Canadians appear to be a particularly miserable lot these days if one is to take media reports at face value. The recent bout of inflation and interest rate increases appear to have brought about a particular phase of economic hardship that has spilled over into personal lives, and that hardship appears to be across the board in terms of demographic and income groups. As a result of financial struggles, inflation, and high interest rates are affecting Canadians’ mental health, according to one report fueling anxiety over housing and food.

Millennials—particularly those who own a home—are apparently poised to face the most economic pain as interest rate costs steepen on strained debt loads and economic damage lays waste to the economy and expectations. Burdened by debt and rising housing costs, three-in-ten Canadians are “struggling” to get by, with the number of mortgage holders voicing difficulty meeting housing costs up 11 percent compared to last June. If you have someplace to live, you are hard-pressed to pay the bills, and if you do not have a place to live, then you are miserable because you cannot find one.

With so much misery, it is surprising that the misery index has not been resurrected by assorted pundits as a measure of how miserable we all are. The misery index is an economic indicator first created by economist Arthur Okun during the 1970s which was an era of high inflation and high unemployment known as stagflation in the wake of the oil price shock and its macroeconomic impact. The misery index was constructed by adding up the rate of inflation with the unemployment rate with higher totals being associated with greater economic misery experienced on the part of the public. The index has also on occasion been expanded by including variables such as the bank lending rate. While not a perfect measure of economic welfare, it might nevertheless be useful to see if the current mood of economic angst and misery is captured by such an index.

