Noah Smith, an economist whose commentary I always find original and insightful, wrote a great commentary earlier this week on why China’s industrial policy has been mostly a flop. His main argument—which I very much agree with—is that throwing a lot of public money at firms is the wrong and ineffective way to do industrial policy.

The current debate around—and the application of—modern industrial policy is a topical and consequential one. As far back as April 2020, in “A New North Star II“, Sean Speer and I argued the Washington Consensus that emerged in the 1980s—centered on “free” markets, liberal trade, and open capital markets—was going to be challenged in a significant way by growing geopolitical rivalries and an increasingly intangible economy. Three years later, the policy debate in most Western countries is now not about whether industrial strategies should be adopted or put forward, but how big these public investments should be.

To us, though, the issue was never about how much we should spend, but rather how we ought to spend. In a late 2021 paper, for instance, we argued for significant institutional reforms to Canada’s science and technology architecture including a new agency with a specialized staff and a high degree of autonomy so as to minimize the risks of bureaucratic inertia and political capture.

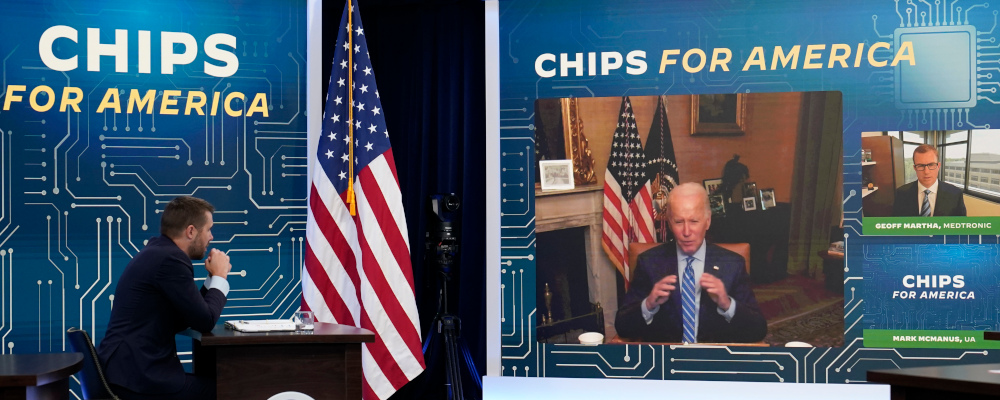

The urgency to for Canadian policymakers to adjust their thinking to these new economic and geopolitical realities has only been heightened. The passage of the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act in the U.S. last spring was a game-changer. With investments cumulating nearly USD $460 billion, it is, in constant dollars, almost double what the U.S. government spent in the 1960s on the entire Apollo space program. With the U.S. also in discussions with key allies to restrict semiconductors exports to certain markets, it’s clear just how much the new geopolitical rivalries are reshaping economic policymaking and the global trading system. Technological innovation and national security are now inextricably linked.

In a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed, JP Morgan Chase & Co.’s Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon—one of America’s strongest champions of free enterprise—wrote:

Global trade will necessarily be restructured so that we don’t rely on potential adversaries for critical goods and services. This will require more ‘industrial planning’ than America is used to—and we must ensure it is properly done and is not used for political purposes…Most developing countries would prefer to align economically with the West if we help them solve their problems. We should develop a new strategic and economic framework to make ourselves their partner of choice.

Dimon’s warning is prescient. It is an unfortunate reality that the historic philosophical debate on the role of the state in the economy is being used by some as a policy and political wedge. After all, markets and governments are not operating in two distinct parallel universes. The demarcation between state intervention and laissez-faire is rarely clear-cut.

I would argue, for example, that an aggressive economic immigration strategy is a very effective industrial policy instrument. Talent nurtures innovation and innovation increases productivity. It’s a rising tide that lifts all boats. But very few would think about economic immigration as an obvious case of government overreach in a market-driven economy. Every country needs and has an immigration policy and its outcomes are a reflection of policy choices rather than spontaneous forces.

The debate on industrial policy is thus not about whether we need a lot of government intervention or no intervention at all. Instead, it should be about its effectiveness: that is how industrial strategies are designed and what policy instruments are used to achieve them.

