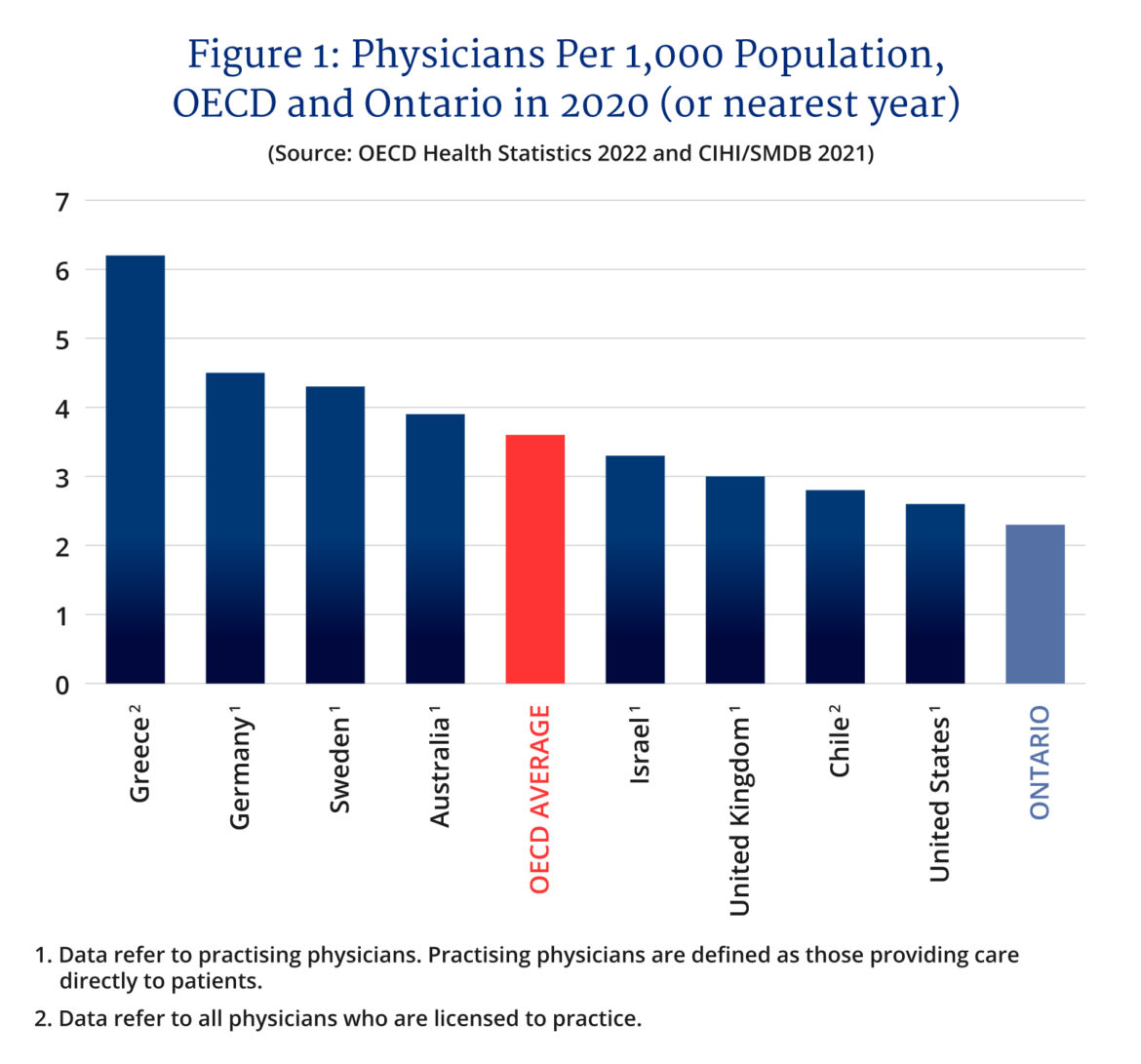

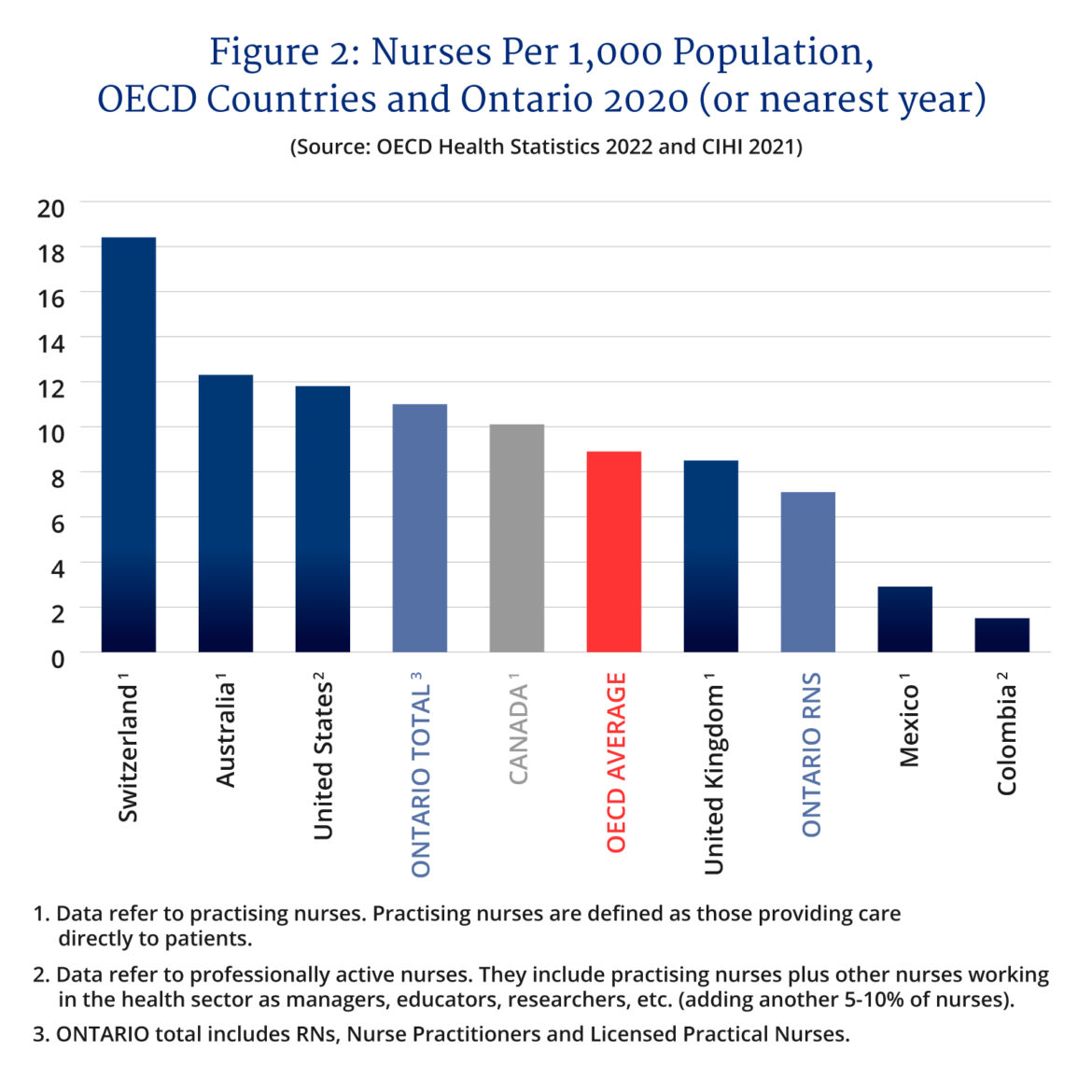

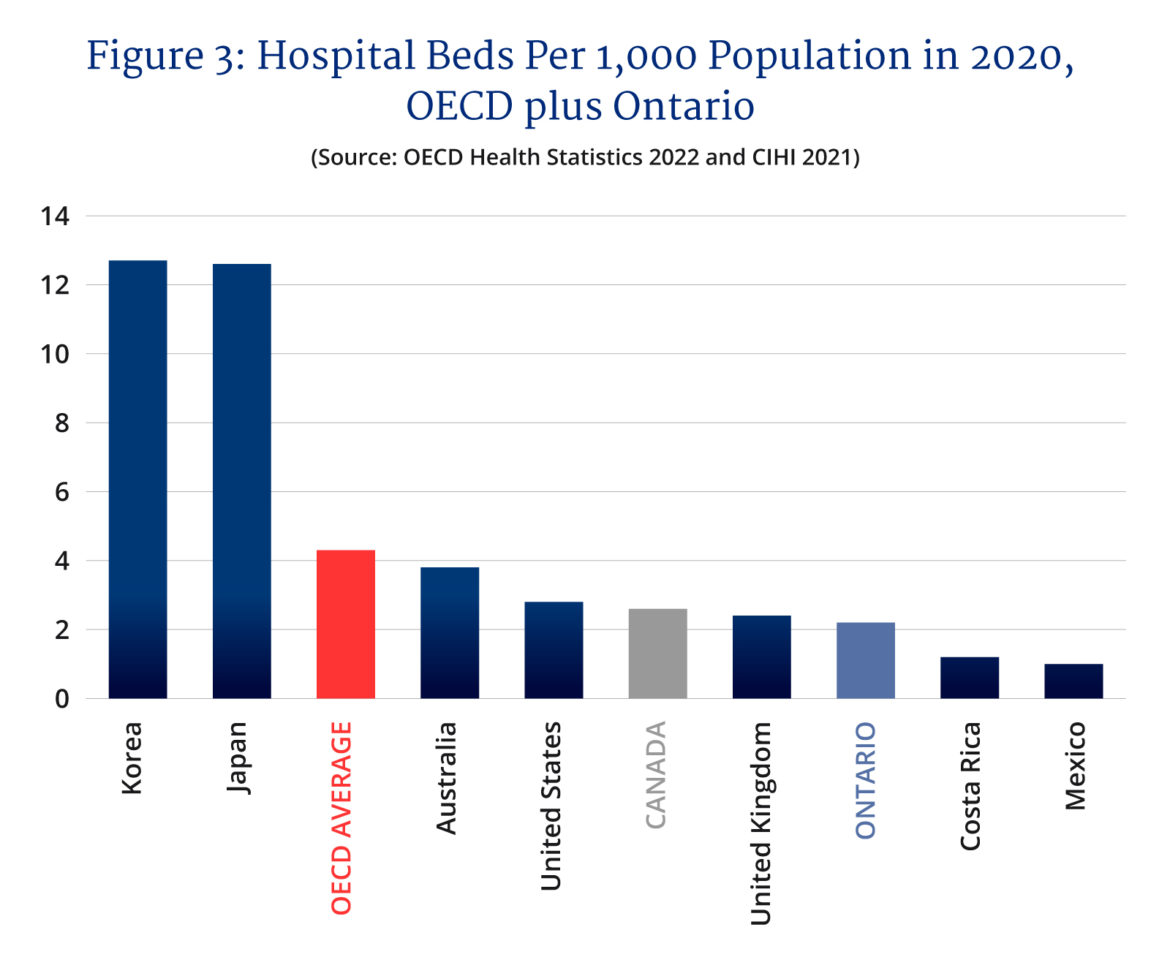

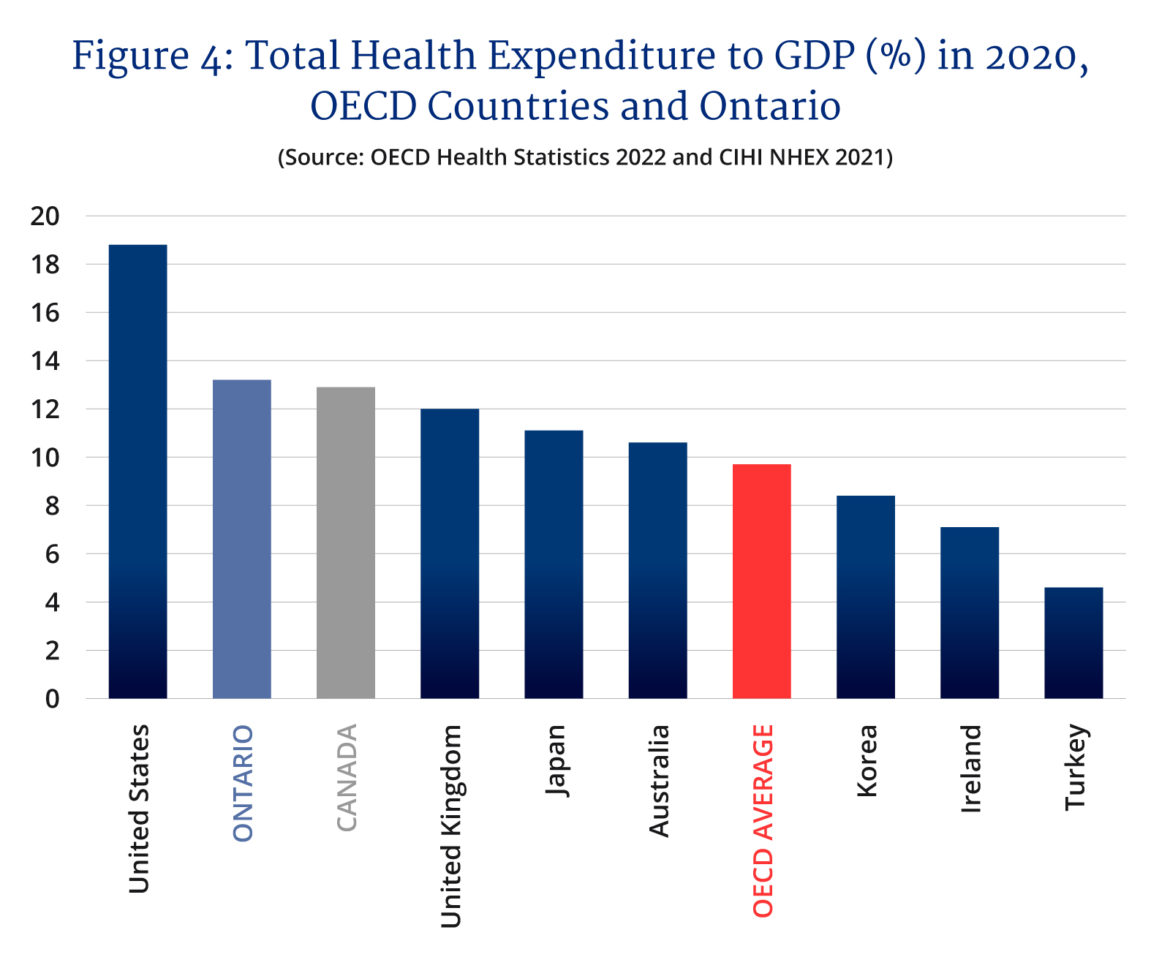

Using Ontario as a proxy for the Canadian health-care system it is useful to examine the claim that the system is under-resourced. A comparison of health resource indicators for Ontario and Canada with the other major countries of the developed world — the OECD countries — provides an important set of benchmarks and to that purpose, the following four charts are offered.The data sources for these charts include the 2022 edition of the OECD Health