Usually we think of history as the story of what actually happened. Yet, as historian Niall Ferguson recently argued in a podcast, another way of thinking about history can be found in “trying to remind yourself again and again that what happened, that what we know happened, might have gone the other way.”

This process of counterfactual analysis, as Ferguson noted, allows us to think about the contingencies of history: that is events that could have plausibly gone a different direction than they did and, in that one change, a whole series of events would have been unfolded differently.

To illustrate his point, he offered the dramatic example of the decision of the U.K. cabinet to enter World War I, which was the key factor in turning that conflict from another continental war into a world war. Ferguson noted that at the time it was not taken for granted that the British cabinet would in fact choose to join the war, and if it had not, the history of the 20th century would have been significantly altered.

Canadian history may, at first glance, appear to not be fertile ground for counterfactuals given it lacks some of the drama that popular counterfactuals are often built around. Yet there are undoubtedly key moments where Canadian history turned even though people at the time may not have realized it.

One such moment occurred on an evening in Ottawa 43 years ago last month. On December 13, 1979, MPs gathered in the House of Commons to vote on the first budget of Joe Clark’s young government.

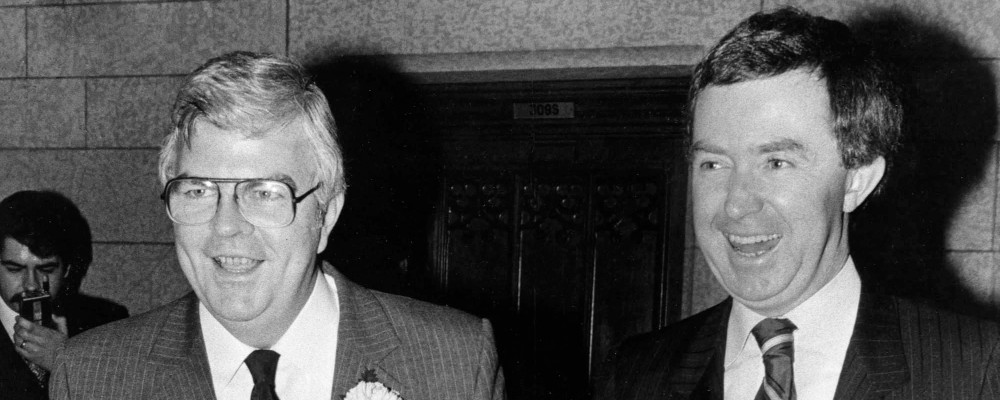

John Crosbie, Clark’s finance minister, had tabled a budget which sought to demonstrate a new note of fiscal responsibility with limited new spending and a hike to the gas tax but was not well received by the public. Sensing an opportunity, the Liberals pulled out all the stops to get their MPs to the Chamber that evening leading to an unusual level of suspense about the outcome. The final tally was 139 Nays to 133 Yeas with five MPs abstaining. Joe Clark’s government had fallen a little more than six months after it was sworn in.

In the campaign that followed, Pierre Trudeau emerged victorious and moved back into 24 Sussex. Rather than rest on his laurels, the next four years cemented much of what is remembered of the Trudeau legacy. It’s fair to say that, in many ways, we’re still living in the world that was set in motion during the Trudeau government’s subsequent term.

That legacy first and foremost being the 1982 repatriation of the Canadian Constitution, which most notably included the creation of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This term also saw the creation of the National Energy Program, to much unhappiness in Alberta, and the federalist victory in the first referendum on independence in Quebec. While this was a productive term, it also left the Liberals deeply unpopular, as John Turner discovered upon succeeding Trudeau. So in some sense, the Mulroney government that followed was also part of the legacy of the final Trudeau term.

However, all of this could have been very different. A few weeks before the 1979 vote, Pierre Trudeau had announced he would leave the Liberal leadership once a leadership contest could be held, and the party had started planning for his succession. Had the PC government survived that vote and lasted even a few more months, Pierre Trudeau would not have led the Liberals into the campaign and thus never returned as PM.

As this never happened we can never fully know what this alternative history would have looked like, so some caution is required when engaging in the not entirely scientific practice of counterfactual history. But it seems undeniable that had the Clark government won that vote, the last 43 years of Canadian history would have some distinct differences.

This is most clearly seen in the patriation of the Constitution. This was a particular passion project of Trudeau which he had tried and failed to achieve in his first round in office as he could not get a consensus among the premiers. Rather than be discouraged by the challenges of finding agreement, Trudeau returned to office prepared to spend enormous political capital and hardball tactics to make it happen. It is far from certain that another PM from either the PCs or Liberals would have been so committed to constitutional reform. There was no grand popular demand for constitutional reform. The deal happened because Trudeau was willing to go to great effort in outmaneuvering his foes in the provinces.

No constitutional deal means no Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the accompanying judicial revolution that followed. As The Hub has recently reflected on, the Charter has so massively reshaped Canadian law and policy that it is hard to imagine Canada without it. But it can too easy to miss the degree to which the Charter and the entire patriation project required Trudeau’s will to make it happen.