From my perspective, this is where governments fall short.

The legitimate and valid arguments against industrial policy

1. Lack of clear objectives: Too often governments confuse industrial policy with the politics of “job creation” or “regional development” or any number of priorities that detract from core goals of innovation and productivity. Political capture is an obvious danger and politicians will often be tempted to promote industries of their liking and influence outcomes to their political favour.

Unless we set higher productivity and economic competitiveness as clear goals for an industrial policy, vague objectives are bound to yield underwhelming results. In a recent Public Policy Forum paper I argued that the modern application of science and technology is the new frontier of economic competitiveness and, as a consequence, Canada needs to urgently rethink its science and technology architecture. In a recent speech at MIT, U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo presented a clear, concise, and comprehensive articulation of the American game plan that starkly defines its economic priorities:

We believe there are three families of technologies that will be of particular importance over the coming decade: first, computing-related technologies, including microelectronics, quantum information systems and artificial intelligence; second, biotechnologies and biomanufacturing; and third, clean energy technologies.

2. Overreach and overregulation: Overshadowing market dynamism and entrepreneurial impulses harm economic outcomes. An economy that is overregulated is bound to be less competitive. As the Obama administration’s Strategy for American Innovation rightly noted:

The true choice in innovation is not between government and no government, but about the right type of government involvement in support of innovations. The private sector should lead on innovation, but in an era of fierce global competition, governments can and should play an important enabling role in supporting private-sector innovation initiatives.

Creating the right macroeconomic conditions conducive to capital formation is paramount. This includes the regulatory environment and tax policy.

3. Implementation and execution: At a time when we witness governments struggle to deliver the most basic services for citizens—renewing a passport, receiving health care, etc.—it is only fair to ask whether governments have to ability to formulate and deliver industrial strategies that can be effective. The design and implementation of policy instruments (such as tax incentives, R&D funding, and demand-side levers such as public procurement) requires a degree of sophistication and thoughtfulness. When the right structures and incentives are put in place, the evidence shows that success is possible.

The shaky arguments against industrial policy

If some arguments against industrial policy are valid, others are easier to dismiss.

1. The free-market argument: There is a somewhat romantic and prevailing view amongst certain economists, columnists, and policymakers that market fundamentalism—laissez-faire economics inspired by a caricature of Adam Smith’s “invisible hand”—is supreme. Under this ideological bent, free markets’ “efficiency” is everything we should aim for. The problem, of course, is we all know markets have never really been “free” and “efficient”, nor will they ever be in the future. In his BBC Reith Lectures in 2020, Mark Carney offered a powerful demonstration of how market fundamentalists have failed to recognize that the economy isn’t “deterministic.” As he astutely pointed out, in any given market competition is never perfect, and consumers and market players are not rational actors. Markets are always constrained and shaped by regulations, competition policy, or tax policy, and, yes, by trade and industrial policy.

I underline this not to undermine the value of economic theory, but to infuse some pragmatism in the current conversation on industrial policy. To state the obvious, the idea that the market is always right is fundamentally flawed. If this was true, as Carney rightfully observed, it would have been easy to prevent the great financial crisis of 2008 that caused millions of Americans so much economic hardship.

2. Industrial policy is central planning of the economy (the China model): Another common criticism of industrial policy is that it consists of “central economic planning” and even amounts to essentially adopting the Chinese model in Canada and elsewhere. Yet in liberal capitalist economies, even if industrial policy is solving for market failures (e.g., climate change) or prioritizing national security issues (e.g., biomedicine or semiconductors) the ultimate investment, innovation and production is still being driven by the private sector. In China, by contrast, there is essentially no private sector in China. Everything is state driven. The comparison is absurd.

3. Industrial policy equals “subsidies”: As I expressed up front, I agree giving subsidies to private firms is the wrong way to do industrial policy. But there is a certain intellectual laziness—or a fair amount of bad faith—by those who keep portraying industrial policy exclusively as “subsidies”. An equivalent assertion would be to say tariffs equate trade policy. It’s one (mostly negative) feature of trade policy but it’s not all of it. When I think about industrial policy and where it needs to go, I reflect on the immense economic successes of the Apollo Program, the ARPA model of funding breakthrough research in the United States, and the Fraunhofer institutes in Germany. I think about South Korea and what they did in advanced manufacturing or how the Netherlands, a country about half the size of New Brunswick, became an ag-food powerhouse.

