Last week the popular American economics blogger Noah Smith published an essay entitled “Maximum Canada” in which he outlined the success of Canadian immigration policy and the benefits of a bigger national population.

His observations follow similar commentary in recent months in favour of the so-called “Century Initiative” in which Canada aspires to reach 100 million residents by 2100. The basic premise is that a much larger population would boost Canada’s economic and geopolitical influence around the world, lessen its asymmetry vis-à-vis the United States, and create a bigger domestic market for trade and commerce.

These arguments are generally compelling. There’s certainly something of a correlation between population size and global influence. The exceptions are far outweighed by the rule.

The main problem with this analysis however is that it’s too focused on population growth as an end and fails to properly scrutinize the means. Globe and Mail columnist Andrew Coyne recently argued for instance that the target of 100 million Canadians by 2100 isn’t even that ambitious because it broadly tracks population growth patterns over the past several decades. As he explained:

To get to 100 million in 77 years—two and a half times our current level—implies an annual growth rate of 1.2 per cent. By comparison, over the last 77 years, our population more than tripled, from 12.3 million in 1946. That works out to 1.5 per cent annually. To be sure, birth rates were higher in the 1950s and 1960s; population growth today comes almost exclusively from immigration. Fine: let’s take 1970 as our starting point. Average annual population growth: 1.2 per cent. The Century Initiative proposal is essentially a continuation of the status quo.

Yet there’s something qualitatively different about population growth that’s driven by a combination of natural growth (births minus deaths) and immigration and growth that solely comes from immigration. Smith, Coyne, and others fail to grapple with these key differences.

It doesn’t mean that Canada shouldn’t aspire to have a larger population or even necessarily that we shouldn’t pursue an immigration policy that ultimately gets us there. But before fully signing onto “maximum Canada”, we need to account for the fact that all forms of population growth aren’t the same. (This isn’t, by the way, a normative judgement. It’s merely an observation about the practical differences between a society that draws on immigration to supplement its own natural growth and one that relies on it entirely.)