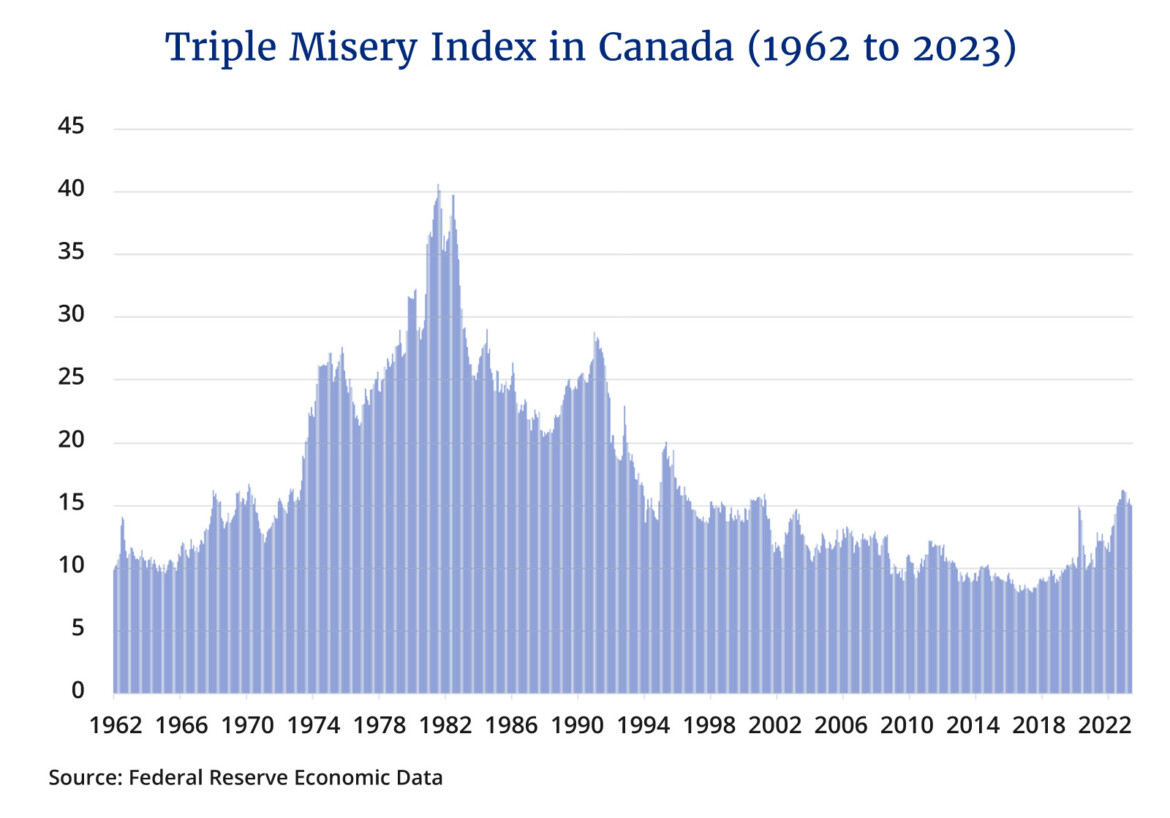

Using data obtained from the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) source of the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, the accompanying figure plots a monthly triple misery index consisting of the sum of Canada’s CPI inflation rate, its monthly unemployment rate, and the central bank rate for the period 1962 to 2023. Such a lengthy time span allows us to examine Canadian misery over time and it is quite an eye-opener. The 1960s were truly a golden age for the economy and were accompanied by some of the lowest values of misery in sixty years. Misery began to rise during the 1970s and appears to have peaked in the early 1980s, during which there was an unemployment rate that peaked at 13 percent, inflation that peaked at over 12 percent, and a bank rate that believe it or not hit over 20 percent one month making the current 5 percent seem like a monetary tea party.

After its early 1980s peak, misery declined with a major rebound in the early 1990s and then declined again, steadily bottoming out at values slightly lower than even the 1960s during 2017. Since 2017, they have risen, and based on the chart we are now at a point where we are at least as miserable as we were in the 1990s. Over the entire 1962 to 2023 period, this triple misery index has averaged a value of 16.8. As of June 2023, the Canadian misery value is 15—just a bit below the historical average.

The most miserable month in Canada was August of 1981 when the value of the misery index hit 40.6. During that month, the unemployment rate was 7.2 percent, the bank rate was 20.9 percent, and inflation clocked in at 12.5 percent. The least miserable month in Canada was June of 2017 which came in at a value of 8. The unemployment rate was 6.2 percent, the bank rate was 1 percent, and the inflation rate was just over 1 percent.

The misery index charted here does show that misery has been growing since 2017 but it is currently below the historical average—and indeed it is still lower than the early to mid 1990s. It is definitely much lower than the period stretching from the mid-1970s to nearly 1990. And yet, if one talks to people and follows social or mainstream media, one seems to get the impression that things are much worse than the misery index would suggest. So, the question really is, why are Canadians feeling so miserable given that by historical standards, the misery index is nowhere near past historical peaks?

This is indeed a perplexing and important question. One possibility is that the indicator is not fully capturing the misery of Canada today because there is more to misery than just the sum of the unemployment, interest, and inflation rates. Perhaps we should be including other economic variables, such as the growth rate of real per capita GDP, or perhaps a separate inflationary index for components such as rents and housing. This would suggest that the structure of misery is not as simple as it once was but, like the country as a whole, has become more complex and diverse and the misery index needs a major revamping.

Another possibility is the old adage that in life and politics, timing is everything. While the recent surge in misery is modest by some previous historical episodes, it comes after a nearly 20-year period of low and declining misery. It also comes right after a global pandemic and several years of anxiety, change, and disruption that has left everyone more short-tempered and less tolerant than usual.

It remains that the last twenty years have been marked by an era of low inflation, low interest rates and low unemployment, and numerous cohorts have come onto the labour market knowing only cheap money and never seeing recessions like that of 1981-82 or 1991. There may even be an issue of economic literacy at play here given that many are expecting relief from lower inflation rates and do not realize that a lower inflation rate means a slower growth in prices and not a return to price levels from a decade ago.

Or perhaps Canadians themselves have changed and have become less resilient in the face of adversity of any kind. After all, given the rhetoric, many came to feel that the pandemic was akin to a war and siege conditions. While the pandemic in Canada was indeed serious, it affected portions of the population differently. While some were on the front lines bearing the brunt of the pandemic—for example, health workers—others were not. Most wars involve widespread death and destruction of human life and physical and social infrastructure. They are generally not characterized by a situation where many can work from home, the government sends you enhanced transfer payments like the CERB, and you can order takeaway and watch Netflix.

Whatever the reason, the reality is Canadians feel more anxious, miserable, and petulant than usual, and this will inevitably spill over into the political arena.

Recommended for You

Carney gets a majority, but Canadians vote the Liberals out in a snap election: The Hub predicts 2026

A rocky road for Ontario, and an unconventional CUSMA renegotiation: The Hub predicts 2026

Poilievre will survive as CPC leader, and Canada will stay golden in men’s hockey: The Hub predicts 2026

Supply management will be sacrificed to appease Trump, and the Netflix takeover is bad for Hollywood: The Hub predicts 2026