These are compelling models of public-private collaborations that have yielded significant productivity enhancement for national economies. Policy design and policy instruments matter a great deal. A May 2022 OECD paper on the effectiveness of certain policy instruments used in industrial strategies concluded that some are quite effective.

4. Governments don’t know how to pick winners: It’s certainly true that they don’t at the firm level. But people adopting this line of argument miss the larger point: yes, the sectoral composition of an economy matters a great deal.

As our economy suffers from a chronic lack of productivity and our trade deficit is in danger of becoming structural, the capacity of our economy to produce goods and services becomes paramount. Canada has become a services/real estate economy. We have lost significant manufacturing capacity since the 1970s. In 2020, for instance, residential investment represented 37.2 percent of gross fixed capital formation.

In Potato Chips, Semiconductor Chips: Yes, there is a difference, Rob Atkinson makes a strong case for that not all sectors are equal when it comes to industrial policy. His main point is that some industries, such as semiconductor microprocessors (computer chips) can experience very rapid growth and reductions in cost, spark the development of related industries, and increase the productivity of other sectors of the economy. There are, in other words, certain sectors or productive capacities that are worth having in one’s economy and justify using public policy in order to cultivate. As Atkinson puts it: “In essence, spillover effects from computer chips make potato chip manufacturers more efficient. In addition, jobs producing computer chips have higher productivity and require a higher skill level and thus pay more than jobs producing potato chips.“

As for the trade deficit, by the time the pandemic hit, Canada had recorded 11 consecutive years of current account deficits. As David Dodge stated in a PPF paper: “The current account deficits can also be seen as the inevitable product of Canadians and their governments choosing to borrow to maintain a high level of private and public consumption rather than finding ways to generate national income through added production.”

The question then becomes: how best can a government support these types of advanced and more productive industries? I agree subsidies to firms is not the way to go. This is why focusing on how you translate public R&D into economic outputs must become a clear economic imperative.

Again, the examples of the Netherlands in ag-tech, Germany in advanced manufacturing, and the United States in defence and space in fostering industrial public-private R&D at scale and commercializing speak volumes. I have argued elsewhere that Canada needs, as a key component in an industrial strategy, a modern incarnation of what used to be corporate labs—where industrial research done in collaboration between governments, universities, and businesses led to real innovation at scale in the economy.

In his new book, Slouching Towards Utopia, economic historian J. Bradford DeLong writes:

What changed after 1870 was that the most advanced North American economies had invented invention. They had invented not just textile machinery and railroads, but also the industrial lab and the forms of bureaucracy that gave rise to the large corporation. Thereafter, what was invented in the industrial research labs could be deployed at national or continental scale. Perhaps, most importantly, these economies discovered that there was a great deal of money to be made and satisfaction to be earned by not just inventing better ways of doing old things but inventing brand-new things.

A final point: democratic governments are bound to make decisions on what they believe is best for the voters they are elected to represent. Our parliament has passed net-zero legislation. We’ve effectively set a political economy goal that markets alone won’t solve for because of the uncertainty and the risks involved. One can argue, I suppose, that we shouldn’t set such political economy goals and that what we produce, buy, and sell should be left fully to market forces. But no economy in the world operates that way or has ever operated that way.

And so, from time to time, we are going to have political economy goals that go beyond what the market will produce on its own. In these instances, we need to think carefully about how to incentivize the market to do what is required for the public good. That will necessarily involve some form of industrial policy.

Recommended for You

A rocky road for Ontario, and an unconventional CUSMA renegotiation: The Hub predicts 2026

Poilievre will survive as CPC leader, and Canada will stay golden in men’s hockey: The Hub predicts 2026

Supply management will be sacrificed to appease Trump, and the Netflix takeover is bad for Hollywood: The Hub predicts 2026

Canada will attempt to join the EU and Justin Trudeau becomes a Katy Perry lyric: The Hub predicts 2026