Canadians have short memories when it comes to politics, often deliberately so. But here’s a fact about Canada’s 2006 election which, for those who forget, ended with Stephen Harper winning his first minority government: it was decided on election night.

Once it became clear the Liberals under incumbent prime minister Paul Martin were solidly trailing Harper’s Conservatives in the seat count, Martin conceded. About two and a half hours after polls closed, the PM informed a crowd in his home riding that he had “just telephoned Stephen Harper and I’ve offered him my congratulations. The people of Canada have chosen him to lead a minority government. I wish him the best.”

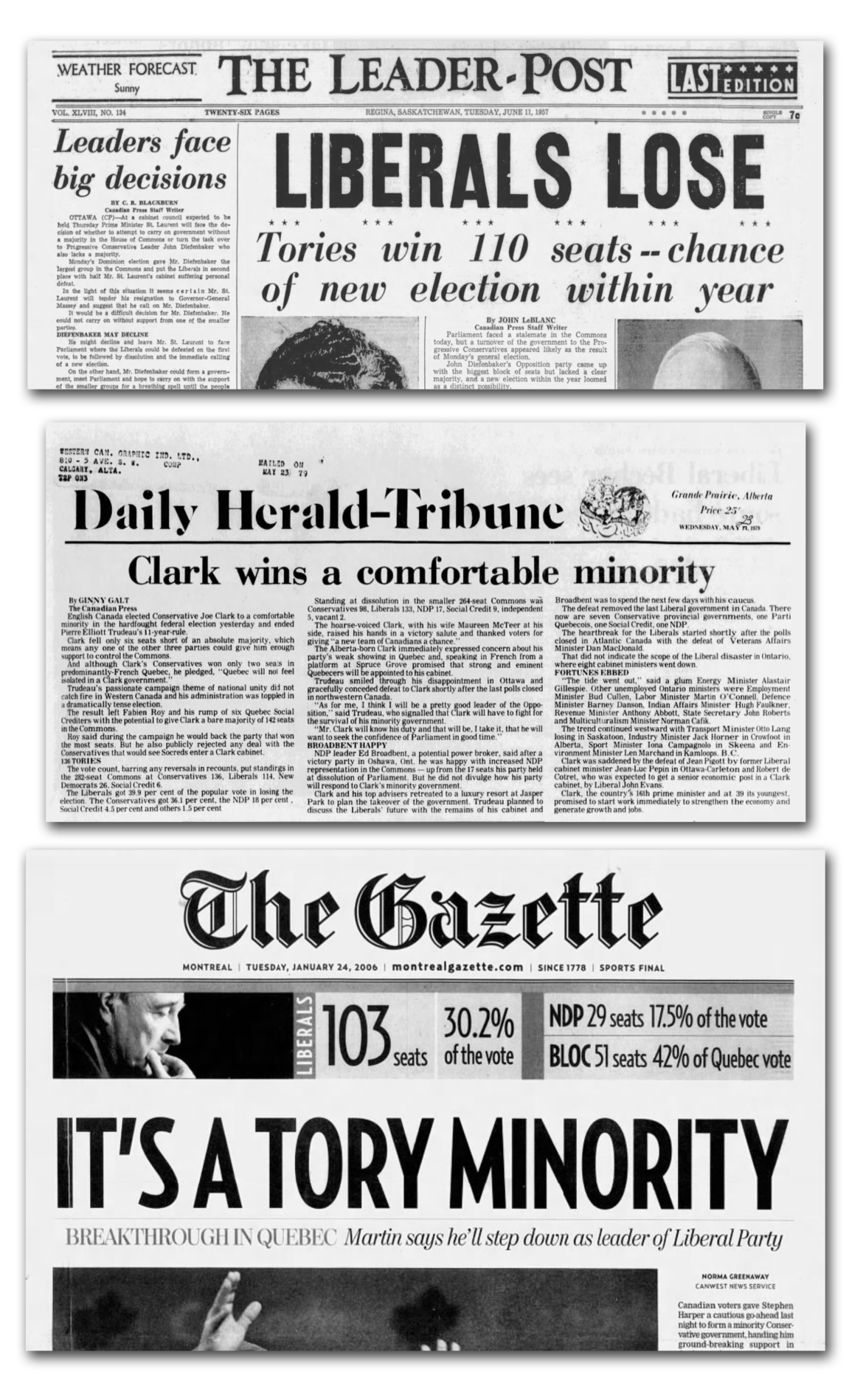

This was after all the big networks had called a Conservative minority; a conclusion that would be similarly blared on front pages across the country the following morning.

Nothing about this was considered controversial. There were no editorials demanding Martin attempt to cling to power, no fiery denunciations of those suggesting Harper had a right to rule.

Harper was sworn in as prime minister a few weeks later and quietly affirmed by a unanimous motion of confidence in the House of Commons a few months after that, an event treated as such an unimportant bit of parliamentary housekeeping it received only the most perfunctory coverage.

Canada’s political culture has clearly changed since then. The question of whether a Conservative minority government can be legitimately elected, and expect to assume power in a smooth and orderly transition, is now treated by many Canadian pundits as a deeply dubious and controversial proposition deserving lengthy debunking and deconstruction. Center-left media outlets now routinely feel the need to grandly declare that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau would actually possess every right in the world to not concede to Pierre Poilievre on election day, even if the Conservative Party wins the most seats in precisely the same fashion Harper did in 2006.

These constant, condescending demands to accept what would clearly be an extraordinarily unusual political situation as entirely unremarkable, combined with ferocious animosity towards anyone who speculates on the potentially severe social consequences of trying to normalize this abnormality, as Sean Speer did on Twitter the other day, gives the whole exercise an air of propaganda and gaslighting. A project, as Speer put it, of Liberals mobilizing “left-wing academics, the broader opinion elite and the (publicly funded) media” in order to legitimize Trudeau refusing to concede power to a Conservative minority government and thereby prolong progressive rule beyond its natural shelf life.

