The Hub is pleased to present a weekly column from author and historian Antony Anderson on the week that was in Canadian history.

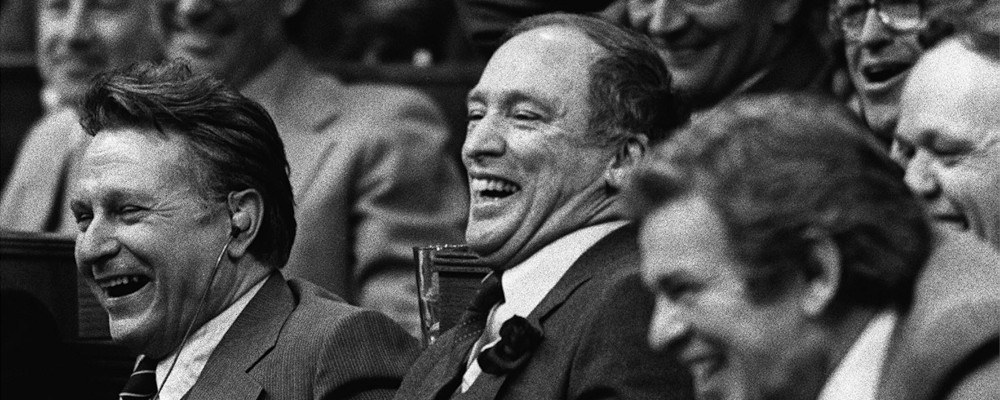

February 18, 1980: Pierre Trudeau wins the election and returns to power

Only four prime ministers have come back from the political grave: Sir John A. Macdonald, William Lyon Mackenzie King, Arthur Meighen (if only for a few months), and Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Their peers either looked at the numbers and retired to avoid evisceration, or lingered, lost and languished in the thankless limbo of loyal opposition before limping away to elder statesmanship.

By the spring of 1979, Trudeau had wielded power for 11 years, full of all the turbulence a healthy democracy generates. His great accomplishment was to embody and bring the French fact, as it was called, into Ottawa and more importantly into the national imagination. After Trudeau, there was no going back to a dysfunctional federation where citizens who spoke one of the country’s official languages were cut off from essential government services and seats of power and a sense of belonging.

To govern is to piss off one’s fellow citizens, and Trudeau had done his fair share of that. He had confronted grumbling provinces (nothing new) and looked, depending on one’s geography, like a strong leader fighting for national dreams or a malevolent centralising central Canadian. As if to mock his efforts and at the same time underline how essential his efforts remained, the separatist Parti Québécois had come to power in Quebec in 1976 and suddenly the entire national experiment seemed to hang in the balance.

On that point, many Canadians were grateful a francophone prime minister was making a credible case for keeping the show on the road. But the philosopher king was also compelled to tackle the more prosaic though equally critical challenges of stagflation, inflation, recessions, oil shocks, and other economic plagues that defied easy remedies in Canada and the rest of the struggling Western economies (no matter how intensely newspaper editorials and economists thundered out their solutions). By 1979, Trudeau was admired and loathed, familiar and yet still singular, brilliant, and disconnected—and then his time ran out. He had to call the election for May 1979.

This was his first campaign against newish opposition leaders: Joe Clark, Progressive Conservative, and Ed Broadbent, NDP. In this generally forgettable contest, there were no knock-out punches or game-changing blunders. Clark was fresh and decent but never compelling enough. Trudeau was a known quantity, for better and for worse. One of the best political observers of the era, Ron Graham wrote, “Canadians had shown themselves willing to put up with a lot of his arrogance and foibles for the sake of his obvious qualities; but if they were to be led by the weak and confused, then at least Joe Clark was nice.”

For all the electorate’s ambivalence and fatigue, the Liberals won the popular vote—40 percent to 36 percent for the Conservatives. However as often happens in the confounding first-past-the-post shuffling the Tories secured the most seats, 136 to the Liberal’s 114. The NDP took 26. Ignoring parliamentary right and following local custom, Trudeau declined to cobble together support from the smaller parties so he could remain in power. Clark, the youngest PM in Canadian history, would prop up his stay in the PMO on the six seats held by a Quebec protest party, the Ralliement des Créditistes. That election night, Trudeau consoled sobbing supporters in a ballroom at the Chateau Laurier with a line from the much-invoked Desiderata, “With all its sham, drudgery and broken dreams, it’s still a beautiful world. Strive to be happy.”

