Months into the lockdowns that quickly followed the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, U.K. health minister Matt Hancock spoke for his counterparts across the world when he said he was tired of the “f—–g Sweden argument.”

As the rest of the world was imposing draconian lockdowns, Sweden was bucking the trend, imposing lighter restrictions and leaning towards recommendations and guidelines over laws.

Recently leaked WhatsApp messages revealed that Hancock even told his aides to bring him some easily digestible bullet points about “why Sweden is wrong” and the international press soon followed suit.

The New York Times described Sweden as a “pariah state” and other media organizations counted the “death toll” from the first wave of infections in the country. Politicians around the world, even then-U.S. president Donald Trump, warned about taking any advice from Swedish epidemiologists.

But with three years of distance from the early harrowing days of the pandemic and mountains of empirical data piling up, a new picture is starting to emerge. Some experts are arguing that Sweden had it right all along.

Adding up the numbers

A new report from the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, makes the case that Sweden has come out of the pandemic in better overall shape than almost all of Europe.

“One reason why Sweden got through the pandemic in a much better shape than many scholars, journalists, and politicians expected was that (these people) only thought in terms of strict government controls or business as usual. They failed to consider a third option: that people adapt voluntarily when they realize that lives are at stake,” writes Johan Norberg, the author of the Cato report.

A review of available data shows Sweden ranging from the middle of the pack to best in Europe on most indicators, and massively over-performing the dire predictions from experts predicting tens of thousands of deaths in Sweden during the first few months of the pandemic.

In terms of cumulative COVID-19 deaths, Sweden ended up in the middle of the pack in Europe with 2,322 COVID-19 deaths per million people.

That compares favourably to the United States and the United Kingdom, both of which suffered more than 3,300 deaths per million people, and unfavourably to other Nordic countries, which were all below 2,000 deaths per million people.

Those numbers are tough to compare because countries count these deaths differently. Norway, for example, only counted COVID-19 deaths if the virus was the primary cause of death. In Sweden, anyone who died while positive for COVID-19 was counted.

According to self-reported data on excess deaths, which count the number of deaths that occurred compared to a normal year and which is a better comparison, Sweden leads Europe with an excess death rate of 4.4 percent for the three-year period from 2020 to 2022.

Italy, which suffered from an early and traumatic wave of infections early in 2020 reported a three-year excess death of 12.3 percent. France’s rate was 9.2 percent, Germany’s was 8.6 percent, and Norway’s was 5 percent. The average rate in Europe was 11.1 percent.

Even among excess death calculations from other sources that use different time frames, the results are broadly similar, with the Nordic countries clustering at the bottom of the chart and Sweden among them.

The economy and schools stayed open

Sweden also bucked the global trends on education and the economy, which was one of the primary arguments used to support the country’s approach to the pandemic.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development reported that the global economy was nearly three percent smaller than expected in 2021, while the Eurozone was 2.1 percent smaller. In Sweden, where the economy is export dependent and vulnerable to global downturns, the economy was still 0.4 percent bigger than expected in 2021.

While North American schoolchildren suffered significant learning loss after enduring virtual education during waves of infections, a recent study found that Swedish children are on track when it comes to literacy metrics and concluded that “open schools benefitted Swedish primary school students.”

And while research has shown that American kids fell behind on their regular vaccinations when the focus in health care shifted to COVID-19 in 2020, the vaccination rate for Swedish children was actually up in 2020.

How did Sweden do it?

The question of how and why Sweden managed to buck the global trends on pandemic response has several answers.

Sweden’s early spike of infections resulted in a wave of critical press from around the world but, according to cumulative COVID-19 statistics, most countries that imposed harsh lockdowns seem to have only delayed those deaths.

Sweden’s excess death rate spiked in 2020, as the virus swept through nursing homes in the country. By 2022, the numbers had levelled out as the omicron variant of the virus blanketed the globe.

“The other countries managed to delay some deaths, but now, three years after, we end up at around the same place,” said Preben Aavitsland, a Norwegian epidemiologist.

Although some press reports suggested that Swedish decision-makers regretted the path the country took, it wasn’t actually the case.

“It’s not like that at all, we still think the strategy is good, but there are always improvements you can make, especially when you have the benefit of hindsight,” said Anders Tegnell, Sweden’s state epidemiologist, in response to these reports.

Tegnell said that, in retrospect, he would have done more to protect nursing homes and provide testing kits.

Norberg, the author of the Cato report, argued that Sweden’s unique division of power when it comes to governmental agencies may have been a key factor.

The directors-general of these agencies are independent of the government and have set terms, meaning they aren’t replaced when the government changes. It’s extremely rare for the government to replace the head of one of these agencies before the term ends.

It gives the agencies more power and, Norberg argues, it also gives the politicians an alibi if the advice is controversial.

Perhaps easier to explain is the intense backlash against the Swedish model, as illustrated by Hancock’s WhatsApp messages and angry outburst about the “f—–g Sweden argument.”

Aavitsland, the Norwegian epidemiologist, argues that Sweden’s method became a cudgel against politicians and health experts who were under intense pressure during a global crisis.

“Sweden became the contrast they did not want. Sweden undermined their mantra that we had no choice and forced them to explain to their citizens why they did what they did,” said Aavitsland.

“For these colleagues, it would have been better if everyone had done the same. They hid their own insecurities by lambasting Sweden.”

Recommended for You

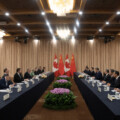

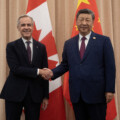

‘Canadians don’t trust China’: Hub Politics on the risks and rewards of Carney’s China trip

‘Bending the knee’: Former Canadian ambassador on Prime Minister Carney’s misguided trip to China

‘A politically motivated prosecution’: Did Donald Trump just declare war on the U.S. Federal Reserve?

As First Nations, we must stop waiting on Ottawa and start working towards our dreams