Scaling up Canada: Professor Joseph Heath on immigration, injustice, and finding cooperative solutions to society’s problems

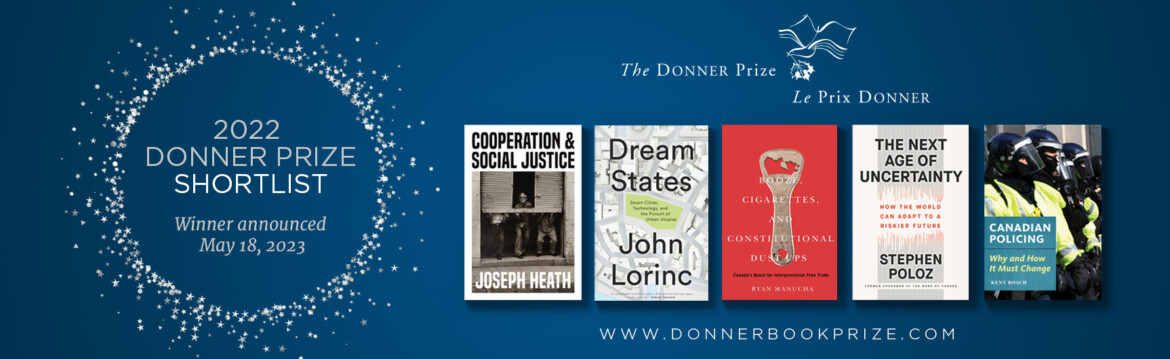

This episode of Hub Dialogues features Sean Speer in conversation with 2022 Donner Book Prize nominee and University of Toronto professor Joseph Heath about his nominated book, Cooperation & Social Justice.

They discuss the interplay between our institutional arrangements and the pursuit of social justice, scaling up our cooperative institutions, and how the Left and the Right differ in how they diagnose and tackle societal problems.

You can listen to this episode of Hub Dialogues on Acast, Amazon, Apple, Google, Spotify, or YouTube. The episodes are generously supported by The Ira Gluskin And Maxine Granovsky Gluskin Charitable Foundation and The Linda Frum & Howard Sokolowski Charitable Foundation.

SEAN SPEER: Welcome to Hub Dialogues. I’m your host, Sean Speer, editor-at-large at The Hub. I’m honoured to be joined today by Joseph Heath, a professor in the Department of Philosophy at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the University of Toronto. He’s the author of several books, including his most recent, Cooperation & Social Justice, which comprises six essays on the interrelationship between our conceptions of justice and the institutions that comprise modern society. Cooperation & Social Justice has been shortlisted for the prestigious Donner Prize for the best public policy book by a Canadian. The prize will be awarded on May 18th. Joseph, thanks for joining us at Hub Dialogues, and congratulations on the book and its success.

JOSEPH HEATH: Oh, thanks, Sean. Thanks for having me.

SEAN SPEER: Let’s start with the book’s key thesis. Listeners will be familiar with the idea that our institutions at some level reflect our societal values. You make the case that actually our institutions themselves come to influence the expression of those values in cooperative efforts, including public policy. What’s the interplay between our institutional arrangements and the pursuit of social justice? How does it manifest itself in some circumstances as a source of tension?

JOSEPH HEATH: Part of the idea is to think about justice in a somewhat less idealized way than we sometimes do. I’m in a department of philosophy, sometimes called the department of data-free speculation, where we just wax philosophically about what an ideal society would look like. That gets pretty boring after a while, in part because it’s not difficult to imagine an ideal society. It doesn’t really require a PhD to think about ways in which people could behave themselves better.

Where it gets hard, and where it gets interesting then, is when you realize that there are constraints that we’re subject to. Like in the case of social institutions, the simple fact is that people are self-interested. People are motivated by moral commitments, but they’re also motivated by their self-interest in a really complex way that’s actually really hard to understand and to model. It means that we can’t just prescribe moral solutions to social problems and expect everyone to fall in line.

We have to recognize that there’s going to be some sort of—we have to worry also about incentives, and the tendency of people to deviate from moral ideals and stuff like that. That’s where it gets really interesting is when you start thinking about ideals of justice but subject to the constraints that we’re subject to, the constraints of human motivation and of human knowledge, and stuff like that. Institutions, in a sense they realize ideals of justice, but they also represent the central constraints that we’re subject to, and we think about questions of justice because justice needs to be institutionalized.

SEAN SPEER: It’s common these days for social activists to talk about systemic barriers to equality or social justice, or whatever their goal. What’s the difference, if any, in your mind, between how they talk about systemic issues and your own thinking about these institutional arrangements?