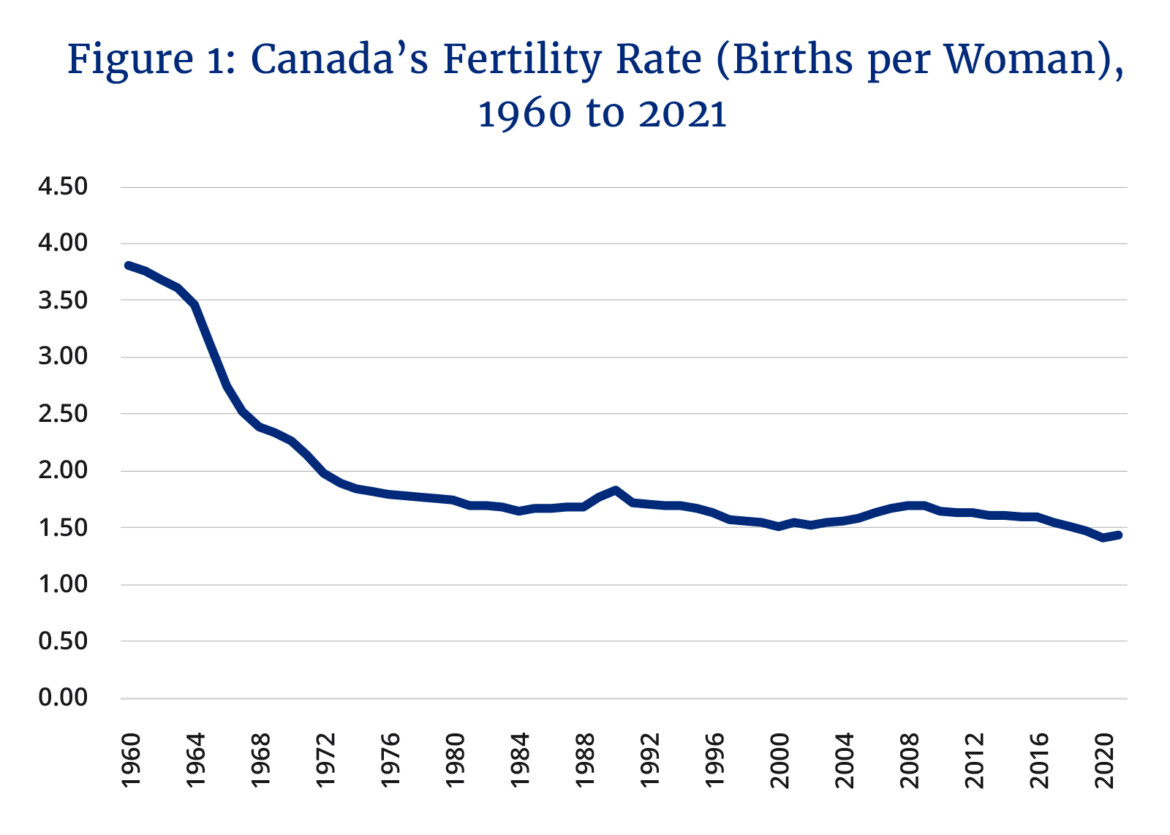

Let’s start with the data. Replacement level fertility is an average of 2.1 children per woman. As Coyne notes, Canada’s fertility rate dipped below replacement level beginning in the early 1970s. It’s now just 1.4 children per woman (see Figure 1).

Although the country’s fertility rate has been below the replacement rate for the past half century, its current rate represents an unprecedented low. As Figure 1 shows, it has steadily fallen to now below the G-7 average and is increasingly one of the lowest rates in the world.

That means that immigration isn’t just doing most of the heavy lifting when it comes to population growth. It’s now nearly solely responsible. Take 2022 for instance. Canada’s population grew by more than 1 million people—the largest single-year growth since 1957—and immigration was responsible for roughly 96 percent.

