- Canada's debt-to-GDP ratio significantly increased following the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The government argues that a decreasing debt-to-GDP ratio indicates fiscal sustainability.

- Critics contend that inflation and immigration are driving GDP growth, masking underlying economic issues.

- Provincial debt is a crucial factor often overlooked when assessing Canada's overall fiscal health.

- Rising interest rates pose a challenge, increasing the cost of servicing Canada's debt.

- Experts disagree on whether Canada's current fiscal path is sustainable in the long term.

Canadians are stressed about the economy. You don’t need mountains of polling data to figure that out. But dig into the work of Canada’s pollsters and you’ll find only 14 percent of people say they are better off financially than they were a year ago and, even worse than that, many Canadians don’t see any relief on the horizon. What can we do about this? In this five-part Hub series, we’re digging deeper into the economy, identifying our country’s fiscal problems, but also offering solutions to our monetary malaise.

Part 1: Independent or not, groupthink might be the Bank of Canada’s worst enemy

Part 2: Is Canada’s real estate-driven economy dragging down growth?

Canada’s fiscal books in the last decade can be divided between two starkly different eras: pre-pandemic and post-pandemic.

The pre-pandemic fiscal situation in Canada was a time of calm finance ministers and debt ratios that gave Canadians bragging rights among OECD countries. Post-pandemic? Well, let’s just say it got a little ugly.

Prior to the pandemic in 2018, the federal government’s net debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 29.2 percent, the lowest among the G7 countries. By 2020, that percentage had ballooned to 68.7 percent due to emergency spending during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The federal deficit for 2019 stood at 1.8 percent of nominal GDP, and 14.8 percent in 2020.

The government, and its supporters, insist that Canada is on a healthy fiscal path. Critics point to bursting balance sheets, previously unseen amounts of red ink, and soaring inflation. So who’s right?