JOSEPH HEATH: I think the biggest difference is that often—there isn’t necessarily a difference, but what I often see when people talk about systemic injustice or systemic racism, stuff like that, is they’re actually not thinking about it systemically. They’re treating the institutions as a bit of a black box. What people are often just doing is pointing to outcomes. This is something that’s happened in the U.S. discourse, in particular around race relations, where there’s been a shift away from thinking about process and a focus more on just brute outcomes.

There are various reasons why that’s happened, but it has one advantage, which is that if you want to diagnose structural injustice, it could be if you can point to disparities in the outcome of some institution or process then you can say, “Aha, there’s structural injustice.” It tends to be a very consequentialist way of thinking about justice. The problem with that is that there’s often, in some cases, just a lack of interest in actually popping the lid or opening the hood and trying to figure out how the institution is generating those kinds of injustices.

Often you get this shift where people say, “I’m not talking about individual discrimination, I’m just talking about structural discrimination.” You say, fine. There’s structural discrimination, but where does it come from? Often, the answer is just, “Oh, well, there must be some kind of individual discrimination going on there.” You get this bouncing back and forth between this individualistic way of thinking about it, and then this very broad outcome-based way of thinking about it. What’s missing there is actually the thing that I’m interested in.

Which is, what is it about the structures, the institutions, the systems that are systematically generating these disparities in outcomes? That’s an interesting conversation. Part of the reason why people don’t want to pop the lid or the hood, or whatever other metaphors, of the institutions, is that when you do start looking at what the mechanisms are that generate the certain kinds of disparities, often, you have to be morally flexible or open-minded in the sense that what looks like an objectionable disparity might turn out to be not objectionable once you discover what the systemic mechanism it’s actually generating it. Or it might turn out to be.

Typically, what you find is that it’s really mixed. If you take a typical example, Ibram Kendi in his How to Be an Antiracist book, which is hugely influential, is relentlessly focused just on outcomes as a way of establishing systemic racism. He gives the example of differences in homeownership rates between White and Black Americans but doesn’t say anything about what could be generating that. If you pop the hood on that and look and see what are some of the factors, what you discover is that, for example, the average age of Black Americans is 10 years younger than the average age of White Americans.

A certain fraction of the difference in outcome is going to be a product of this completely benign fact about the population groups, which is that Black Americans on average are significantly younger than White Americans. Now, of course, that’s not going to be the whole story, but that’s going to be a part of the story. You have to be willing to engage in it and to recognize that what looks like an injustice or like objectionable disparity might turn out to be at the very least more complicated.

SEAN SPEER: What is the consequence then of reframing how we think about the influence of institutional forces in impeding progress on certain social justice goals? How might it re-conceptualize the pursuit of such goals by placing a greater emphasis on institutional reform as a key precondition for progress?

JOSEPH HEATH: I do think that sometimes the constraints that arise from the contact with the real world of ideals is seen as being just a source of contamination that has to be resisted. In part, we have a moral ideal, and then we try to implement it, and it works out really badly. Then someone comes along and points out, says, “The reason it’s not working is because look at how people are acting, they’re acting in these ways that really defeat the purpose or that they’re ignoring the rules and pursuing their self-interest,” and so on. There’s a temptation to have a moralizing response and just to say people shouldn’t act that way, as though that’s the end of the discussion.

In a sense that’s hard to argue with, because of course it’s true, people shouldn’t act that way. If it’s persistent—like people act that way, and we’ve been trying for, say, 100 years to fix some problem, and people keep acting in a way that defeats a directly moralizing response to it, then we have to start thinking more creatively about ways to get around the fact that people act that way. I have a chapter in the book on border control and immigration. I think that when we—I’m a huge fan and proponent of Canadian multiculturalism, but I’m also someone who worries about it a lot.

Because I worry about the strains that high levels of immigration put upon society. Now, there’s a temptation to look at a lot of that. Those strains and those frustrations find expression in all kinds of different ways. One of the ways that they find expression is in the form of straightforward racism and xenophobia. Now, I think an unproductive way of responding to that is just to say, “That’s irrelevant because people shouldn’t be racist.” Which of course is true, but the fact is it’s a pretty solid 15 percent of the population consistently over time is racist.

