This essay was originally published on Kenneth’s Substack SHuSH, which can be found here.

We need to talk about Indigo. As you know, it’s Canada’s biggest bookstore chain, with 88 superstores and 85 small-format stores. It sells well over half the books that are bought in stores in Canada, with Walmart, Costco, and independent bookstores accounting for most of the rest.

One problem with Indigo is that it’s failing. The other problem is that it’s abandoning bookselling. Yes, that sounds like a Woody Allen joke, but it’s not funny from a publishing perspective. We depend on Indigo.

The company’s finances have been ugly for some time. It lost $37 million in 2019, $185 million in 2020, and $57 million in 2021. Things looked somewhat better in 2022 with a $3 million profit, but the first two quarters of 2023 are now in the books (it has a March 28 year end) and Indigo has already dropped $41.3 million.

That the company lost money in its first two quarters isn’t the end of the world. Indigo is a third-quarter business. All the magic happens over the holidays. The trouble is that the $41.3-million loss is about $10 million more than the 2022 loss over the same period. That’s the wrong direction; things were supposed to improve with COVID’s foot lifted from the neck of the retail sector. The company’s share price, which seemed ready to recover in June, has since dropped 30 percent, down to $2 (from a high of about $20). Without an absolute blockbuster of a holiday season, Indigo is likely to be back in the red on the year.

While all this is going on, Indigo has been backing out of the book business. If you follow the firm’s marketing, it’s all about “intentional” and “purposeful” living (its press releases sound like Gwyneth Paltrow circa 2008). Indigo is intentionally and purposefully attempting to re-establish itself as a general merchandise supplier to youngish women.

This is not news. As far back as its 2013 annual report, Indigo said it was in “the early stages of a journey that is taking us from our position as Canada’s leading bookseller to our vision of becoming the world’s first cultural department store.” It saw toys, paper, home decor, fashion accessories, and gift sales as the future of the business.

As far as I can tell, 2014 was the first year Indigo reported its book and general merchandise sales separately. Books, once practically the whole of its business, were by then down to 67.4 percent of total sales, with general merchandise accounting for 28 percent. By last June, books were down to 53.6 percent and general merchandise was 41.5 percent.

Indigo has made roughly half of its retail space devoted to books go poof and the transformation is far from finished. At its showcase New Jersey location, the mix is 40 percent books and 60 percent general merchandise, and it’s specializing in a particular kind of book. “We found a niche,” said an Indigo executive. “We became the preferred destination for New Yorkers for coffee table books. In fact, every decorator in New York comes to that store to buy these big format coffee table books for their clients’ homes. So we go from books about décor to books as décor… That store has had an incredible year.”

In July, Indigo released this publicity photo for a new flagship store at Ottawa’s Rideau Centre. See any books there? All the company’s flagship stores are being refitted in this direction.

Existing stores, too, are seeing books squeezed out of the picture. I dropped by the Yorkdale location this week. It’s a large two-storey space in a mall, accessible only from the main floor, which means all the traffic is on the main floor.

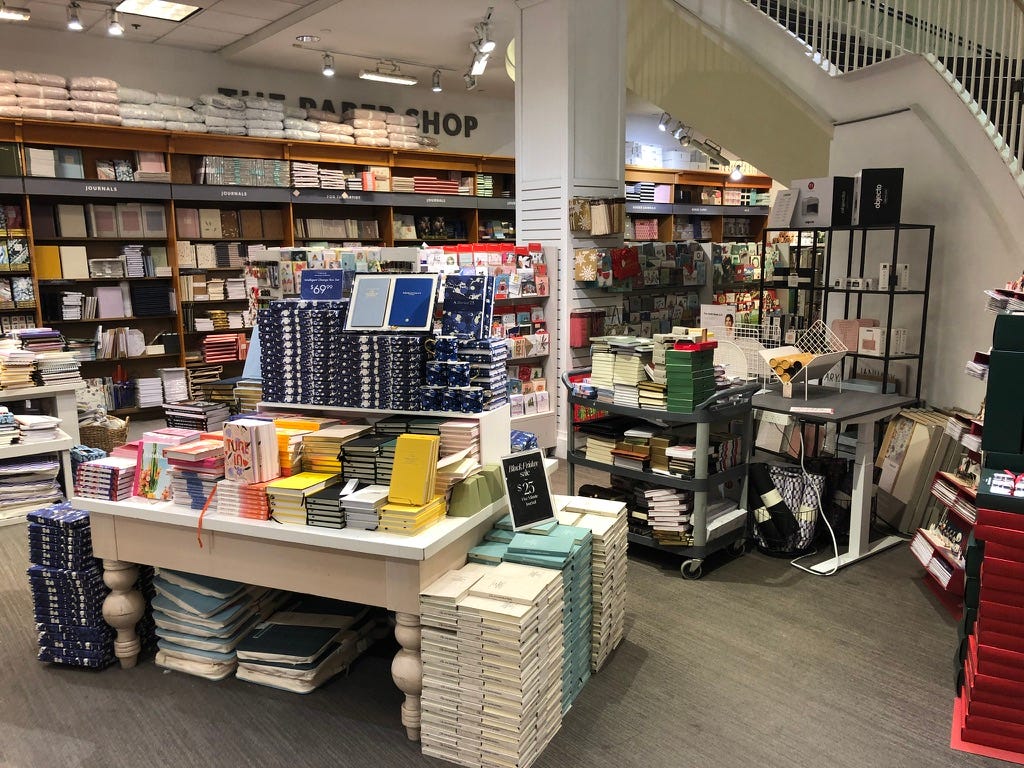

Here’s what you find on the main floor.