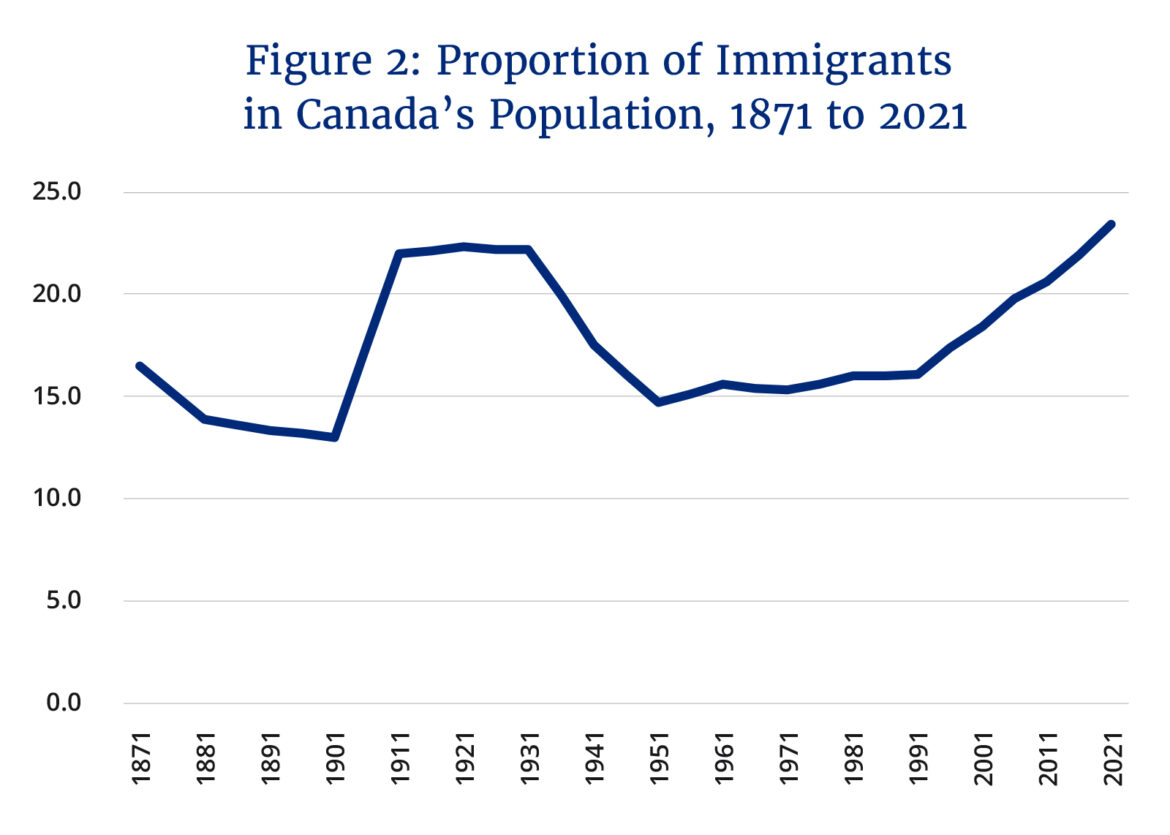

Estimates are that immigration will reach 100 percent of population growth by 2032 and will remain the main driver for the coming decades. As a result, Statistics Canada projects that the overall share of Canada’s immigrant population (which consists of landed immigrants) will rise from 23.4 percent in 2021 (see Figure 2) to as high as 34 percent in 2041.

There are various ways in which immigration-driven population growth is different than natural growth. These differences will ostensibly produce outcomes that are distinct from past experiences and therefore may limit the utility of historical instruction. There’s an onus on proponents of the Century Initiative to account for them in their analysis and advocacy.

The first is that it’s older. Although the immigrant population is generally younger than the average age of non-immigrant residents, it’s still self-evidently older than babies. The majority of immigrants fall within the core working age group (25 to 54). Just over one quarter are aged 15 and younger. Immigration-driven population growth may slow the rise of (and even temporarily lower) the country’s average age but it won’t, according to leading economist David Green, “substantially alter Canada’s age structure and impending increase in the dependency ratio.”

The second is that it’s far less geographically distributed. More than half of recent immigrants settle in Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver and nine of ten settle in a census metropolitan area. Natural growth by contrast would presumably more closely reflect the general distribution of population across the country. Immigration-driven population growth should therefore be expected to impose even greater pressure on housing and other infrastructure in our major cities and contribute to a growing urban-rural divide in our economic and political outcomes.

The third is that it will reshape the country’s culture. That may not be a bad development—particularly in the eyes of those who value diversity—but it still represents a qualitative difference relative to natural growth that requires a bit more attention.

Consider two scenarios. First, there’s a strong possibility that it erodes the place of the French language and francophone culture in our national life as Quebec’s share of the total population declines and its conception of binationalism is fully consumed by multiculturalism. Second, it’s also possible that it could at times conflict with the goal of Indigenous reconciliation to the extent that immigration-driven growth produces a growing share of the population that can plausibly argue that it has no role or responsibility for the historic injustices faced by Indigenous peoples. (There are growing calls—including from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission—to expand newcomer education about the Indigenous experience presumably to mitigate this risk.)

These considerations don’t challenge the case that immigration has been a net positive for the country or that we should maintain high immigration levels in the face of aging demographics or even that we should aspire to a bigger population. They do however dispute the idea that the source of population growth is irrelevant. Natural growth and immigration-driven growth may produce the same number but their effects are necessarily different.

What is envisioned by the Century Initiative and others is essentially without precedent. Immigration has never been solely responsible for such a run-up of Canada’s population. History cannot provide much of a guide. Only prudence can.

A prudent position would be to recognize the benefits of large-scale immigration without assuming that it can be raised to unprecedented levels or become solely responsible for the country’s population growth free from consequence. Maximalist ends without due consideration of the consequences of maximalist means is rarely the basis of good public policy. Immigration is no exception.

Recommended for You

Need to Know: Mark Carney’s digital services tax disaster

Theo Argitis: Carney is dismantling Trudeau’s tax legacy. How will he pay for his plan?

Kirk LaPointe: B.C.’s ferry fiasco is a perfectly Canadian controversy

‘I want to make Canada a freer country’: Conservative MP Andrew Lawton talks being a newbie in Parliament, patriotism, and Pierre Poilievre’s strategy