There are precious few things everyone can agree on these days, but $10-a-day child care appears to be one of them.

As The Hub’s Geoff Russ wrote last month, the Liberal plan for Canada-wide $10-a-day child care is here to stay after legislation enshrining the program was adopted unanimously by the House of Commons.

“With a single vote… the Conservative Party seemed to end two decades of opposition to a national child care program,” wrote Russ. Russ noted that repealing national child care is no longer a “credible” option for Conservatives.

With $10-a-day child care all but inevitable, provincial governments would be well advised to study the documented shortcomings of the universal, flat-fee model of child care and plan accordingly.

Quebec’s universal child care program, which has been a fixture in La Belle province for the past quarter century, has dominated the national conversation on child care. While the program has its strengths, it has also drawn widespread criticism for perpetuating disparities in access to quality child care along socioeconomic lines. A recent audit conducted by the province’s auditor general found that nearly half of children enrolled in Montreal’s highly coveted Centres de la Petite Enfance (CPEs) came from households making $200,000 per year or more. The same study found that there was one CPE space for every three eligible children in the tony neighbourhood of Westmount and just one space for every seven children in the working-class borough of Montréal-Nord.

Less well-studied has been British Columbia’s half-decade-long experiment with $10-a-day child care. B.C. launched the first pilot study of the program in the fall of 2018 and, since then, has opened over 12,700 $10-a-day spaces, accounting for roughly ten percent of all regulated child care spaces in the province. This gives B.C. a sizeable head-start over most other provinces.

Unfortunately, there are already signs that B.C. is falling into the same equity trap as Quebec.

How $10-a-day child care works in B.C.

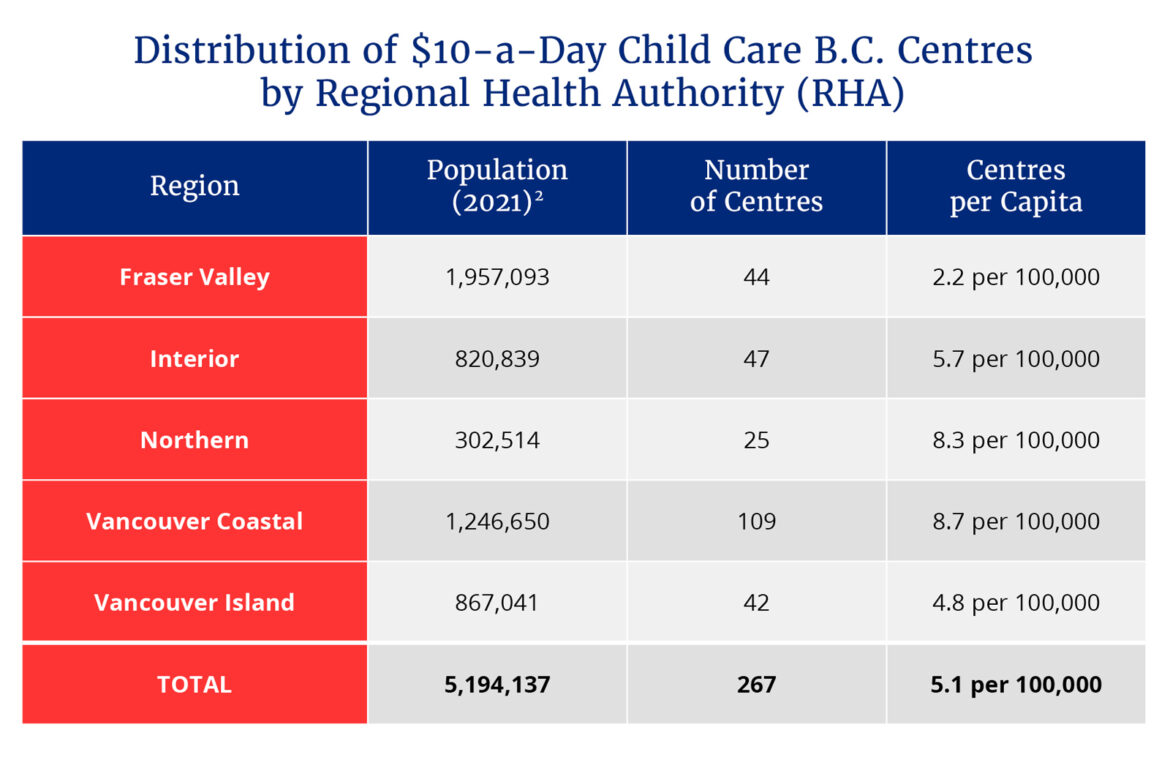

B.C.’s Ministry of Education and Child Care presides over a network of some 267 $10-a-day ChildcareBC centres. Nine in 10 centres in the network are administered by either non-profit groups or public institutions (i.e.: schools and universities). On average, each centre serves roughly 50 children.

