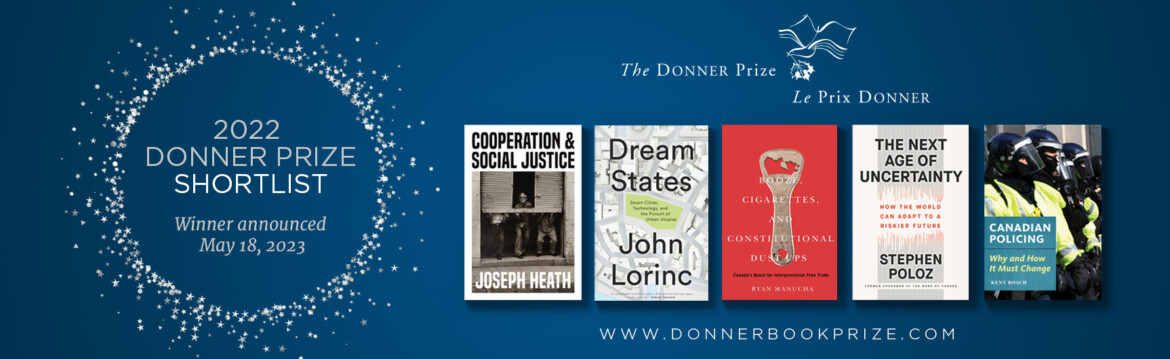

The Hub is proud to be partnering with the Donner Prize, which will be announced on May 18. We’ll be running excerpts from the shortlisted books all week and you can also listen to Hub Dialogues episodes with all the nominees. Click here to view the shortlist and get caught up on Canada’s best public policy books.

Extract from Canadian Policing: Why and How It Must Change by Kent Roach

Kent Roach a professor at University of Toronto Faculty of Law, was elected to the Royal Society of Canada in 2002, awarded the Molson Prize for contributions to social sciences and humanities in 2017 and appointed to the Order of Canada in 2017. His numerous books have won dozens of awards. He has served on a number of commissions of inquiry including the Maher Arar, Ipperwash, Air India and Goudge inquiries.

Winnipeg police officer Robert Chrismas has observed that police officers can face “quadruple jeopardy” for alleged acts of misconduct. He has a point. Police involvement in death and serious injury can be subject to independent criminal investigations. It can also be subject to civil and Charter litigation, public complaints, and disciplinary processes. As Ian D. Scott, the former head of Ontario’s Special Investigations Unit (SIU), has written, “there would appear to be massive duplication” in multiple proceedings arising from the same event, but all of these different proceedings “engage different social objectives.” In an attempt to respond to overpolicing, the police are subject to more complex and lengthy forms of accountability than ever before.

At the same time, police are often not found liable, especially in criminal prosecutions. The police, better than most other suspects, know when to “lawyer up” and exercise their right to silence. Police unions have talented lawyers on speed dial to help defend officers. Those lawyers can place victims of police violence on trial with self-defence and other claims. They can bring preliminary motions to wear down those who bring civil lawsuits. And when all else fails, they can settle lawsuits on a confidential basis.

When the police are held liable, the public often concludes that they receive light penalties. Courts can exclude evidence because of Charter violations without officers being disciplined or policies being changed. Disciplinary penalties often involve temporary demotions and/or docking of pay or days off. The often-mild outcomes of all of this hyperaccountability help explain why 73 percent of respondents in a September 2020 poll believed that the police are not held accountable when they abuse their power.

Increasing penalties for police misconduct may not, however, be the answer. The police will, if anything, even more vigorously resist accountability measures if the penalties are higher. Higher penalties for overly aggressive policing could result in overdeterrence, “depolicing,” or risk-averse policing that could result in more underprotection.

Review of police conduct is required by the rule of law. The police are the only civil servants who routinely carry guns. At the same time, Canada’s legalized system of hyper-accountability seems not to be improving policing. It does not seem to be diminishing repetitive acts of aggressive overpolicing or underprotection examined in the last chapter…. One explanation for repetitive acts of overpolicing and underprotection is that police are too often left to govern themselves without clear or firm political direction. The police defend self-governance on the basis that they are independent from political direction in all operational matters. They rely on legal arguments and their expertise to fend off what they claim is “political interference.”

Effective and proactive governance—not after-the-fact hyperaccountability—is necessary to improve policing….A factor that contributes to the undergovernance of the Canadian police is divided jurisdiction over all forms of policing. The provinces enact policing acts. They set and enforce adequacy standards, whereas local police boards establish police policies and local councils approve police budgets. When the now-retired mayors of both Calgary and Edmonton showed some attraction to policing innovations in 2020, Alberta’s minister of justice sternly warned them that the province could intervene and even take over city policing if reallocation of dwindling revenues led to a breach of provincial adequacy standards. When Toronto City Council tried to influence the policies of the Toronto police in June 2020, it had to ask the province to give them powers to review line budget items in the more than $1 billion a year that it provides to the Toronto police. It also unsuccessfully asked the province to remove the ability of the police to appeal cuts to their budget to the province.

The democratic governance of the police is a fundamental constitutional issue. As Justice Dennis O’Connor has stated when examining the review of RCMP national security activities, Canada could become a police state if the government could order “the police to investigate, arrest or charge—or not to investigate, arrest or charge—any particular person.” At the same time, “complete independence,” or self-governance of the police, “would run the risk of creating another type of police state, one in which the police would be answerable to no one.”The answer to this dilemma is to codify police independence over law enforcement decisions in individual cases and require all directives on policing operations and policies to be made public.

Divided jurisdiction over policing is a hard reality of Canadian federalism and the precarious nature of local government. It presents challenges to unified and active governance of the police. Local governance of the police may be an ideal, but it is complicated by the provincial role in local policing and the federal role in the RCMP’s contract policing. When it comes to policing failures, it is easier for each level of government to point their fingers at each other. Whoever governs the police needs proper education about their role, the police, and community safety issues. They need to listen to those who are policed as well as to the police. They need to be concerned with both the efficacy, including cost-effectiveness, and the propriety of policing.

Perhaps the time has come to follow the recent English practice of having local voters elect police and crime commissioners who can devote all of their energies to such matters. Committees of local council may also be in a better position than police boards to make decisions about how the police should work with other public agencies responsible for health, family services, housing, and education. Because they fund the local police, local councils may be in a better position than boards to ensure that the police provide value for money. As will be seen in the next chapter, police budgets have grown more quickly over the last thirty years than other public expenditures.

Recommended for You

Peter Menzies: Justin Trudeau’s legislative legacy is still haunting the Liberals

‘Our role is to ask uncomfortable questions’: The Full Press on why transgender issues are the third rail of Canadian journalism

Need to Know: Mark Carney’s digital services tax disaster

Theo Argitis: Carney is dismantling Trudeau’s tax legacy. How will he pay for his plan?