One might also consider treating that as a sociological fact about the society that a certain relatively small, but not tiny, percentage of the population is going to be pretty xenophobic, and is going to feel really threatened. Then you might want to think about that as a kind of management problem, right? What do you do to make it so that that doesn’t contaminate public discourse, so that it doesn’t generate violence, so that it doesn’t generate the rise of an extreme right-wing party? In other words, you might think of it as a constraint on how we pursue immigration policy, not something that we just wish away.

SEAN SPEER: We’ll come to the essay on accommodation and pluralism because it’s chock full of insights. Before we get there, though I want to take up an institution that you’re well familiar with, the university, the modern university. You spend a lot of time on campus and have written about the cultural and ideological trends within these institutions, including the increasing tendency for HR departments to act in your words as “important vectors for illiberalism.” When these types of political forces grab hold of an institution, what can be done to repel them? How, in other words, Joseph, can universities protect themselves from these illiberal trends?

JOSEPH HEATH: The thing I worry about the most in Canada at the universities is what I refer to as cognitive capture by American public discourse in general. I actually spend a fair bit of time in the United States as well as in Canada. I think Canadians just consistently underestimate how different the United States is from Canada, and so there’s a huge tendency to just imagine that anything going on in the United States must also be going on in Canada, and that whatever kinds of problems Americans have must also be problems in Canada, et cetera.

I’ve argued in various public work that, for example, like the way Americans think about race is extremely unhelpful in a Canadian context. Simply because the whole history and situation in the United States is so different, but you’ve also got 90 percent of the Black American population have been in the country for five, six, seven, eight, nine generations. I’ve argued, for example, the situation with race in America is actually more similar to the situation with French Canadians and with Quebec in Canada. We are dealing with a national group that was involuntarily incorporated into the country.

You look at the situation of Black Canadians that is radically different from that. There’s a small population of African Canadians who are descendants of slavery, but the overwhelming majority, 90 percent, are first to second-generation immigrants. That gives them a lot more in common with people from India, people from China, and so forth. We have a radically different situation in Canada, and yet we often are trying, or we’re mindlessly adopting cultural templates from the United States. I was tempted to say we’re adopting solutions, but of course, we’re not even adopting a solution.

Because the United States, it’s not as though the American language of social justice has been successful at pacifying racial conflict in America. If anything, it’s a recipe for perpetuating racial conflict, and yet people are mindlessly adopting it. There’s been the same creep of this DEI thinking and so forth within Canadian universities as you’ve had in the United States. I think it’s perplexing in Canada for a different reason. The United States has got its own little argument going on. My basic concern within a Canadian context is it’s just inappropriate to the situation of Canadians.

For example, you see within that discourse, an enormous privileging of the concerns of Black Canadians, and given the pluralism that you see at universities like the University of Toronto, you can see for example, Muslims from Pakistan and so on, becoming quite irritated by the fact that many of these approaches and policies are arbitrarily privileging the interests of one class of immigrants over other immigrants, and other concerns that often seen as just as pressing, if not more pressing. What’s going on in the universities in Canada is very different from what’s going on in the United States, but one of the trends you see is just this failure to think about the specificities of the Canadian context.

SEAN SPEER: The book’s first essay talks about the issue of scale. It seems to me that one of the challenges of dealing with seemingly intractable problems like poverty or homelessness, or whatever, is that most effective interventions aren’t really scalable. They depend on contingent circumstances, including sometimes even the role of particular individuals. How should we think of the question of scale when it comes to cooperative solutions? What are some of the inherent limits on scale?

JOSEPH HEATH: The first chapter is called “On the Scalability of Cooperative Structures.” It references old debates about the feasibility of socialism, because most people, I think, are intuitive socialists. That is that our everyday intuitions are that the way in which we should cooperate with one another is that everyone should basically pitch in and do their part and that there should be a only limited role for self-interest and competition. So then if you go out into the world and you see how capitalism functions and it seems to be quite different from that.

There’s a huge role for competition and self-interest, and so people intuitively, morally, have difficulty reconciling themselves with the marketplace and its demands. A standard argument then, for the arrangement that we have is to say that the model where everyone just pitches in and does their part works well at a small scale, so with a group of roommates or people on a camping trip, stuff like that amongst friends, it may work out relatively well. Once you start adding more people, then increasingly antisocial motivations become more prominent, and therefore you have to reorganize things.

That reorganization then also requires a change in how we think about justice between individuals. The biggest change that occurs as what increases scale is that we have to rely more on extrinsic or external motivation rather than internal motivation. That’s a very neutral, philosophical way of saying that institutions have to become more coercive. So that when you have face-to-face interactions amongst people and people who are interacting with one another repeatedly, you could rely very heavily on people’s internalized moral constraint, sense of responsibility, and so forth to make sure that they don’t act in an anti-social way.