A particularly revealing example popped up on Éric Grenier’s blog the other day; forced to acknowledge that the Canadian news media has a long tradition of declaring minority governments elected on election night, Grenier could only lamely ask that they stop doing this, in order to provide Trudeau some gloss of legitimacy should he attempt to hang on.

It’s strange that even Canada’s most righteously patriotic commentators are loath to suggest Canada possesses any political traditions of its own. The demand is to always take cues from England or Australia on the pretext that Canada is an obedient follower of some transnational system of “Westminster democracy,” but lacks the agency to define the rules of that system for itself.

Canada is a sovereign state, however, and “Westminster system” has never been a precise concept. Indeed, a 2018 Senate report concluded that “Westminster principles” were so inherently slippery, their “most important feature” was simply an “ability to evolve, or adapt, to the historical, regional, and political realities in which they are situated.”

In a Canadian context, this has entailed evolving and adapting unique norms regarding the idea of a “minority government.” As a term, “minority government” wasn’t even a common bit of Canadian political jargon until after the Second World War (when heard earlier, it would just as often refer to a government elected without a majority of the popular vote). As Michael Smith noted in an important 2008 paper, well into the 20th century an outcome where no one party controlled a majority of seats in the House was considered an intimidatingly odd and ambiguous situation because it was so rare. The notorious drama following the 1925 election, which culminated in the so-called King-Byng affair wherein Prime Minister Mackenzie King was fired by Canada’s British governor and a Conservative minority government briefly installed, was far more chaotic and improvised than today’s dry academic retellings make it sound, occurring, as it did, in an age so politically immature even a question like “how many Liberal MPs are there” lacked a precise answer.