In the months after the election loss, Trudeau did strive to do his duty from an unfamiliar vantage point on the opposition benches, but he also seemed to get bored with the job description, go on canoe trips, grow a beard, shave it off, and, in the wake of his failed marriage, dote on his three young boys. He wandered all over the emotional map and then in November, aged 60, he announced his resignation as Liberal leader. A turbulent, creative season in Canadian politics was surely drawing to a close; again, a joyous relief to some citizens, a deep loss for others.

Trudeau no doubt read his political obituaries which, when not simply negative, shared a note of disappointment that he hadn’t lived up to his potential—though given the mania that surrounded his first years in power, what mere mortal could? While his wise biographer John English judged rightly that those “political obituaries mirrored recent controversies rather than mature reflection,” even Prof. English conceded, “Had Trudeau’s political life ended in 1979, he would probably not have ranked among the ‘great’ Canadian prime ministers.” The middling verdicts must have stung such a fierce competitor. And then there was the looming referendum in Quebec which the separatists had called once they knew their most formidable foe was withdrawing from the battlefield.

Despite the public show of unanimity, not everyone in the Liberal party shed tears in private, especially not in Ontario or the West. There were significant numbers, respectful of his public service, who wanted a change and strong, attractive contenders hovered in the wings with promises of a return to power.

In the meantime, Joe Clark, who had declared that he would govern as if he had a majority, was learning on the job all about the galling gap between promises and solid ground. He had to reverse his pledge to recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. He could no more easily make peace with the endlessly grumbling premiers than his supposedly high-handed predecessor. His notion of Canada as “a community of communities” was perhaps more subtle and true than Trudeau’s championing of “One Canada” but it didn’t have that ring of passion that even modest Canadians crave from time to time. And then on December 13th, to restore financial health, the government introduced a budget packed with the bitter medicine of steep taxes.

The Liberals were down, officially leaderless but nowhere near out—they were doing well in the polls and enough of them sniffed an opening in their opponent’s plan to inflict pain on the smokers, beer drinkers, and gas guzzlers of the land. In that jolly Christmas season, influential caucus members stoked ambitions, rallied courage, and moulded the decision to bring down the government a mere seven months after the election. Our parliamentary system was made for this mix of ruthlessness and principle.

Clark’s team missed warning signs, underestimated their opponents’ resolve, failed to take care of the Creditistes whose six votes were absolutely vital, and did not do their sums properly. Late on the evening of December 13th, to their utter astonishment, the Conservatives lost the all-important vote of confidence.

Having toppled the government, the Liberals had to figure out who would lead them into the next election—no obvious thing for days. Loyal backroom advisors and MPs went to work on doubters and critics in caucus and most critically on Trudeau himself. His boys were central in his calculations, but the referendum was coming in May and he wanted to patriate the amending formula and bring in a charter of rights. The federalist side needed a champion and it was hard to pinpoint anyone in the House of Commons who would care about the Constitution with the same precision and tenacity. He was not one for turning away. So he returned.

In February 1980, defying the odds of history, Trudeau managed his release from loyal opposition and savoured another majority triumph, anchored in Quebec, erased in Western Canada—a schism for another leader to heal. In what he knew all too well was his final round, he achieved his great victories, controversial and inconclusive as these things are in our ongoing work-in-progress. But who else would have defeated the separatists in the referendum, buying precious time; brought in a Charter of Rights that causes us, properly, to constantly weigh and argue over balances of power between elected officials and appointed judges and citizens; and patriate the amending formula completing an odyssey towards independence begun by Sir Robert Borden.

When he stepped down for good in 1984, he would have seen that in his second retirement, he had recast both his country and his political obituaries. Not bad for a world of sham, drudgery, and broken dreams.

Recommended for You

Welcome to the age of great power capitulation: The Hub predicts 2026

A rocky road for Ontario, and an unconventional CUSMA renegotiation: The Hub predicts 2026

Poilievre will survive as CPC leader, and Canada will stay golden in men’s hockey: The Hub predicts 2026

Supply management will be sacrificed to appease Trump, and the Netflix takeover is bad for Hollywood: The Hub predicts 2026