Whereas once relationships between individuals become more distant, so once I start interacting with strangers rather than people that I repeatedly interact with, then people start to act in a more self-interested fashion. Therefore, in order to maintain cooperation, you have to introduce more extrinsic motivation, and there have to be more punishments.

You can see this just by the way people behave in person versus once they get into a car. Think about how people manage a lineup at a movie theater where it’s face-to-face interaction, versus how we manage a merge on the QEW or something like that. That is in a highway merge, people are cutting line and acting in this completely anti-social way that you would never do that face-to-face because you would get confronted by the other people there.

That’s just a good illustration of how introducing social distance between people brings out more self-interested behaviour, and therefore you need to have traffic police enforcing laws and stuff like that. That point generalizes. Institutions become more coercive. When you think about morality and justice and what you can demand of people, then it changes the way you think about it in important ways.

Because when you think about the small face-to-face interactions, you can put pretty onerous demands on people because you’re not actually going to be enforcing them. You’re not going to be punishing people. You’re just going to be having conversations and saying, “I’m very disappointed in you.” Once you get larger scale institutions where you start introducing formal punishment systems, then you start having to think more carefully about what are you willing to actually punish people for doing?

The bar obviously has to be raised somewhat. Therefore the strictness of the moral obligations necessarily decline as we start associating punishments with them. So that’s part of what I want to capture in the book, is the way that it goes in two directions. It’s not just that the way we think about justice has to be that we have to think up institutions to implement our ideals. We also have to adjust those ideals in the light of how we implement them.

SEAN SPEER: That’s a great insight. I want to move to your discussion of capitalism if that’s okay. As a young person, I read Irving Kristol’s book, Two Cheers for Capitalism, in which he essentially argues that capitalism is a framework for organizing economic exchange, but it lacks an ethos or even an institutional character. You disagree. You make the case that the market economy is itself a large-scale institution. What do you mean and what are the implications of thinking about the economy as an institution rather than a series of decentralized transactions?

JOSEPH HEATH: One of the reasons to write is that you clarify your own thoughts. One of the things that I clarified for myself in a helpful way as I was writing those chapters was that what Adam Smith says about capitalism was, I think, the fundamental insight, which is that it’s a way of institutionalizing a division of labour, that’s what’s important about it. The reason it makes us richer is that the division of labour allows for specialization. As a result, I can spend my day doing philosophy while other people do things like make iPads and stuff like that.

So I get the benefits of all that specialization. The fact that I’m able to spend my day doing philosophy requires that thousands, perhaps millions of other people spend their days growing wheat and grinding it into flour, and making polyester for my shirt or whatever. All of the other necessities of life are being provided to me by other people. The right way to think about that, Adam Smith suggested, is basically as one big giant system of cooperation. We shouldn’t be thought of as a set of bilateral exchanges. The philosopher, Robert Nozick, famously compared a market economy to a marriage market and said people get married, it’s like people interacting with one another and we don’t worry about inequality in the outcome of the marriage market, so why should we worry about inequality in the outcome of the capitalist market?

The difference is that the marriage market is just two individuals pairing up, but they’re not all dependent upon each other. Even if nobody else got married, two people could still get married. Whereas the market is not like that. In order for you to do interviews and me to do philosophy, the two of us just can’t get together in a post-civilizational universe and do a podcast. There have to be millions of other people busy making food and heating our houses, and running the internet, and stuff like that.

Think of it as being a gigantic system of cooperation. Then I think that that’s the correct way of thinking about capitalism. Then of course the immediate question poses itself, if it’s a big system of cooperation, why is there all this competition? Why aren’t we just cooperating with each other? Then that’s when it gets interesting because that’s when you pop the hood and say, “why is it that we don’t just cooperate with each other”? That’s the basic socialist idea: if it’s a system of cooperation, we should just be cooperating. Then you have to get into a complicated explanation to say why you’re not doing it that way.

SEAN SPEER: Another of the collection’s essays defends the case for stigmatization. Why do you think stigma can be a useful social tool, and why do you think it’s fallen a bit out of favour? Or maybe, to put it more specifically, why do you think it’s come to be selectively applied?

JOSEPH HEATH: That paper stems from an interest that I have in self-control and self-control failure. In part because I think that it’s actually one of the deepest cleavages between Left and Right, which is that people on the Right want to explain a huge amount of whatever, social dysfunction or unhappiness, or inequality, as a consequence of self-control failure. In part, because of that, there’s an impulse on the Left that just deny that that’s what causes it. Just to deny the phenomenon.

