In September, Statistics Canada released the results of their 2022 Mental Health and Access to Care Survey, and it shows that far more Canadians are depressed and anxious today than they were a decade ago.

The survey, which is conducted every ten years, involves thousands of Canadians reporting their mental health symptoms in depth. Statistics Canada then uses those symptoms to determine whether individuals meet the diagnostic criteria for mental disorders.

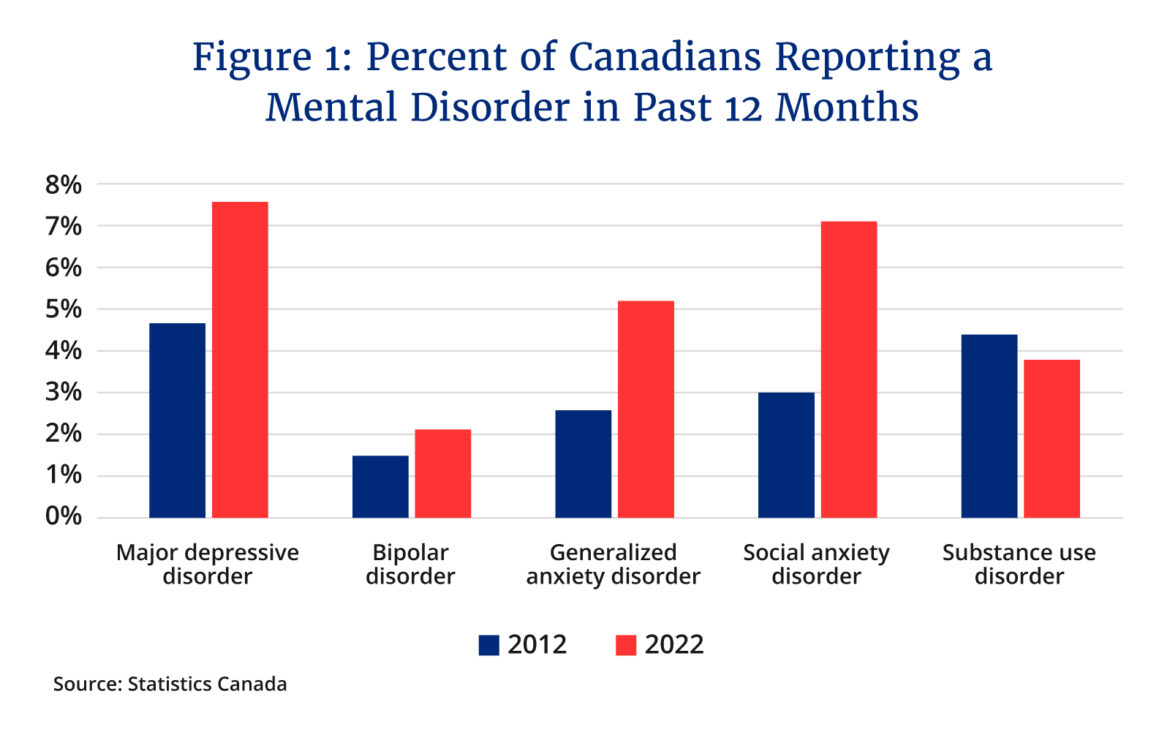

Since 2012, the number of Canadians with major depressive disorder has increased by 62 percent. Today one in 13 Canadians, 7.6 percent of the population, qualify for the diagnosis. The number of Canadians with anxiety disorders has doubled, with one in 14 (7.1 percent) now suffering from social anxiety disorder. Rates of bipolar disorder rose and substance use disorder fell by 0.6 percent each, with the fall in substance abuse driven by declining alcoholism.