Merchandise for the bedroom:

Merchandise for the living room:

Merchandise for the kitchen:

Merchandise for your desk:

Merchandise for the holidays:

And, over here, a few books, bestsellers only.

That’s pretty much it for literature on the main floor and even in this corner, the book tables share space with general merchandise. I didn’t pull out my tape measure, but I’d guess well under 20 percent of high-traffic space is devoted to reading material.

If you want more books, you have to journey up to the dark and forbidding second floor. At least you avoid the crowds.

Two weeks ago, Indigo announced a deal with Adidas to bring sportswear into the stores.

Last year, it held a contest where kids-and-baby businesses competed for the right to open their own stores within Indigo stores.

The fastest-growing category of general merchandise at Indigo is its house brands, stuff it makes itself, cutting out the middlemen. Walk around an Indigo and you’ll see products labeled OUI, Nóta, The Littlest, Mini Maison, IndigoScents, Love, and Lore. All house brands; none have anything to do with books. This is a business that owner Heather Reisman learned in the last century, making private-label soft drinks for grocery chains. She’s returning to it now.

Indigo hasn’t come right out and said we’re through with books. It can’t, given that Heather has spent the last twenty-five years building herself up as the queen of reading in Canada. Also, the Indigo brand is still associated with books in most people’s minds and that won’t change overnight no matter how many cheeseboards it stocks. So Heather talks about a gradual, natural transition: “We built a wonderful connection with our customers in the book business. Then, organically, certain products became less relevant and others were opportunities.”

To be clear, books are irrelevant; general merchandise is the opportunity. Heather recently appointed as CEO a guy named Peter Ruis who has no experience in books. He comes from fashion retail, most recently the Anthropologie chain, which sells clothing, shoes, accessories, home furnishings, furniture, and beauty products. Anthropologie was hot in 2008, and it seems to be where Indigo wants to go today.

Fair enough. You own a company, you can take it in any direction you want, so long as your shareholders will follow. I don’t blame Heather for having second thoughts about the book business. (I have them every week. It’s a tough business.) But where does that leave readers, writers, agents, publishers, and everyone else who remains committed to books?

You’ll recall that Indigo and Chapters, between them, decimated the independent bookselling sector in Canada in the nineties. They are the principal reason Canada has so few independent bookstores today. You could probably fit the combined stock of all our independents into a handful of Heather’s stores.

The federal government let Heather’s Indigo buy Larry Stevenson’s Chapters in 2001, which gave her a ridiculously large share of the market. That shouldn’t have happened.

At the same time, with the help of some lobbying by Heather, the federal government made it clear that the U.S. chains, Borders and Barnes & Noble, weren’t welcome up here. The argument was that bookselling was a crucial part of our cultural sector and needed to be protected from foreign domination by the Canadian government.

In that spirit, Indigo also asked the federal government to prevent Amazon from opening warehouses in Canada. That request was denied in 2010, which is about when Indigo began its transition out of books.

One can see how Heather might feel betrayed by the federal government. Instead of protecting bookselling, it swung the door wide open for Amazon. You said I wouldn’t have to compete!

All the same, one can also see how Canadian readers and the Canadian literary sector might feel betrayed by Heather and Indigo. They bought control of the Canadian bookselling market; now they’re washing their hands of it.

I put more onus on the feds—you intervene in a market, you own it—but assigning blame is a useless exercise when none of the parties will accept it.

We’re left with a bookselling sector dominated in its bricks-and-mortar dimension by one firm spewing red ink and running for the exit, and in its online dimension by an international platform that could care less about anything Canadian and is also deprioritizing books.

Publisher’s Weekly reported last week that Amazon was eliminating roles in its books division, a decision that follows a summers-long effort by the company to reduce the number of books it was keeping in inventory and adds “more fuel to the feeling within publishing that Amazon is losing interest in its book business.”

Where this ends is anyone’s guess. It is interesting that Heather stepped down as CEO at Indigo a couple of months back (she remains executive chairman). This was followed by her husband and bankroll, Gerry Schwartz, retiring as head of Onex this month. Might be a lifestyle choice. Might be a sign that she’s about to unload Indigo.

My dream is that she sells, preferably to Elliott Advisors, the same private equity bunch that owns Waterstones in the U.K. and Barnes & Noble in the U.S. They seem to have figured out how to make a book chain work.

Meanwhile, as I said at the outset, the publishing sector needs Indigo. I wish the company a robust and highly profitable holiday season, and I hope books outperform for them.

Recommended for You

‘Disloyalty to a friend’: Sean Speer on the cultural tension captured by the recent clash between Don Cherry and Ron MacLean

Sean Speer: Maybe Ron MacLean is the one who needs to go

Evan Menzies: Calgary at 150: Why is it so hard to celebrate our history?

Howard Anglin: Canada is badly failing the ‘Tebbit Test’