If you look at an issue like say homelessness, someone from the political Right typically will look at that and they’ll say, underlying that is basically drug addiction or something like that. Some form of self-control failure. Or economic inequality, they say, “People are dropping out of school, having kids when they’re 15 years old. Those are all forms of self-control failure.” The Right likes to say that if you scratch the surface of any particular kind of social inequality, what you’ll find is self-inflicted misery.

I think that often the Left tries to respond to that by just refusing to treat it in those terms and say, “No, these are distributive justice issues. Look at how expensive houses are, that’s why there’s homelessness. Or, look at the incentives that people face in the workplace, that’s why they drop out of school,” and so on.

There’s a bit of a dialogue at the deaf there. I think that the Left sometimes therefore winds up just being in denial about fairly obvious phenomena, which is that people do ruin their lives in lots of different ways. It’s not difficult to elicit. Everybody knows this.

If I were to come up with a proposal—this is something Milton Friedman once suggested, he said, why do we make welfare payments once a month? Why don’t we just roll it into the tax system and you could just get a big payment in April along with your tax fund refund? You could just get your welfare for the year. Once a year payments of welfare. You say, what would be wrong with that? Everybody knows what would be wrong with that, which is that a huge number of people would spend all the money far too quickly and come January are going to be completely out of money. There’s a paternalistic aspect of the fact that we send out welfare cheques once a week. People are not very good at managing lump sums of money. The background concern is about self-control failure.

What I find is that in modern societies, as we get better at running social services and social safety nets, a lot of the misery that used to be due to objective circumstances and with recessions, and all these unexpected economic events that are completely outside of people’s control, increasingly we have insurance systems that protect people from that, and so if you look at the amount of misery and inequality that remains in society, an increasing fraction of it is actually caused by self-defeating behaviour and self-control failure.

I think that the Left needs to find a way of talking about that problem and figuring out how to adopt a progressive stance with respect to that problem, rather than implausibly denying its existence. The Right has adopted a highly moralizing and individualistic way of talking about it, mainly in terms of personal responsibility. It thinks that the appropriate response to self-control failure is to make sure that people basically bear the full costs of their bad choices. That, I think, in many circumstances winds up being inhumane, because the very fact that people are experiencing the self-control failure means that they’re not going to respond to these kinds of incentives that are being imposed upon them. It winds up just compounding their difficulties.

I think we need to find a more humane way and progressive way of thinking about self-control failure so that we can acknowledge that it’s actually a huge source of misery in our society. That’s what led me to talk about it. The question is that the—again one of the other dogmas that you find on the Left is just the denial that self-control failure occurs. Then the second is a general hostility to stigma in instances where individuals do suffer from self-control failure, and because it’s complicated, but the stigma is seen as being basically a punishment and it’s taken to be inappropriate to punish people for self-control failure.

My general concern with that is I think that it just hangs people out to dry in many circumstances because it winds up putting the onus—in a sense, in its own way it compounds the difficulty because it winds up putting the onus entirely on you to then overcome your self-control failure by eliminating some of the social structure and the consequences of failures of self-control. I want to rehabilitate stigma to a certain extent in order to argue that it does actually, in many cases, serves a useful social function.

There’s a good reason that we should stigmatize being a junkie. In part because it’s addictive. That is that you’re not just condemning somebody else’s lifestyle. A very large fraction of people who are addicted to opioids themselves want to quit. It’s not like it’s a direct expression of their considered view of the good life. The basic objection of stigmatizing it isn’t there. Then the real question is just what are the effects of stigmatization? Is it just adding insult to injury or does it actually serve a useful function in bootstrapping people’s efforts at self-control? I think we need to take that possibility more seriously.

SEAN SPEER: You also take up questions of pluralism and accommodation in the book, as we mentioned earlier. I want to ask you, Joseph, as countries like Canada become more heterogeneous and diverse, including with respect to conceptions of social justice or the common good, or whatever, is there a risk that cooperation becomes harder? How will multicultural societies work through these issues?

JOSEPH HEATH: There’s a chapter on immigration where I guess I use it as an opportunity to express certain kinds of anxieties. That is, certainly in the philosophical literature that I deal with, and what I argue with my colleagues at the University of Toronto, the general view is that because of the enormous economic inequalities between rich world and poor world, Canada and underdeveloped countries, that we have an obligation to maximize our intake of immigrants. The interesting question then becomes, I guess, subject to what constraints?

