Families across Canada are struggling with high food prices.

On average, food costs 18 percent more in July this year compared to two years earlier. This is much faster than the usual 2 percent annual price growth. Indeed, it’s the most rapid acceleration in food price growth since the late 1970s. And for an average family, this adds roughly $150 per month in additional costs.

No wonder the government is under so much pressure to act.

Last week, the government finally announced a plan. If you can call it that.

As part of a broader package that primarily aimed to boost housing construction, the government also announced what it described as “concrete actions to stabilize food prices.”

First, it will browbeat corporations by calling leaders of large grocery chains to “an immediate meeting in Ottawa.” Second, they will consider taxing grocery stores.

At first glance, this makes no sense.

With a little more thought, it makes even less.

Taxing grocers will not ”restore the grocery price stability that Canadians expect,” as they claim. Neither will stern words.

But conveniently for the government, that may not matter. There are strong indications that food prices may stabilize soon regardless, allowing the government to claim victory.

Let us first examine the government’s main, if only implicit, claim: corporate greed and a lack of competition cause high food prices.

Many agree. Corporations are an easy political target, after all. And the government’s NDP partners, for example, focus almost exclusively on this as the primary cause of inflation.

I wrote at length on this for The Hub last year. The data is crystal clear: rising profit margins are not a particularly important cause of rising prices. Those conclusions remain as true today as they were then, and they are as true for food as they are for inflation overall.

Food and beverage retailers in Canada earned roughly 4.2 cents in profit per dollar sold in the second quarter of this year. Although up from 3.7 cents a year earlier, this is not a major factor in rising food prices. For perspective, this contributed 0.5 percentage points to the 9.1 percent food price increase between the second quarters of 2022 and 2023. That’s not zero. But it’s close.

Even over a longer period, changing markups account for little. Since early 2020, grocery prices have risen by 21 percent. Had markups not increased, they’d be up by 20 percent.

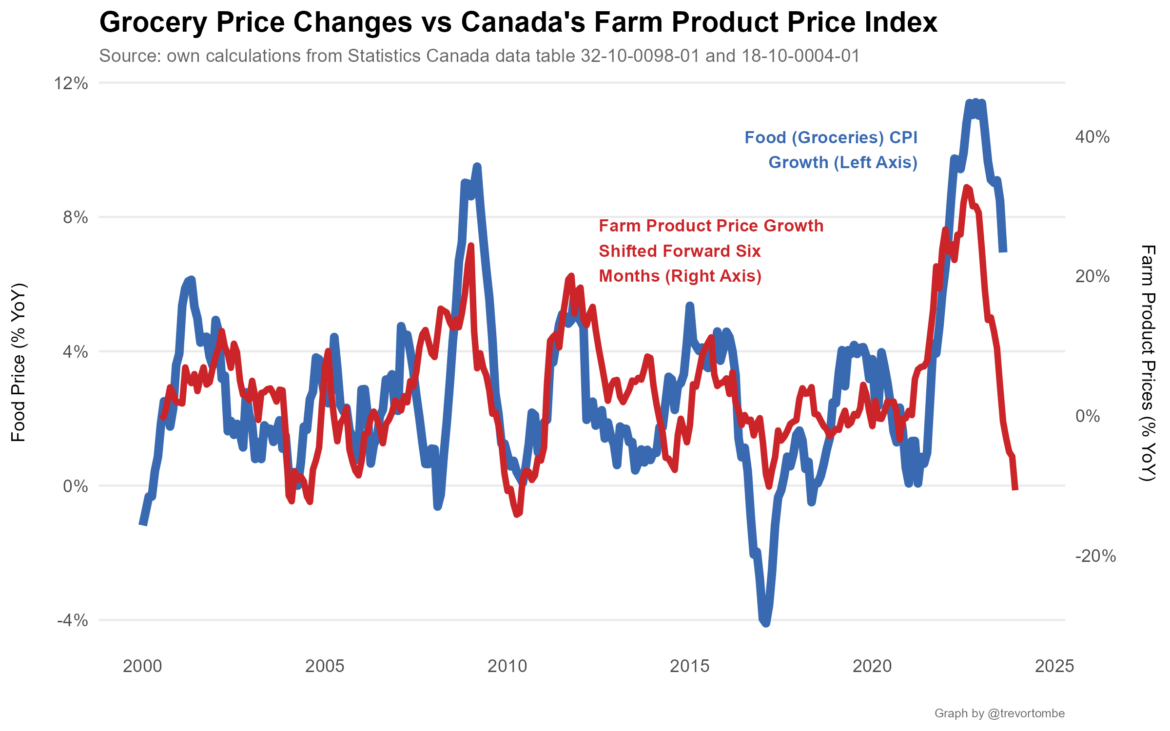

A key driver of grocery price changes is not corporate greed but farm product prices and input costs, including for producers elsewhere in the world.

There’s good news for consumers here: the cost of many important farm inputs has fallen recently. Machinery fuel is down nearly 27 percent since its peak last year, and fertilizer is down nearly 17 percent. This is already showing up in the price of many important farm products. The price of grains is down 8 percent so far this year, for example.

Not everything is down, to be clear. Cattle and livestock prices are way up. But overall, farm products are nearly 11 percent cheaper compared to a year earlier. This may soon benefit consumers.

Historically, grocery price movements lag farm products by roughly six months. If this pattern continues—as it should—then we’ll soon see a sharp drop in grocery price growth. By December, average grocery prices could possibly even be lower than they were a year ago.

The government will naturally claim credit. It was their harsh words and threat of a tax, they’ll almost surely say, that caused prices to stabilize.

It’s hard to see this as anything but a cynical move to mislead Canadians, cast blame on a politically unpopular group, and claim credit for improvements that were beyond their control.

That is bad enough. What was worse about the government’s plan was what it did not contain.

If politicians wanted to lower food prices, they would repeal policies that deliberately raise them.

Canada has several artificial and restrictive agricultural policies. We force farmers to hold costly licenses to produce milk, for example, and impose prohibitive tariffs of almost 300 percent on imports. Want a dairy cow in Alberta? The permit alone will run you roughly $50,000. The effect on prices of this policy—known as “supply management”—should be obvious.

Actual estimates are stark. Eliminating supply management for milk would cut prices nearly in half, according to the OECD. This adds up. One in every seven dollars spent on groceries by the typical Canadian family is spent on dairy products. If the policy of artificially raising these prices were repealed, we’d each save roughly $40 per month. Milk alone cost consumers $3.9 billion more in 2021, according to the OECD. Add $600 million for poultry and $300 million for eggs, and consumers pay nearly $5 billion more in total for groceries.

Support for policies that raise food prices is, to be clear, an all-party problem. Conservatives, Liberals, and the NDP dare not touch it. Dairy farmers have a powerful lobby.

Scrapping this system would also come with costs, as we’d compensate farmers for the losses they suffer. But it would be better for those short-term transition costs to be borne by government than permanently by families simply buying milk.

Until then, we’re stuck with a federal plan that falls apart under the slightest scrutiny. But politically—it pains me to say—that may not matter.

Recommended for You

‘Our role is to ask uncomfortable questions’: The Full Press on why transgender issues are the third rail of Canadian journalism

Need to Know: Mark Carney’s digital services tax disaster

Sean Speer: Investing in critical minerals isn’t just good business, it’s a national security imperative

Theo Argitis: Carney is dismantling Trudeau’s tax legacy. How will he pay for his plan?