Licensed child care operators apply directly to the Ministry to become $10-a-day centres. Successful applicants receive funding from the Province to cover operating expenses, minus the $10-a-day parental fee collected by the centre itself. The Ministry received more than 600 applications during the 2021-22 expansion of the program, approving just a handful.

Where are $10-a-day centres located?

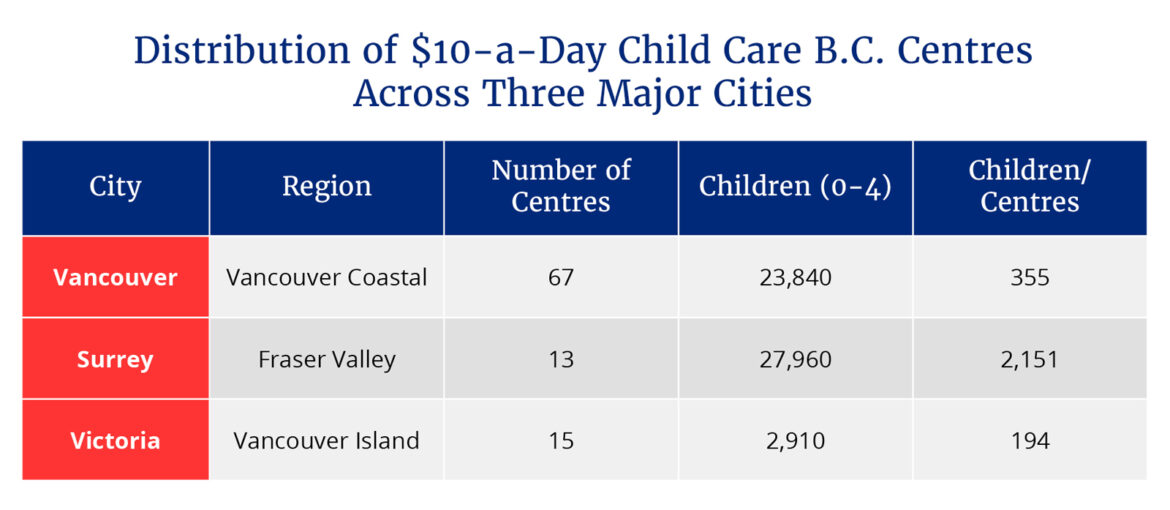

One glance at the current list of $10-a-day centres reveals clear regional disparities in where centres are located. Notably, Vancouver is home to more than five times the number of centres as Surrey, despite the latter having a larger population of eligible children. Heck, even the province’s capital city of Victoria has more centres than Surrey, despite having one-tenth the number of children. (I guess the province’s politicians and bureaucrats need somewhere to park their brats during the workday).

Combined, the Vancouver Coastal and Vancouver Island regions are home to over half of B.C.’s $10-a-day centres, despite making up just forty percent of the province’s population. Meanwhile, the heavily populated Fraser Valley boasts just two centres for every 100,000 residents.

The Ministry of Education and Child Care has acknowledged this problem and has stated it will prioritize communities with a “low proportion of $10-a-day spaces compared to population density” in future application cycles. Whether it will follow through on this promise remains to be seen.

Are $ 10-a-day centres concentrated in rich neighbourhoods?