I pulled out some statistics that there are currently something like just shy of 1 billion people in the world today who would like to immigrate to another country. Of those people who want to move to another country, something like 80 million identifies Canada as their first choice of country to immigrate to. There are about 80 million people out there who want to move to Canada. Right away? I don’t know. That’s twice the population of the country at least. There’s a sense in which the view can’t be, “Let’s let in 80 million people right away.” There has to be something that constrains it. Now, then the question is how we should think about those constraints.

What I argue in that chapter is that in the background, there’s an unhelpful view that tends to think of the wealth of our nation as something like a big pile of money or something like that, or a big pile of resources that we’re sitting on, and then that’s what makes Canada wealthy. That’s not the view amongst economists. The first thing I do is just a little bit of an explanation about what it is that makes wealthy countries wealthy, because for the most part, out of these 80 million people that want to come to Canada, the fact that Canada’s a wealthy country has a huge amount to do with it.

Then the question is how does that work then? How do they come to share that wealth, and where does that wealth even come from in the first place? The way most economists think about this now is that what makes countries wealthy, or conversely what keeps them poor, is basically the quality of their institutions. The wealthy countries have an extremely effective system of cooperation such as a market economy, but they also have courts that are essentially non-corrupt and therefore contracts that can be enforced and property rights that can be enforced.

They have a government that’s relatively non-corrupt, so you can start a business without having to worry about predatory officials extorting all your money from you. You also have, for example, a currency that’s relatively stable, and a banking system that’s relatively stable so that you don’t feel like you need to spend your whole paycheque, but that if you save it, a couple of years later you can go and get your money out and spend it. That’s what generates investment, is the willingness to save rather than spend everything now.

There’s this huge range of institutions that make everything work nicely in such a way that we can become and remain a wealthy society, primarily by having a very advanced division of labour. There’s no question that Canada could have more people in it, but the reason people are coming is in part because they want to be integrated into the system of cooperation. The right way to be thinking about immigration is in terms of expanding the system of cooperation. This is where it connects up to the stuff I’m saying about scalability. What we’re really trying to do is scale up Canada, and then the question is what are the constraints on scaling up Canada? We’re exploring those constraints.

The number of immigrants that are coming to the country has gone up from 200,000 to 300,000 to now it looks like 500,000 a year. All of this is a little bit of an experiment to see how rapidly one can scale up a system of cooperation such as the one that we enjoy as Canadians. One of the points I want to make though is that it’s an experiment. In part, the government’s just guessing. It’s a little bit frightening the extent to which they’ve failed to articulate any sense of what the rationale is for the numbers that they’re coming up with on immigration.

Or the federal government has not been entirely persuasive that they’ve actually looked to see about what kinds of demands are going to be made on the housing market, on the health-care system, on the job market, et cetera. The way you should think about it is you’re trying to scale up a system of cooperation, and to do so as rapidly as possible to benefit as many people as possible. What I propose that is we need to start thinking more seriously about what the appropriate indices are to measure whether or not that scaling up is working well enough.

It’s naive to think that people are going to arrive in Canada and just instantly become Tim Horton’s Canadians. The enormous amount of research on this which has been shown that immigrants don’t just instantly re-optimize all of their behaviours as soon as they arrive in a new country, and in part because a liberal society is one that allows people to preserve a lot of their cultural and family practices, et cetera. There’s also a complicated learning process about how people discover which forms of behaviour are going to have to adapt, or which forms of behaviour are not going to have to adapt.

It’s a very, very long process of figuring out how do you act, how do you live in Canada, how do you enjoy living in Canada, what gets you in trouble, what doesn’t get you in trouble, and stuff like that. We need to think more seriously about how successful that mechanism is. I propose a variety of factors that we should be looking at to see whether or not we’re actually succeeding in scaling up our system of institutions, or whether we’re starting to incur a breakdown in those institutions. For example, even though it’s a conservative talking point, the fact is you should be looking at the crime rate.

Crime is a perfect example then of an institution which is starting to experience dissolution, where it’s failing to generate the appropriate levels of cooperativeness. If you’re getting large increases of crime across the board or in particular communities, then that’s a good reason to worry about it. The fact that we haven’t seen big spikes in crime is actually an important indicator that things are going well.

We still need to be keeping an eye on these things and we need to be always thinking about, what are we doing. We’re expanding the scale of an institution, and that’s hard to do. When you bring in 50-year-olds and say, now your life is going to be totally different and you’re going to have to act in a completely different way, that’s a wrenching transformation that people have to undergo. We should be thinking about whether that’s going well or poorly.