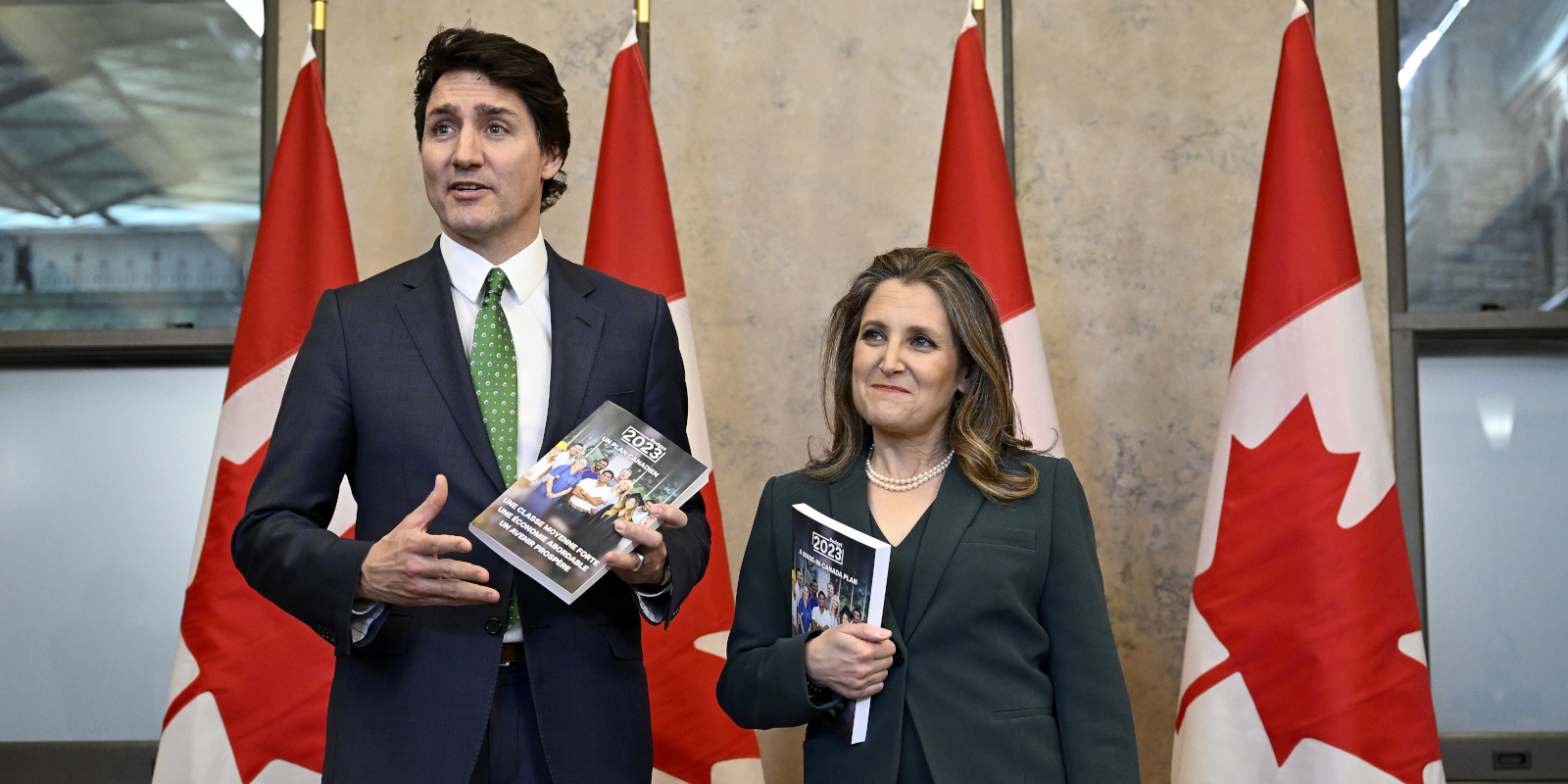

Although Prime Minister Justin Trudeau came to power in 2015 publicly touting a higher tolerance for budget deficits, the initial plan was to bring the country back into balance. Soon, the government found a new “fiscal anchor” and has argued that as long as the debt-to-GDP ratio continues to drop, the country is in good shape.

In 2022’s first quarter, the net debt-to-GDP ratio, minus its financial assets, had fallen to 56.8 percent. Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland has used that reduction as a way to reassure financial markets of Canada’s fiscal sustainability.

However, many critics question the Liberal government’s rhetoric on its fiscal record, including some who formerly worked in it, like Robert Asselin, the Business Council of Canada’s senior vice-president and former budget and policy director for Freeland’s predecessor Bill Morneau.

While noting that economists generally agree that a country’s debt-to-GDP ratio being reduced over time means its fiscal situation is sustainable, Asselin says the current situation is more complicated than that, and that reducing debt due to emergency spending is easier than paying off other debt.

“Our nominal GDP is going up right now for two reasons. First is we have high inflation, which boosts our revenues and the supply of money we have in the economy,” says Asselin. “Second, we are admitting a lot of immigrants. And this is a good thing that we’re admitting a lot of immigrants to the country and, just as a function of the number of workers, nominal GDP will come up.”

Others like Dave Rosenberg, founder and president of Rosenberg Research, believe immigration will be a key contributor to Canada’s growth outpacing rising debt.

“There is nothing that stops Canada’s growth from out-running the growth of debt in the context of how the government is sharply stimulating the supply side of the economy through its aggressive immigration policy,” says Rosenberg.

However, Asselin says this does not mean Canada’s economy is growing in a healthy way, and says GDP-per-capita has been stagnant and is now declining.

Canada’s per-capita output in 2022 was about the same as in 2017 and is expected to decline for the next two years according to the Bank of Canada. In 2021, an OECD report projected that Canada will be the worst-performing advanced economy in the world for the next four decades.

However, Rosenberg believes Canada is not in the worst place when it comes to fiscal policy.

“Canada’s debt-to-GDP ratio may well be the cleanest shirt in the dirty laundry basket, and that indeed is due to much lower leverage in the corporate sector. And believe it or not, the government sector is also in relatively better shape,” says Rosenberg.

Provincial debt adds up

Vincent Geloso, an assistant professor of economics at George Mason University and a senior economist and director with the Montreal Economic Institute, says comparing Canada’s net debt-to-GDP ratio to peer countries is simply obfuscation.

“I’m sorry, if I get to be a fatty and I go to a restaurant and I eat 50 pounds of steak and I say, ‘Not as bad as the guy who eats 75 pounds,’ it’s not a great comparison,” says Geloso.

Geloso says that once Canada’s subnational debt is brought into the equation, the country is in a much weaker fiscal position. Canada’s net debt-to-GDP ratio does not account for the gargantuan amount of debt incurred by Canada’s different provincial governments.

“The provinces are spending a lot and it’s not that surprising…if you run through what provincial governments do,” says Geloso, pointing out that the provinces are responsible for areas like health care and education.

Canada’s gross debt-to-GDP ratio, as opposed to net debt-to-GDP, includes all the subnational debt of all its provinces, territories, and local governments.

“Sometimes people look at the federal government finances, and they say, ‘Canada looks like they’re in pretty good shape in terms of budget balance and debt,’” says Brendan La Cerda, an associate director and senior economist with Moody’s Analytics. “When you add in the provincial debt…that healthy fiscal picture for Canada disappears, and all of a sudden, Canada’s debt-to-GDP ratio is actually about the same as the U.K.’s.”

In the third quarter of 2022, the U.K.’s total government debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 100.2 percent, while Canada’s gross debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 117.2 percent in 2021.

Don’t take it for granted

Tyler Meredith, who served as Trudeau’s economic advisor, before co-founding Meredith Boessenkool Policy Advisors, says that whether by the federal government’s metrics or those of international organizations like the IMF, Canada is in the best fiscal position of the G7, and one of its only member countries to maintain a AAA international credit rating.

