Canadians would be forgiven for thinking that grocery stores are where food is made given how much attention they are getting in the debate about food inflation.

While they may be where most consumers interact with the food system, consumers pay at the checkout for what can be a long, complex value chain. Governments must look past the checkout if they want to take more substantive action to tackle food affordability.

Policymakers are not usually lucky enough to get evidence this consistent. The Bank of Canada, academics, researchers, and public institutions in the US and EU all point to food inflation being driven higher by a long list of causes. Most conclude that inflation will slow when those causes, from Russia’s war to higher interest rates, resolve themselves.

While consistent evidence may make for good policy, it doesn’t always make for good politics. Politics seems to be driving the focus on grocery stores and CEOs. Many politicians have jumped on the bandwagon, with the government demanding retailers take “immediate action to stabilize food prices.”

Thursday’s announcement from the government trumpeted the results of those demands. Grocers will offer “aggressive discounts…, price freezes, and price-matching campaigns.” The government will also increase support for its internal consumer advocacy unit, continue to support industry-led efforts to establish a voluntary Grocery Code of Conduct and improve the availability and accessibility of data.

These steps build on the recent Affordable Housing and Groceries Act. The Act should increase transparency, but likely not lead to more affordable groceries.

More affordable groceries require a more substantive approach.

Even the recent Competition Bureau report which concluded that grocery margins in Canada have increased by a “modest, yet meaningful” amount highlighted that the grocery sector is a low-margin, competitive business. The Bureau cites foreign retailers who admit that “it could be difficult to compete on price” in Canada.

The actions promised to the government by the retailers, including price matching and steep discounts on some products reflect the typical competitive business practices in a concentrated but competitive sector.

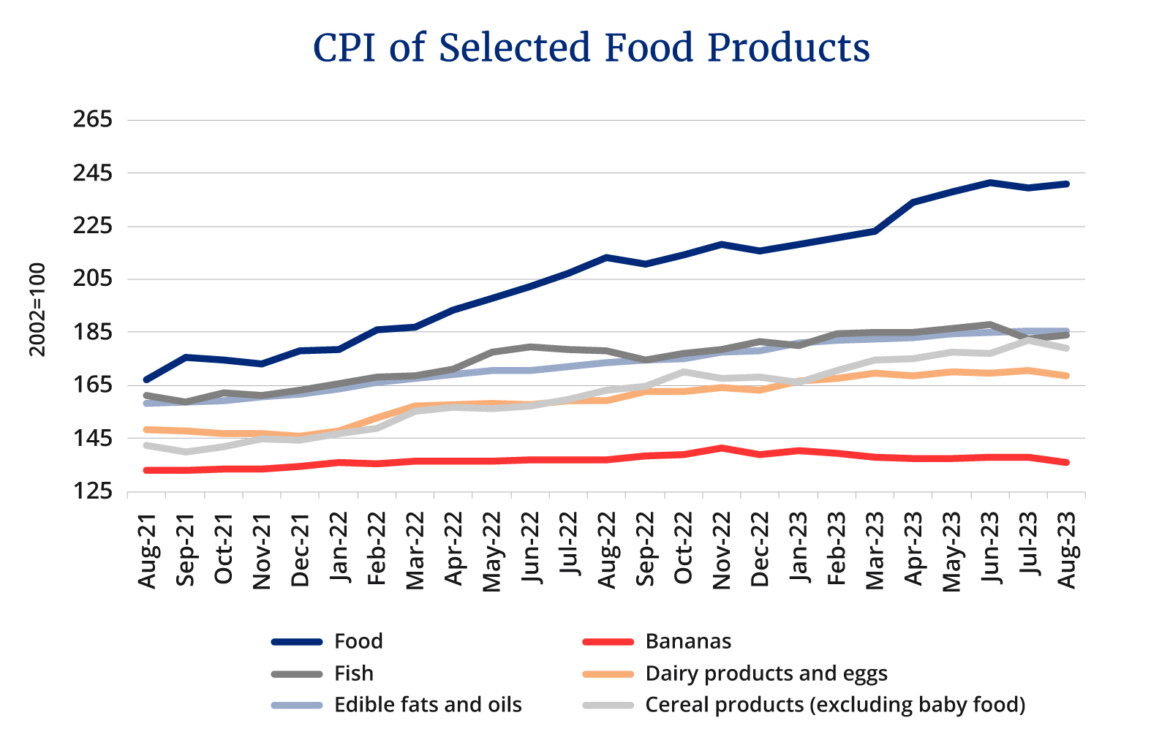

The focus on retail continues to miss that it is a complex, dynamic set of pressures that are keeping food prices high. The variation in inflation inside the grocery store itself underscores how complex the issue is.

These dynamics may not lend themselves to easy solutions, but they do offer governments more levers to pull to offer short-, medium- and long-term relief from food inflation. There is a recent example for how governments should tackle challenges like this.

In the midst of global supply chain disruptions, the government launched a National Supply Chain Task Force with the objective of making independent recommendations regarding “short and long term actions to alleviate supply chain congestion.”

The final report lays out a series of recommendations built around the theme of “Action. Collaboration. Transformation.” The recommendations address factors ranging from service reliability and resilience to shifts in governance.

Launching a food affordability task force is not as flashy as convening grocery CEOs in Ottawa, but it should enable more substantive action. The task force should have three priority mandates.

First, it should build on the commitment to increase the availability of data by producing detailed analysis on food inflation drivers along the value chain. A good example of the analysis the task force should do is the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Dollar research program, which breaks down the cost components of the value-chain.

Second, the task force should make concrete recommendations for the public and private sector. The task force should acknowledge global forces, but focus on where Canadians can act. This could include looking at the dynamics at the retail level, but must also include an examination of systemic issues including supply chain fluidity, regulatory burden and taxes and recommending where costs can be driven down.

Finally, the task force should look at where the government can take immediate, targeted, actions to support those hit hardest by high food prices. This should include considering the recommendations of Food Banks Canada who recently gave Canada a D+ in its inaugural Poverty Report Card. The report highlights that while food prices are the result of the food system, the impact is part of a broader poverty challenge that must involve solutions beyond the food system’s scope.

Unfortunately, the Supply Chain Task Force has shown that writing the action plan can be the easy part, acting on it is harder.

Complex issues do not tend to lend themselves to the silver bullets governments prefer. While the government says “all options are on the table” to “stabilize” prices, there seems to be a focus on CEOs and theoretical windfall profits. Other solutions such as exempting food from the carbon price (as is done with GST) or changing sensitive ag policy don’t appear to be on the table.

The good news is that the evidence already points to slowing food inflation. The day that the prime minister announced the government was summoning the CEOs to Ottawa, the Globe and Mail ran a story about the long slow return to normal of food prices. The day after the grocery CEOs were in Ottawa, Statscan confirmed that the annual growth in food prices had slowed to its slowest rate since February 2022.

Even if inflation slows, many of the pressures will remain. If the political pressure falls with food inflation, the opportunity will still exist to do something substantive. It may not be easy, but it would be worthwhile.

Recommended for You

Crystal Smith and Eva Clayton: Indigenous natural resources development is an efficient, fair, and responsible way to advance economic reconciliation

Matthew Grills: Joey Chestnut is America

Peter Menzies: Justin Trudeau’s legislative legacy is still haunting the Liberals

‘There are consequences to this legislation’: Michael Geist on why the Canada-U.S. digital services tax dustup was a long time coming