Statistics, the Canadian Institute for Health Information National Health Expenditures Database (CIHI NHEX 2021), and assorted reports from the CIHI databases on hospital beds, physician and nursing supply. International comparisons are useful, but it needs to be kept in mind that despite the best efforts at standardization there are cross-country differences in reporting health indicators making comparisons a challenge. Yet, a story does emerge.

Figure 1 presents ranked physicians per 1,000 population for 38 OECD countries along with an OECD average and Ontario. The number ranges from a high of 6.2 for Greece to a low of 2.1 for Turkey with the OECD average at 3.6. If Ontario were a country in this ranking, it would have the second lowest number of physicians per 1,000 at 2.3 — just ahead of Turkey and behind Columbia. Put another way, Ontario’s per capita physician numbers are 36 percent below the OECD average. Note also, that Ontario also is about 15 percent below the Canadian physician figure despite nearly a decade of expanding medical school physician supply.

Figure 2 repeats the ranking for nurses and here there seems to be considerably more variation in the definition of nurses so two figures are presented for Ontario — total nurses per 1,000 which includes nurse practitioners, RNs, and licensed practical nurses and just RNs alone — the backbone of hospitals.

The ranking here ranges from a high of 18.4 nurses per 1,000 population for Switzerland to a low of 1.5 for Colombia. Here, in incomparable political fashion one can satisfy politicians, lobbyists, and health advocates of all stripes with Ontario either above or below the OECD average depending on which nursing indicator you wish to use. Ontario either has 11 nurses per 1,000 population putting it in the top third of the OECD or 7.1 placing it more within the bottom third.