“When the IMF assesses other countries and tries to create comparable indicators…it does take a certain proxy of provincial accounts…I could go on a fair bit of differences in accounting about things like social security payments and stuff like that,” says Meredith. “But for the most part, the short story…I think is that Canada has the smallest deficit at the federal level as a share of GDP, and the smallest debt as a share of GDP at the federal level as well.”

But in many of these rankings, the provincial debt is not factored into the equation, which is something that bothers Asselin.

“One thing that bugs me in this debate is that a lot of people are using net debt when they compare Canada,” says Asselin. “On the net debt metric, Canada looks okay, but I think when you look at gross debt, with everything included in them, we are probably much worse than a lot of the OECD countries, actually I would say below the average.”

According to the OECD’s latest data, Canada had a far higher gross debt-to-GDP ratio in 2022, 113 percent, than the OECD average of 90 percent. It is a higher gross debt-to-GDP ratio than countries with comparable standards of living like Israel and Austria, or countries with a lower standard like Brazil and Hungary.

“The markets, right now, are not worried about Canada, but that could become (so) if we keep spending and not being responsible. So I don’t think one should take this for granted,” says Asselin.

Meredith says that when assessing Canada’s fiscal situation, people should look to international debt rating agencies, where he says there is a strong appreciation for the Canadian government’s positions.

“I don’t just mean that as a partisan thing. I think Canadians should feel comfortable that we have an enviable fiscal position,” says Meredith, who says it doesn’t mean that Canada should not always be looking for efficiencies and improvements.

Who backstops the provinces?

La Cerda does not believe that offloading major costs to the provinces to reduce the country’s net debt entails any benefits, and instead, creates more problems. He says that because subnational governments cannot issue their own currency, a higher share of Canadian provincial debt is denominated in foreign currencies.

“The reason they do that is to make it more attractive to international investors,” says La Cerda. “So creating this schism between federal debt and provincial debt, it almost creates more complications than it is worth. Because at the end of the day, the federal government has to implicitly guarantee that debt.”

Geloso says that because the provinces are essentially creations of the federal government, somebody will have to pay up if a province defaults, and that to a certain degree, the federal government should be expected to step in if that occurs. He points out that a condition demanded by Prince Edward Island for joining Confederation in 1864 was that the federal government assume responsibility for the then-colony’s debt.

“If it’s a small province again, like Prince Edward Island…..I don’t think it would be a dramatic story for the whole of Canada,” says Geloso “But if provinces like Ontario go into default range, some, you could say, unorthodox economic policy might become necessary. That would mean, for example, playing with monetary policy to deflate the real value of these debts, essentially.”

Geloso says other options would be “crash course” austerity that entails aggressive spending cuts across the board without much consideration of how to do it or the consequences.

“That probably would be somewhat problematic,” says Geloso.

The interest rate crunch

La Cerda says the main fiscal challenge for Canada is dealing with the massive amount of debt-spending during the pandemic and the consequences of that.

“We’re entering an environment with higher interest rates, and that’s going to increase the government interest rate expenses, and we’re gonna have a larger portion of the federal budget getting eaten up by those interest expenses,” says La Cerda.

Asselin says that people can often think governments don’t have to repay their debt, but they actually do always have to keep (de)financing their debt on financial markets.

“When interest rates rise, the cost of that debt servicing is higher, as we’ve seen over the last year, and so the implication of this is very simple: the more you pay to service your debt, the less revenue you have to finance other priorities,” says Asselin.

The interest expenses accrued from Canada’s total debt cost $64.6 billion between Ottawa and the provinces in 2021, or 6.8 cents on every dollar. Currently, the federal government is projected to spend $49.1 billion in the 2022-2023 fiscal year on the Canadian Health Transfer, which is the annual transfer payment provided by Ottawa to the provinces for health care.

“If the argument is that it’s okay to pay as much on debt-servicing that you transfer to provinces (for health care), then I think people have to start asking some questions, especially given how much we’re funding health care in this country,” says Asselin.

The health transfer is expected to rise to $54 billion in 2023-24. The total cost of the Canadian health-care system is about $330 billion per year, roughly a quarter of the total of Canada’s public debt, and the system is regarded as one of the most inefficient among its peer countries.

Asselin says that while Canada is unlikely to end up in a scenario where it becomes a regular recipient of IMF loans, that is not how he would define sustainability.

“For me, sustainability is when the revenues you collect are sufficient to finance the programs and the promises you’ve made to Canadians,” says Asselin. “If they are not, then I think over time, they will become unsustainable.”

How does Canada's debt-to-GDP ratio compare to other developed nations, and why is there debate over which metric to use?

With rising interest rates and a significant portion of the budget going to debt servicing, what are the potential consequences for government programs and priorities?

How might immigration and inflation be impacting Canada's GDP, and are these factors necessarily indicative of a healthy, sustainable economy?

Recommended for You

Why the world needs even more Canadian coal

Are Vancouver property rights really at risk? Law professor raises questions after federal government-First Nation deal in B.C.

‘Triple-digit pricing is entirely possible’: How will the Iran war affect global energy prices?

Have Alberta’s finances gone off the rails?