It’s a testament to Canada‘s development into a serious democracy that clearer norms have since solidified to make once-ambiguous situations easier to settle. Governor generals are no longer English grandees with an inflated sense of relevance, the business of nominating, identifying, and electing partisan candidates is standardized and easily understood, and yes, a protocol of deciding who runs the country in cases where no party wins a majority (the head of the plurality party) has been established.

Headlines the day after the 1957, 1979, and 2006 elections which saw Conservative minority governments elected.

Admittedly, it would have been better if the norms of how minority governments (or prime ministers in general) are elected in Canada had been codified at some point during the late 20th century (as was once proposed during the constitutional reforms of the 1980s). The fact that they were not leaves us vulnerable to the situation we find ourselves in now. Unwritten norms within a political system, after all, are always subject to a certain cynical calculus, that they’ll only be respected so long as some critical faction of the political elite believes the taboo of breaking them is less severe than the consequences that come with obeying them.

Stephen Harper was widely loathed when he was opposition leader, but the progressive faction of the Canadian political establishment did not regard his 2006 election as an existential threat worth revisiting the settled postwar precedents of Canadian democracy over. The non-event that was his first confidence vote was the sort of chummy “Ottawa consensus” moment that signalled business-as-usual.

That consensus collapsed following the Conservatives’ reelection to a second, larger minority in 2008; an event which radicalized the leadership of the Liberals, NDP and Bloc Quebecois into believing Harper had become such a danger they were justified in requesting the governor-general dismiss him and install Stephane Dion in his place, a public plea for a blunt exertion of royal power unprecedented in Canadian history.

That whole episode can be seen as the moment that damaged Canadian parliamentary democracy beyond repair. It definitively moved Canada out of its postwar consensus, in which minority governments of either party could be uncontroversially elected and unelected via predictable methods, and towards a new status quo in which anyone broadly allied with the political left, the “opinion elite“ as Speer put it, has adopted the position that it is necessary and proper for progressive parties to use any means necessary to prevent the Conservatives from assuming office. The Conservatives are no longer to be regarded as an ordinary party entitled to the same polite conventions of election night concessions and swift transfers of power that have defined the aftermath of previous general elections, but rather an inherently sinister force that can only be permitted to come to power after the parties of the left have exhausted all opportunities to form an anti-Conservative coalition government amongst themselves.

In the face of this new normal, there are several things Conservatives can do to overcome what is, in effect, a broad plot to encourage and normalize a permanent electoral handicap for their party.

The first is to simply ensure Pierre Poilievre will be elected with a majority government. An unambiguous majority victory is what doused the progressive creativity unleashed by the 2008 coalition scheme and it would douse the energies we are seeing now, at least temporarily.

Second, they can continue to observe, loudly and often, what is obviously going on: Anti-Conservative politicians, journalists, and intellectuals encouraging Justin Trudeau to break nearly 100 years of precedent and refuse to concede to a Conservative leader that beats him in the seat count, something former Liberal prime ministers Louis St. Laurent, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, and Paul Martin did with speed and grace.

Third, they can resist the temptation to constantly concede ownership of the rules of the Canadian political system to hostile actors.

Any honest look at Canadian history suggests our parliamentary procedures have evolved slowly and domestically, with any alleged “rules” of the system always more descriptive than prescriptive. Self-styled constitutional experts are not lawyers, they are rarely more than political commentators, in fact, and their theories of what is constitutionally binding have not been tested in court.

The unwritten rules of Canadian democracy have always rested as much on public standards of what’s fair and familiar as anything else, and Conservatives should not be shy about appealing to these common sense instincts of justice above the angry essays of those who hate them.

Recommended for You

The Notebook by Theo Argitis: Carney’s One Big Beautiful Tax Cut, and fresh budget lessons from the U.K.

‘A fiscal headache for Mark Carney’: The Roundtable on how Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill could affect Canada

Ginny Roth: How vacant liberal nationalism left Canada worse off than George Grant even imagined

Peter Menzies: Justin Trudeau’s legislative legacy is still haunting the Liberals