SEAN SPEER: That’s a brilliant answer, Joseph. It reminds me of your previous thinking of a more expansive conception of how economists typically talk about efficiency. That is to say, the optimal or most efficient immigration policy may not be merely about juicing GDP, but for accounting for these number of qualitative and quantitative dimensions that ultimately determine whether Canada is able to accommodate large-scale immigration without it resulting in negative economic and social consequences.

JOSEPH HEATH: One of the reasons I think that Canada’s done better on the immigration front than a lot of other countries in terms of not generating backlash or stuff like that is that the situation in Quebec is so unusual, that English Canada has learned a lot from what Quebec has learned about immigration. And so, when you think about it objectively, I think the English Canadians are not nearly sympathetic enough to the concerns that are expressed by Quebecers about immigration rates.

François Legault immediately, as soon as Trudeau announced his big immigration numbers, the premier of Quebec basically said forget about it. People were like, “Oh my God, they’re such racists in Quebec,” but you have to think about it from their perspective. People coming from all over the world, they’re moving to North America. They want to go and live in New York in the United States, but they couldn’t get in so they go to Canada instead. You wind up there in Canada and then all of a sudden you’re in this place called Montreal you’ve never heard of, and all of a sudden they’re telling you we don’t want your kids to learn English, we want you to learn French.

A typical immigrant’s going to look at that and say, “Why on earth when I moved to North America and learn neither English nor Spanish, but rather I’m going to learn French, and not even learn standard French, I’m going to learn a dialect of French that gets pretty persistently persecuted in France and outside of Quebec.” What Quebec is trying to do is something incredibly difficult, which is that they themselves are a minority and they’re trying to integrate immigrants into a minority culture rather than a majority culture. They have a pretty good index of whether it’s working well or not, which is language acquisition.

Are people actually learning French? They’ve gone through a long learning process. There’s a book that I read that I wish I could remember the name of but it was a former PQ politician who was actually of Hungarian ancestry. His family had immigrated to Quebec in the 1960s, so before Bill 101 and the attempt to get everyone to learn French. The policy that Quebec had was actually preposterous, which is that they had a Catholic school system that they basically excluded all immigrants from going to their school. He grew up in this Hungarian family in NDG, and he went to a high school where there was literally not one Quebecois student.

In fact, one year he has this little story about how one Quebecois kid came to the school. Everyone in the school referred to him as the Quebecois, because he was literally the only one in the school. Obviously, if that’s the arrangement where the school is 100 percent immigrants, how are they going to learn French? Obviously they’re not going to learn French because there’s literally nobody speaking French. They discovered that that was ridiculous, so they overnight switched to the opposite end, which is basically making everybody go to French school.

You can see how there has to be a critical mass. It’s absurd to think that anyone’s going to integrate into Quebec society when the kids go to a school with not a single member of the Quebecois population at that school. What percentage is the correct percentage? Do you need 30 percent, 70 percent, or 90 percent? There has to be something along those lines. Quebec, because they feel threatened and because their language, legitimately so, the language is in fact threatened, the way they’ve handled immigration has always had to be a lot more careful but also has been explicit.

There’s been a more informed discourse where people can articulate their concerns and then people can argue about it. For example, designating French as an official language is something that in Quebec doesn’t seem like a crazy thing to do. Then the flip side, then English Canada copies a lot of what Quebec does. We then declare English an official language. That actually goes some distance towards clarifying expectations. Now, of course, in the United States, they don’t do that. If you were to declare English an official language, that’s seen as an extreme right-wing backlash politics.

In Canada, it isn’t so much in part because it’s a matter of just mirroring what Quebec has done. I think the whole Quebec situation is super fascinating. We actually do learn a lot from it, although it doesn’t necessarily percolate into the public discourse. It’s one of the reasons why we’ve met—it’s because Quebecers treat their own culture as threatened that they therefore have responded to immigration in a more anxious, but nevertheless intelligent way.

I don’t think it’s wrong to always treat your culture as being, in principle, threatened. If 80 million people came to Canada, that would threaten their culture. It’s not the wrong way to think about it. You don’t want to be hysterical about it, but you nevertheless have to look at your culture and the system of cooperation that it generates as something that’s a little bit fragile that you want to preserve that as an accomplishment.

SEAN SPEER: Ton of insight there, Joseph. You’ve been so generous with your time. I want to just put one more question to you, and I’ll let you take it in any direction you want. It’s one that ever since we scheduled this conversation that I was keen to put it to you.

