The saintly editors here at The Hub have agreed to my request to produce one of my two monthly articles for the site as a monthly transatlantic diary. For those readers not familiar with the format, which is more common in British journalism, the diary is a grab bag of short items, sometimes on a common theme, but often not. In my case, what they have in common is that they are either too inconsequential to merit a full article or I can’t be bothered to come up with more than a knee-jerk reaction or a flip comment. This is June.

Canada was well-represented in the old country this past month as King Charles III took his birthday salute astride Noble, a black mare gifted to him by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. It was the first time the monarch had ridden for the Trooping the Colour since the Queen rode her own beloved RCMP horse, Burmese, in 1986. Burmese famously acquitted herself well at the Trooping the Colour in 1981, when a mentally-addled teenager fired six blanks at Her Majesty from a replica revolver. A trained police horse, Burmese calmly carried the Queen to safety as the Household Cavalry closed ranks and the parade continued uninterrupted. Noble has a ways to go to match her late compatriot’s sangfroid, as she appeared rattled by the large crowd lining the Mall and several times the King had to bend low and whisper soothing words. Her occasional skittishness aside, visiting Canadians were able to cheer a new Canadian King on a new Canadian mount. It is good to see any tradition continue, but this one was especially poignant.

***

As it happened, I was in town that day, but not for Trooping the Colour. I had popped down to order summer shirts and meet friends for lunch. It was one of those days that makes one instantly regret being in a city. Every stone and pavement had absorbed the bright sunshine and I was assailed by cloying heat from all sides. Lunch was at Andrew Edmunds, one of the few places in London that still offers honest food, a fairly-priced wine list, and relaxed charm but has not fallen prey to “influencers.” I am confident that anyone filming a TikTok would be promptly and not-so-politely asked to leave, if not by the owners then by their fellow diners. Unfortunately, the restaurant is also small, and while this is a cosy blessing in the winter, on this day it meant three large men were squeezed into a window seat while the bright sun glared mercilessly through the glass. A bottle of cool white burgundy fairly evaporated in our glasses, though that probably can’t be blamed on the sun. As enjoyable as lunch was, it was a relief to get back to the bosky North Oxford shade by evening.

***

A flying visit to Paris to see my sister and nephews took me to the Jacquemart-André to see the Giovanni Bellini exhibit. A few years ago I saw the spectacular Caravaggio exhibit there—easily one of the three best exhibits I’ve been to— and while the Bellini did not quite meet that impossible standard, it was a sensitively-chosen and thoughtfully-paced selection, without a single superfluous piece and including several outright masterpieces. In other words, it is what one would expect from that gem of a museum. Highlights were the Dead Christ Supported by Two Angels from the Gemäldegalerie and Mantegna’s Ecce Homo from their own collection. When we got home, the nephew who accompanied me was inspired to get out his paints, which is all one can ask of such a visit. The nephew had been before (to the museum, not the exhibit) for a classmate’s birthday, and was excited to show me the tail of a monkey that extends out of the trompe l’oeil mural on the café ceiling. There are, I reflected, obvious benefits to a Paris childhood.

I forget how it came up, but at some point in our conversation my sister mentioned that the boys were not allowed by French law to have social media accounts. I looked this up later and it’s true: last year, France passed a law barring children under 13 from having social media accounts and requiring children under 15 to have parental permission. The ages are still too low—I’d set the ban at 18 regardless of parental indulgence—but at least the government is doing something. I read somewhere that the French laws passed with unanimous support in the National Assembly, while here in Canada, not a single party is even proposing to protect children from Big Tech’s predations. Researching the French restrictions, I also learned that France requires proof of age to access pornographic sites, which is another no-brainer on which Canadian legislators are dragging their feet, though at least it is on or near the agenda. This seems like a good opportunity to leverage the blessed discipline of stigma for the common good: which party is going to take a stand for the commercial interests of online pornographers?

***

Back in Oxford, June saw the election of a new Oxford Professor of Poetry, which was quite exciting for the sort of person who gets quite excited about that sort of thing. The post is a prestigious one, having been held by some of the great names of English (and non-English) letters, including Matthew Arnold, Cecil Day-Lewis, WH Auden, Robert Graves, and Seamus Heaney. A quick perusal of the full list since 1708, however, reveals that these luminaries are very much the exception. Some of the older names that are remembered at all are remembered for something other than their poetry. How many who admire the ornate brickwork of Keble College still read John Keble’s cycle of devotional poetry, The Christian Year? And if anyone reads Maurice Bowra’s verse today, it is likely to be the scurrilous and scatological stuff that used to circulate privately among tittering dons. Nevertheless, the role is, as I said, prestigious, so much so that candidates campaign for it, sometimes crookedly. During the 2009 election, Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott withdrew after rumours of sexual harassment were spread by supporters of rival candidate, Ruth Padel. Whether Padel knew or approved of these tactics remains unclear, but in any event she resigned after only nine days. For her sacrifice, Padel was appointed Professor of Poetry at King’s College London; Walcott, for his sins, was exiled to the University of Alberta.

This year’s election was scandal-free. The favourite (as far as one can tell in these things) was the Scottish poet Don Paterson, but my vote was for Mark Ford. I backed Ford not for his poetry, which I like just fine but not as well as Paterson’s, but because he is one of the great contemporary expositors of poetry for a general audience. Notwithstanding the implications of the title, the Oxford Professor of Poetry is not required either to teach or to compose poetry; his main task is to deliver 12 public lectures, one each term for four years. Ford’s essays in the London Review of Books and the New York Review of Books are models of the style, and so I voted in anticipation of his lecture series. Although Ford was not elected, I am not displeased with the actual winner, AE Stallings. She is a lively poet whose work is formally sound. It is also often classically themed, which befits someone who lives full-time in Athens, though she will have to work hard to match the classical eccentricity of the very first Oxford Professor of Poetry, Joseph Trapp, who was reportedly fond of extemporising Shakespeare’s verse in Latin. Now that’s a party trick.

***

With the end of the month approaching, it was back home for Dominion Day, Stampede, and the permanent charivari of Canadian politics, about which more next month.

Recommended for You

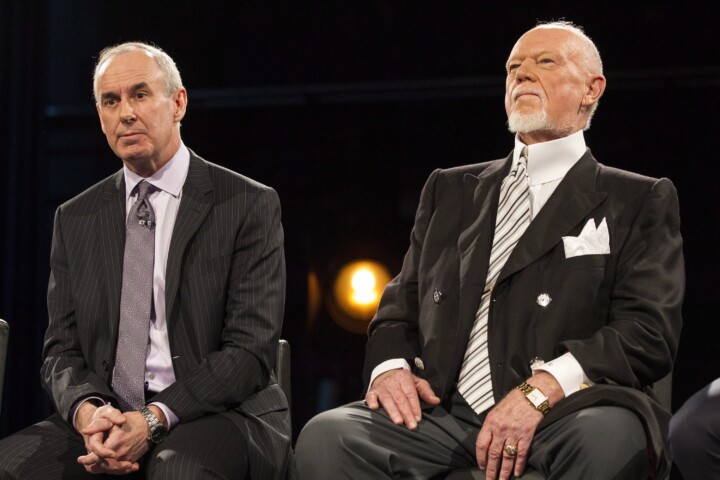

‘Disloyalty to a friend’: Sean Speer on the cultural tension captured by the recent clash between Don Cherry and Ron MacLean

Sean Speer: Maybe Ron MacLean is the one who needs to go

Evan Menzies: Calgary at 150: Why is it so hard to celebrate our history?

Howard Anglin: Canada is badly failing the ‘Tebbit Test’