The Hub’s first annual Hunter Prize for Public Policy, generously supported by the Hunter Family Foundation, focused on solving the problem of long wait times in Canada’s health-care system. A diverse group of ten finalists have been chosen from nearly 200 entries, with the finalists and winners chosen by an esteemed panel of judges, including Robert Asselin, Dr. Adam Kassam, Amanda Lang, Karen Restoule, and Trevor Tombe. The Hub is pleased to run essays from each finalist this week that lay out their plans to help solve this persistent policy problem. The winners of the first-ever Hunter Prize for Public Policy will be announced on Friday, September 29.

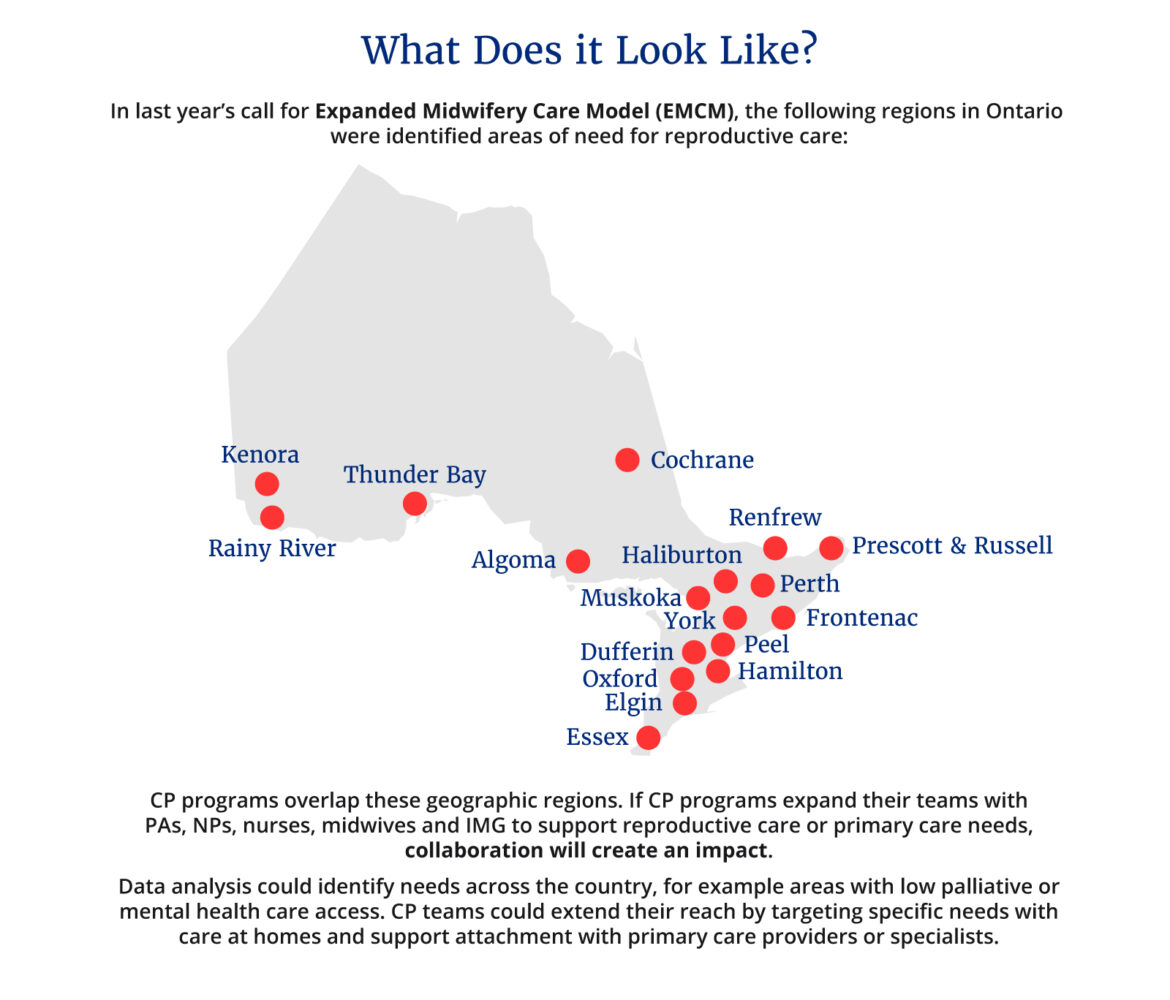

As a midwife and member of the sandwich generation, I have my share of opinions about the current state of the health system. One way to address ER wait times is to expand community paramedicine (CP) programs into interdisciplinary teams that provide home visits, and link community and hospital settings, noting that the majority of pre-COVID home visits in Ontario by doctors were for home-bound patients, older adults, primary care (e.g. ear infections), and palliative care patients. Additional data on reproductive health shows gaps for this population as well.