Figure 3 presents a ranking of hospital beds per 1,000 population and here the top performer is South Korea with 12.7 beds per 1,000 followed closely behind by Japan at 12.6. At the bottom are Costa Rica and Mexico at 1.2 and 1.0 beds respectively. Ontario and Canada are close to the bottom of this ranking with Canada at 2.6 and Ontario at 2.2 — both below the OECD average of 4.3. If it is any consolation, our two Atlantic Anglosphere compatriots with whom we share many cultural similarities — the United Kingdom and the United States — are also near the bottom with the United States at 2.8 and the United Kingdom at 2.4. Canada also often considers itself a Nordic country and it should be noted that when it comes to hospital beds, Denmark and Sweden are also close by.

Given health resource indicators that are often at the bottom of rankings and at best mid-ranked, one would think that the obvious solution to Canada’s health system woes is simply more money. Yet, if one examines Figure 4, some might be surprised to see that when it comes to an aggregate measure of total resources devoted to health such as the total health expenditure to GDP ratio, Ontario and Canada perform very well. In 2020, the health expenditure to GDP ratio in the OECD countries ranged from a high of 18.8 percent for the United States to a low of 4.6 percent for Turkey with the OECD average at 9.7 percent. If Ontario were a country, it would move second place Canada to third place with a ratio of 13.2 percent to Canada’s 12.9 percent. Ontario’s health expenditure to GDP ratio is 36 percent above that of the OECD average and yet when it comes to physicians per 1,000 it is 36 percent below, hospital beds 49 percent below and nurses — if you use RNs — 20 percent below.

Now of course, one might quibble that 2020 is a bad year to use for a health expenditure to GDP ratio given it was the pandemic year, but all these countries were hit by the pandemic, and all took a hit to GDP while seeing their health spending increase. Still, it is a point well taken. If you were to do this ranking using 2019, one would find the average across the OECD at 8.8 percent with the top rank going to the United States at 16.7 percent and the bottom place to Turkey at 4.4 percent. Ontario comes in at 11.2 percent behind second place Germany at 11.7 percent and third place Switzerland at 11.3 percent. Then come France, Japan and Canada who range from 11.1 to 11 percent. Needless to stay, Ontario is still at the top of these rankings.

Some countries devote a lot of their GDP to health and rank high in health system resources, some spend little and rank low in health system resources while some spend a lot and rank low in the quantity of resources. We seem to be in the third category. It does not mean you have a bad health care system, but it does represent a choice of how we have chosen to structure and run our health systems. Ontario and Canada in general pour a lot of money into health care but have fewer health resource input units, so to speak, meaning it pays them a lot but also runs them very intensively. Our system is efficient in the sense we are getting relatively good overall outcomes with fewer doctors, nurses, and hospital beds.

We generally also pay our health system workers and professionals more than in many other countries and part of the trade-off is that they are run off their feet in return for the compensation they get. The problem now is that after two years of pandemic burnout and a backlog of surgeries combined with COVID-19 resurgences, it is not possible to wring blood from a stone. At the same time, many health sector workers are seeking better work-life balances though not necessarily reduced compensation. Case in point, new physicians today are not the draft horses of yesteryear and generally it takes two to three of them to take on the caseload of a retiring physician — something that is going to happen more given the age profile of the medical profession. It does not help that over the years administrative processes focused on accountability take up more physician time than it used to, thereby also reducing time with patients.

So, Canada and Ontario have the health-care systems they designed.

Since the 1990s, it has evolved into a just-in-time delivery model that seeks to move patients through the system quickly with reduced but historically well compensated technical inputs. It is technically quite efficient. Most of the time, the system works well, and nobody bats an eye. Even the glacier of an aging population and its increased medical needs — until the pandemic — was being accommodated if with the occasional hiccup.

Unfortunately, it was never designed for an extended pandemic that coincides with staff burnout, a surgical backlog, and a wave of retirements on top of everything else. Given what we already spend on the system, one wonders whether more resources poured into it via increased federal transfers or more private sector involvement is something anyone is willing to pay for? Can we obtain more resources while spending the same amount or less?

A politician that can fix this system will truly be a paragon of patience, wisdom, and virtue.

Recommended for You

Need to Know: Mark Carney’s digital services tax disaster

Sean Speer: Investing in critical minerals isn’t just good business, it’s a national security imperative

Theo Argitis: Carney is dismantling Trudeau’s tax legacy. How will he pay for his plan?

The state of Canada’s economy halfway through 2025