While the impact of the deal is most felt in the impact the Charter has had on our laws, it had implications in many other ways. For instance, the final deal was famously done without the participation of Rene Levesque who was surprised to learn that Trudeau was willing to cut a deal without Quebec. What Trudeau may not have realized (or cared about) is that doing so would help shatter the Liberal’s dominance of Quebec. From 1891 up to the 1980 election the Liberals won a majority of the seats in Quebec in all but two elections, frequently dominating the seat count in the province (in 1980 they took 74 of 75). In the 12 elections that followed the Liberals have won a majority of Quebec seats only once, by a narrow margin in 2015.

The National Energy Program is another big what-if. It is unlikely that the Clark government, with so many of its MPs from Western Canada, would have enacted such a program. The NEP in the West and the repatriation in Quebec both contributed to disillusionment with Ottawa in the East and West. This first benefited Mulroney as it swept him to power, and then it helped to tear his party apart, resulting in the rise of both the Reform Party and the Bloc Quebecois.

On the other hand, some major developments may well have happened even if Trudeau had not returned to power, such as the free trade deal with the U.S. While John Turner offered voracious opposition to the deal, Mulroney adopted free trade at the recommendation of the Macdonald Commission which was established by the subsequent Trudeau government. The namesake of the Macdonald Commission was Donald Stovel Macdonald, a long-time Liberal cabinet minister who was the favorite to succeed Trudeau as Liberal leader in the leadership contest that was cancelled in 1979. Had he succeeded Trudeau as Liberal leader and won the next election, perhaps it would have been his government rather than Mulroney who made a deal with the U.S.

Or alternatively, a longer-lasting Clark government may have launched free trade talks given another early champion of the idea was Finance Minister John Crosbie (who was ironically attacked by Mulroney for proposing the idea in the 1983 PC leadership race.)

The impact of a Trudeauless 1980s on other events is harder to know. For instance, the 1980 Quebec referendum saw the Yes side lose by nearly 20 percent. It’s possible the result would have been similar under a Clark government. But, on the other hand, having Trudeau and his top lieutenant, Jean Chretien, at the top of the government was a major challenge to the Yes argument that Quebec needed independence to have power. In contrast, despite Clark’s best efforts, the PC government was thin on Quebec representation with only two Quebec MPs and 13.5 percent of the popular vote in Quebec. If the PQ had had Clark as a foil during the referendum campaign, it is possible that the dynamic of the campaign would have been different and the result could have been different as well.

Of course, this all leads to the question: is it plausible to think PCs could have won the 1979 vote? That night there were 136 PC MPs to 114 Liberals, 27 NDP, and 5 Social Credit serving in the House. With Liberal James Jerome serving as Speaker, that meant the Liberal/NDP MPs had a maximum of 140 votes. If the PCs and Social Credit voted together, they would have 142 votes.

The Social Credit MPs had been trying to convince the PCs to give them some concessions in order to get their support for the budget. The Clark government may have assumed that the Social Credit MPs had no choice but to support the PCs given an election would not be in their best interests. And given that the 1980 election saw the entire Social Credit caucus defeated and the party disappeared from the political scene, this was not entirely wrong analysis. But in the moment, it was not so great as a tactical assumption.

However, given that the final count was 139 Nays to 133 Yeas, even if the five Social Credits MPs had been enticed to vote in favour, the government still would have fallen thanks to three missing PC MPs who were absent due to illness or ministerial travel. Unlike the Liberals who went to extreme lengths to get all their members to the vote, the PCs had two ministers away travelling on the day of the vote. Clark and his cabinet appeared to have been operating on an assumption that a defeat would see Canadians rally to the newly elected government and turn the minority into a majority as John Diefenbaker did in 1958.

This assumption was clearly faulty in retrospect but it was also pretty dubious at the time given there was little evidence in public polling that the voters were excited by what they were seeing in the Clark government. This also gets to one of the challenges of this counterfactual: if the PCs were capable of recognizing the risks of a loss and avoiding it, they may also simply have been better at politics overall and thus more likely to win the election when it did happen.

Since we cannot go back and redo that vote we’ll never be able to be certain of what may have happened. Yet it is still a useful thought experiment because it helps to illustrates the ways in which history is highly contingent. While it is undoubtedly clear that the world in which Clark and Crosbie won the parliamentary vote would have in large part produced a similar to the one we live in, it is a reminder that the tides of history are less certain than we sometimes imagine, which is a reason to take the choices before us a little more seriously.

Recommended for You

Crystal Smith and Eva Clayton: Indigenous natural resources development is an efficient, fair, and responsible way to advance economic reconciliation

Peter Menzies: Justin Trudeau’s legislative legacy is still haunting the Liberals

‘There are consequences to this legislation’: Michael Geist on why the Canada-U.S. digital services tax dustup was a long time coming

Rudyard Griffiths and Sean Speer: The future of news in Canada: A call for rethinking public subsidies