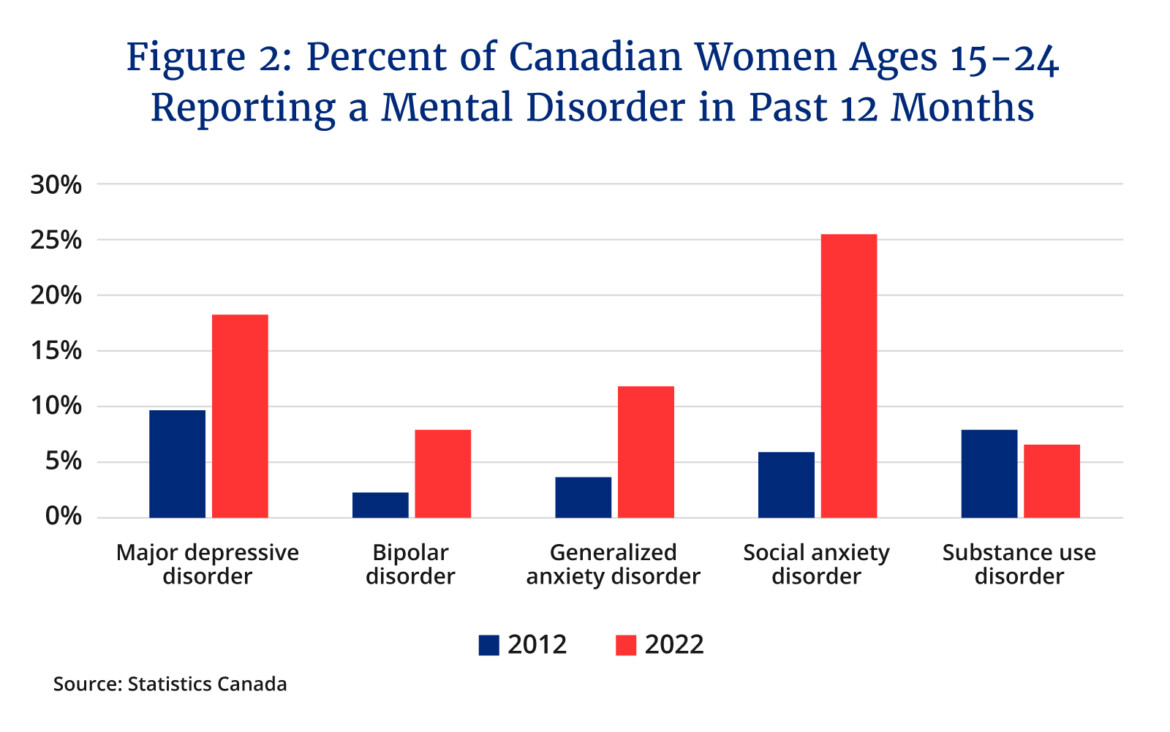

While mental illness is much higher among the general population today than it was a decade ago, the rates among young Canadians, particularly young women, are staggering. One in four Canadian women between the ages of 15 and 24 qualify for social anxiety disorder, and nearly one in five qualify for major depressive disorder. This is a big increase from a decade ago when those numbers were about half of what they are now.

Young Canadian men are half as likely to have a mood disorder as young women but are more likely to be addicted to alcohol, cannabis, or drugs, with one in 10 qualifying for a substance use disorder. They are also three times as likely to die by suicide though young women are far more likely to attempt.

The surge in mental health issues among Canadians in the past decade is the result of several factors. Canada’s stagnant economy and the rising cost of living play a significant role. In a recent poll from Mental Health Research Canada, 39 percent of Canadians said that economic issues were impacting their mental health with debt, inflation, rent or mortgage payments, and food costs driving up anxiety and depression. Worse still, the poll showed that 41 percent of Canadians facing financial challenges had thought about killing themselves in the past year.

Young Canadians today are the first generation to grow up with social media as an integral part of their lives, and its effects on their mental health are becoming apparent. Social media has changed how we interact with one another and led to more social comparison and cyberbullying. Statistics Canada’s Online Harms Report found that a quarter of Canadian teenagers and young adults report being bullied or harassed online. This percentage rises to 35 percent among those who are constantly online or have trouble making friends.

Research compiled by social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has shown that the rise of widespread social media and smartphone usage starting around 2012 has negatively impacted the mental health of young women in Canada and across the world, which explains some of the gender differences we see in recent data.

Of course, the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftereffects deserve a good share of the blame. Lockdowns, isolation, fear of sickness, and growing political polarization have all taken a toll on the Canadian psyche in recent years. Statistics Canada’s Mental Illness During the Pandemic Survey found that Canadians whose incomes fell during the pandemic were one and a half times more likely to be depressed or anxious than those whose incomes rose. Front-line workers were also one and a half times as likely to be depressed or anxious as those not on the front line. However, it would be a mistake to attribute too much of the general increase in mental disorders to COVID as rates of mental illness were rising before 2020.

To tackle the rise in mental health issues, the federal government has funded an online portal of mental health and addiction resources, announced a 988 mental health crisis hotline, and earmarked $12 million to develop ten “wellness hubs” which are part of a Canada-wide effort to make mental health care more community-based and accessible. Mental health organizations, however, believe these investments to be insufficient, and want the Liberals to keep their 2021 campaign promise of a $4.5 billion mental health transfer to the provinces.

As demand for mental health services has surged, wait times to see a mental health care professional have risen. A 2022 poll by the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) found that one in four Ontarians had sought help for mental health challenges in the past year and that 43 percent found it difficult to access mental health supports. Despite long wait times to see publicly covered mental health specialists, a 2023 poll from CMHA found that 87 percent of Canadians want universal mental health care, as many say they cannot afford to pay out of pocket. Under the Canada Health Act of 1984, only mental health services provided by a physician or in a hospital are publicly funded.

As these alarming statistics show, Canada is in the midst of a mental health crisis. Economic challenges, rising social media use, and the COVID-19 pandemic have culminated in a surge of anxiety and depression which we lack the capability to fully address. With rates of mental illness rising, analysts predicting stagnant incomes for the next four decades, and the ascendance of artificial intelligence and virtual reality technologies that will blur the boundary between real and digital, an effective plan to tackle mental health in all its forms and complexities is needed more than ever.

Recommended for You

Michael Kaumeyer: Polite decline: Canada’s aversion to being our best is holding us back

Howard Anglin: Lament for a Lament

‘A place where anybody, from anywhere, can do anything’: The Hub celebrates Canada Day

Peter Menzies: It’s no wonder Canadians are tuning out the legacy media