After a deep dive into the research to prepare my briefing, there are a few resources that I wanted to highlight here that anchor my experiences and insights.

I wasn’t surprised at the identified priorities in this recent report from CIHI. However, delays in the emergency room (ER) need to be addressed differently than delays in the operating room (OR), and not to mention delays in diagnostic services that contribute to bottlenecks in both services. Flashback to a month ago, my mother-in-law woke up in pain, and off to the ER she went. She needed surgery and was transferred to another hospital to wait for surgery. For her, the lasting memory of this experience was the pain. “Unbearable”, she confessed, until IV antibiotics were administered almost 24 hours after arriving at the ER.

When the dust settled, I was disheartened to realize that I could have alleviated my mother-in-law’s discomfort myself, much faster as my midwifery colleagues and I have frequently administered IV medications at home. To make such a plan feasible though, I would need to refresh my knowledge and supplies to monitor patients like her at home. Some CP programs in Canada also offer IV antibiotics at home.

During the pandemic, staff were deployed wherever there was a need, demonstrating that it is possible to upskill health-care workers quickly to address urgent health concerns. Interdisciplinary teams offered insight and contributed to knowledge exchange and transfer to bolster the pandemic responses in several provinces. Despite the ability of front-line workers to be agile and adapt, it became frustrating to serve when directives lacked evidence or were disconnected from the realities of people’s lived experiences.

Programs to increase the reach of nursing, physician extenders, pharmacy, and midwifery colleagues are being implemented in various forms across the country to maximize patient care and experience. International medical graduates (IMG) are underused resources, a missed opportunity to arrive at feasible solutions to past and current delays in health. If political leadership can procure funding from tight budgets to expand programs and scope of practice, there can be policy solutions and funding that can make better use of IMGs.

Funding cross-training using existing resources can quickly expand the capacity of Community Paramedicine (CP) to meet a wider community need. Training includes traditional and experiential learning which is well suited for adult learners. Overall, CP programs are making a difference in their community, and contributing well during the health human resources (HHR crisis), particularly for older adults and palliation, in urban, rural, and remote areas.

Reproductive health often straddles primary and specialist care, as well as community and hospital settings. Midwifery programs also offer additional training to upskill workers in reproductive health. For example, ultrasounds during pregnancy, contraception, or assisting in surgeries. As the Ontario Midwifery Program, 2022 states:

Currently pregnancy and newborn care is primarily provided in a ‘stand alone’ model outside of comprehensive primary care, often resulting in multiple transfers of care and/or uncoordinated care from multiple providers.

Expanding CP into interdisciplinary teams that are embedded in hospital systems is having an impact. Scaling these models by training and hiring interdisciplinary care providers will better manage crisis states such as wait times, but also long-term goals for population health. However, there is limited evidence relating to the impact of CP on surgical delays, as it likely hasn’t been done but is ripe for innovation.

Not everyone has a fixed address or feels reassured at home. As it is, most people default to the ER when faced with a health event. Rapid enrollment to the CP pathway can offer care at home and better allocate the resources of the trauma team while also serving patient needs.

Federal transfer payments for health support regional variation in addressing community needs. Technology, training, and personnel exist that can be leveraged in CP expansion. CP teams may help out in the ER for the short term but others may need multiple teams, but why reinvent the wheel? Sharing models and experiences will support stakeholders to implement and expand impactful interventions. Better collaboration with front-line workers and patient advisors will align mandates from policymakers to allocate funds to regional efforts.

During the pandemic, we often failed to return to the roots of population health management. Specifically, what does it mean to improve the nation’s health? Health disparities, poorer health, and mental health challenges make it harder to keep the health-care system operating during short-term stresses like the pandemic, as well as maintain long-term sustainability. Overall progress in core public health functions will support upstream and downstream interventions to address health delays. Valuing public health across the health ecosystem is critical to address the current crisis.

Ultimately, policymakers need to be willing to do their part to make it easier for patients, families, and care providers to take the lead in prioritizing solutions. Specifically, policy expertise will reduce barriers to entry in complex systems. Too often, med-tech interventions that can improve health system performance rely on accelerators and incubators, funding for innovative ideas in health care, and funding to commercialize. Really, a collaborative culture, from policymakers all the way to patients and providers, should surround a publicly-funded health system to address problems but also optimize health.

Recommended for You

Daniel Zekveld: Age verification for pornography is not government overreach

DeepDive: Under pressure: How immigration is becoming a political fault line in Canada

Andrew Leslie: A bold step forward for Canada’s defence

Renze Nauta: Nearly seven million Canadians are in the working class. Their growing struggles deserve the spotlight