What do you think explains the growing interest on the intellectual Right in what is sometimes described as “post-liberalism”? How much of it do you think is attributable to liberalism being boring?

JOSEPH HEATH: [laughs] I guess I’m not entirely sure what you’re thinking of with post-liberalism. You mean liberalism in the American sense or in the global sense? Are you thinking of the worship of Orbán in Hungary and Putin, and stuff like that?

SEAN SPEER: Yes, exactly. That’s a political manifestation, but I’m thinking of scholars like Patrick Deneen at the University of Notre Dame or a group of intellectuals associated with the new upstart journal, Compact. They have come to reflect a growing sense that North American liberalism and pluralism lack a moral, and, in some cases, even theological foundation that is leading to a decline in virtue and moral living, and all the rest.

JOSEPH HEATH: That unfortunately has the primary effect is just to make me feel old, because this is the second iteration of this that I’ve seen in my lifetime. It’s the same thing with all of the woke stuff and all those arguments. It’s like my first reaction to that was like, “Oh, my God, it’s like the 1990s all over again. I’ve already seen this movie. I’ve already seen how it ends.”

Similarly, I actually grew up in the heyday of what was called the liberalism communitarianism controversy. I studied with Charles Taylor in McGill, who was one of the most prominent communitarians, and that was back when John Rawls was still alive, and Ronald Dworkin, all these great figures of 20th-century liberalism.

They had articulated this view about liberalism that said, “we’re just going to have principles that are going to be completely neutral with respect to your concept of the good life, and you can have whatever religion, have whatever you want in your communities, but the state is going to be neutral.” Then there was this communitarian backlash against it that said, “No, we need to have much, much stronger communities with shared values, the centre cannot hold,” all that kind of stuff. Charles Taylor had articulated a Canadian version of that idea, but you had something similar being said by Michael Sandel and Michael Walzer in the United States, and so on.

That debate blew over. In part, actually another Canadian, Will Kymlica at Queens University, was extremely influential in ending that debate. One of the ways he did so was by first of all showing that the liberal way of thinking about things, that is the desiccated, principled-based way of thinking about things, is really the only way of making sense of the ambitions of something like the multiculturalism policy, and also the forms of multinational accommodation that you get with, say, Quebecois, Indigenous peoples, and so on. Kymlicka provided this framework that adapted liberalism to show how that it could provide a principled and intelligent way of managing all these conflicts of pluralism.

You could get the concern for group difference that communitarianism had promised without abandoning a liberal framework. Then, meanwhile, the communitarian view really didn’t have anything to offer when it came to managing these kinds of pluralistic conflicts. If anything, it recommended a kind of libertarianism which is when you encounter people, if you want to preserve your big, thick moral community where everybody shares similar values, then you really can’t be letting in tons of immigrants and free thinkers, and stuff like that. You really need to just distance yourself from the people down the road. That liberalism communitarianism debate wound up resolving itself in part because you got the formulation of a version of liberalism that was really attractive and compelling.

When I listen to Deneen and so on, I find it’s just like a retread of that same argument, and I don’t see them bringing a lot of new resources to the table. I think that the interest in illiberal politics and in particular populist democracy that violates the rules of liberalism and using the power of the state to prosecute the culture war. You could only do that by violating certain norms of liberalism.

That’s new. That’s something you see on the American Right. You really don’t see it in Canada yet but you see it, say, with DeSantis in Florida. The idea that you’re actually going to use state power to try to win the argument against rights for gays and lesbians or something like that, that’s an imitation of illiberal populism. That’s not something that people were talking about in part of the 1990s, but at the conceptual and philosophical level, I don’t see a lot that’s new in the argument. That’s not just a repeat of the old argument.

There’s this persistent concern that liberalism fails to renew its own cultural foundations. That liberal societies consistently erode the thick community commitments that are required in order to socialize children to have them sufficiently well motivated to respect liberal norms. There is this self-cannibalism that takes place in liberal society. I guess all I can observe is that that’s something that people have been worried about for my entire lifetime. Fifty years have passed and it’s like theoretically still seems like a problem, but at the same time, 50 years have passed and the catastrophe that was predicted has yet to yet to appear. Take that for what it’s worth.

SEAN SPEER: [laughs] Those are tremendous insights, similar to the insights that listeners and readers will find in the book, Cooperation & Social Justice. Joseph Heath, thank you so much for joining us at Hub Dialogues.

JOSEPH HEATH: Yes, thanks for having me.