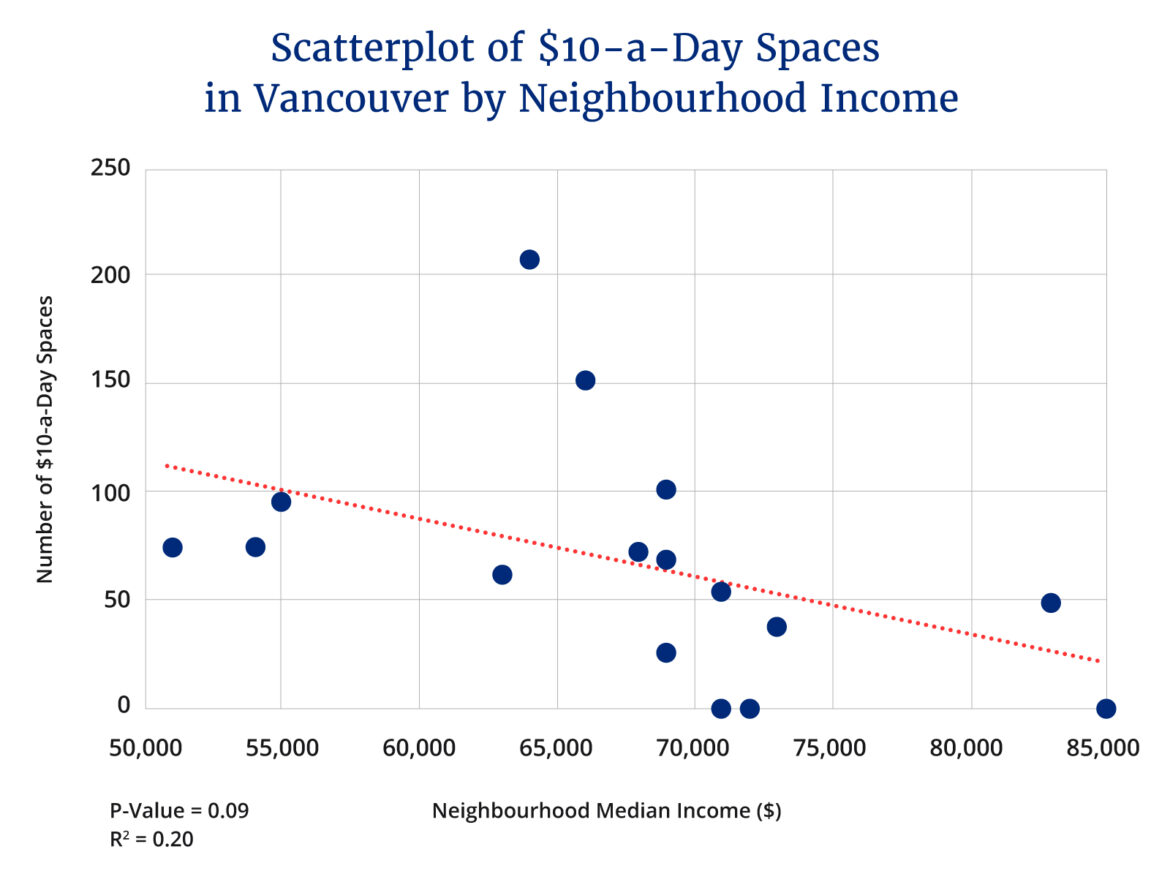

The good news is that, based on neighbourhood-level data I collected from Vancouver, there’s little evidence of an income-based disparity in access to $10-a-day child care. There is, in fact, a negative correlation between neighbourhood median income and $10-a-day child care spaces. This relationship maintains statistical significance even when Vancouver’s troubled Downtown Eastside (DTES) is dropped from the sample of neighbourhoods. On average, each $10,000 drop in neighbourhood income is associated with 26.5 additional spaces (figure excludes DTES).

This is not to say that the distribution of spaces across Vancouver is totally equitable. The two parts of the city with the highest concentration of spaces are the downtown business district and the University of British Columbia endowment lands (both are home to 14 $10-a-day centres). Together, these two areas soak up four-in-10 of the city’s $10-a-day spaces.

Given Quebec’s experience, it’s not surprising to see centres cluster in parts of the city with high concentrations of white-collar professionals (e.g.: office workers, university faculty). This indicates that, barring offsetting social policies, relatively well-off urban professionals are the group most likely to benefit from the Canada-wide rollout of $10-a-day child care.

What can provincial governments do about this?

With Canada-wide $10-a-day child care now a fait accompli, provincial governments should act now to pre-empt the likely regressive effects of the program. Policymakers should accordingly consider adopting the following policies:

- Cash subsidies for alternative care in regions with low concentrations of $10-a-day centres: As B.C.’s experience indicates, there are likely to be marked regional disparities in the rollout of $10-a-day child care. It could take years for these disparities to balance out. In the meantime, provincial authorities should offer cash to subsidize alternative child-care arrangements (e.g.: at-home care, relative care) in underserved areas.

- Reserve a quota of spaces for 24-hour centres and centres located in low population-density areas: White-collar urban professionals who work conventional nine-to-five schedules shouldn’t be the only parents to benefit from $10-a-day child care. Policymakers should keep the needs of parents with irregular work schedules, as well as those who live outside of urban cores, in mind when choosing where to open new $10-a-day sites.

Recommended for You

Scandalous politicians could finally face serious consequences if this Supreme Court case is won, says democracy watchdog

Don’t downplay the costs of the AI revolution: The Weekly Wrap

Jewish groups advocate for new hate crime laws and better police tools to punish perpetrators

‘It’s in the Liberals’ interest’: The Roundtable on whether Trump’s antics will trigger an early election