Federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault may have erred last week by saying “the federal government will no longer provide funding to expand the road network.” If he was serious, that would mark a significant federal policy shift and stall future infrastructure projects nationwide.

Reactions were swift. Ontario’s Premier Ford was “gobsmacked”.

The minister’s attempt to clarify—saying federal funding would not support “large projects”—did little to help.

I won’t pile on. The minister often struggles to clearly articulate key federal policy decisions. But whether serious or not, his comments touch on a critical challenge for Canada: our transport infrastructure is inadequate and our productivity suffers as a result.

The task of connecting Canadians is vital for our economic health and well-being. As is the task of connecting us with the world. This isn’t easy in a country with relatively few major cities spread out over vast distances, but it would be impossible without trucks and major roads.

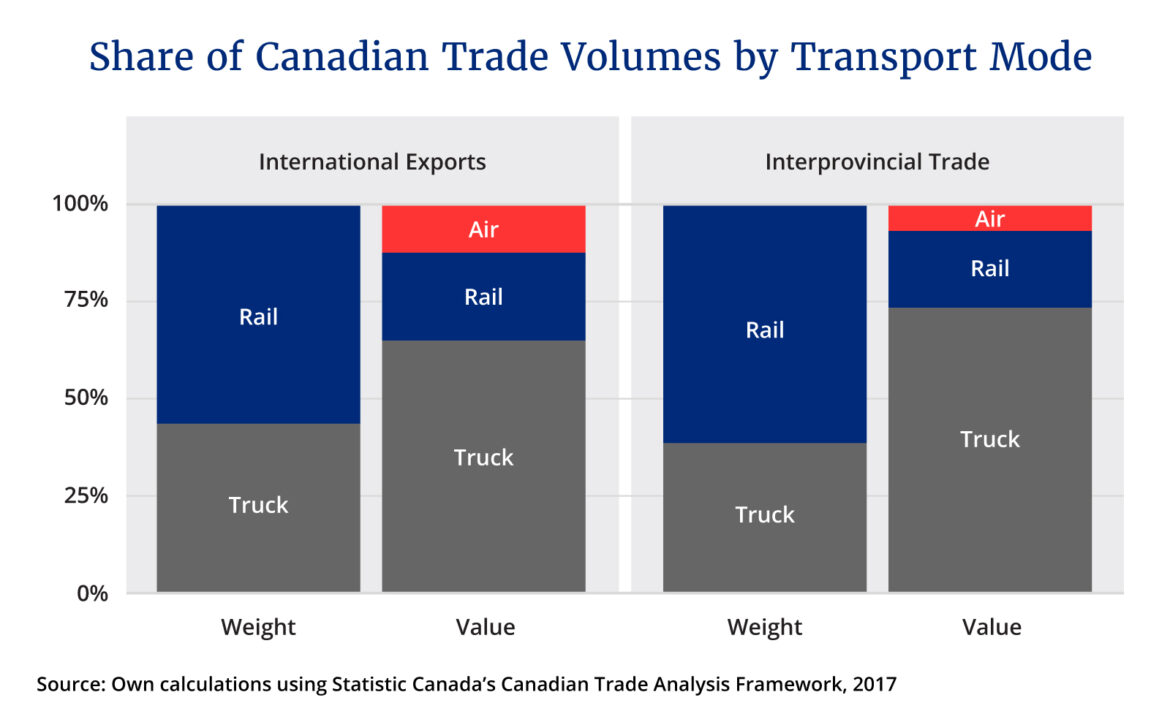

Internally, I estimate roughly three-quarters of everything we trade across provinces is shipped by truck. Internationally, roughly two-thirds of our exports are shipped that way. Rail is important too, of course, mainly for heavy items.

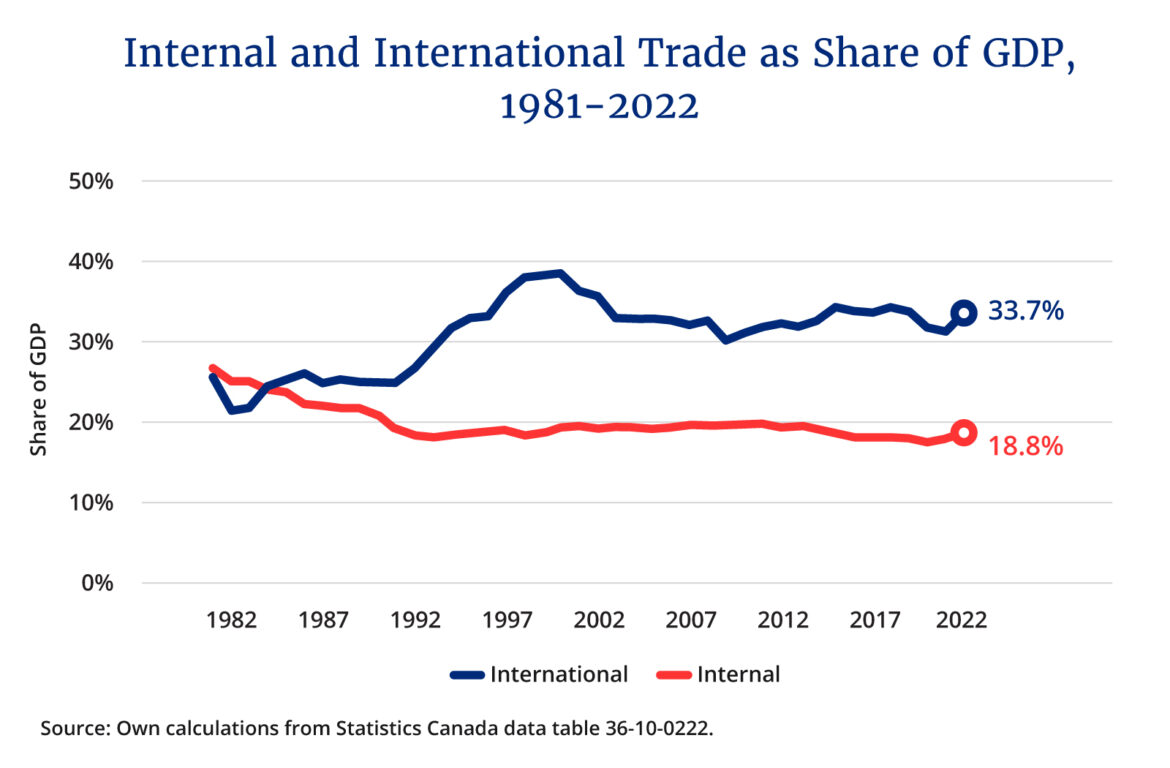

Trade allows Canada to maximize its economic advantages, but it needs good infrastructure. And at least for trade within Canada, we have a clear and costly problem. Since the early 1980s, interprovincial trade has declined and is now half of international trade.

If this was due to individual and business market decisions, it wouldn’t be a problem. But several barriers to the free flow of goods and services are at work.

Most of those are due to provincial governments having different rules, regulations, standards, and certifications. But another part of the problem is infrastructure, and the added costs involved when our road and rail networks fall short.

We need more funding, not less, for critical infrastructure. More funding for interprovincial highway capacity. More funding for expanding the national rail networks. More funding for seaways, ports, and airports. More funding for long-distance electricity transmission.

More for all of the above.

In recent years, we’ve seen precisely the opposite.

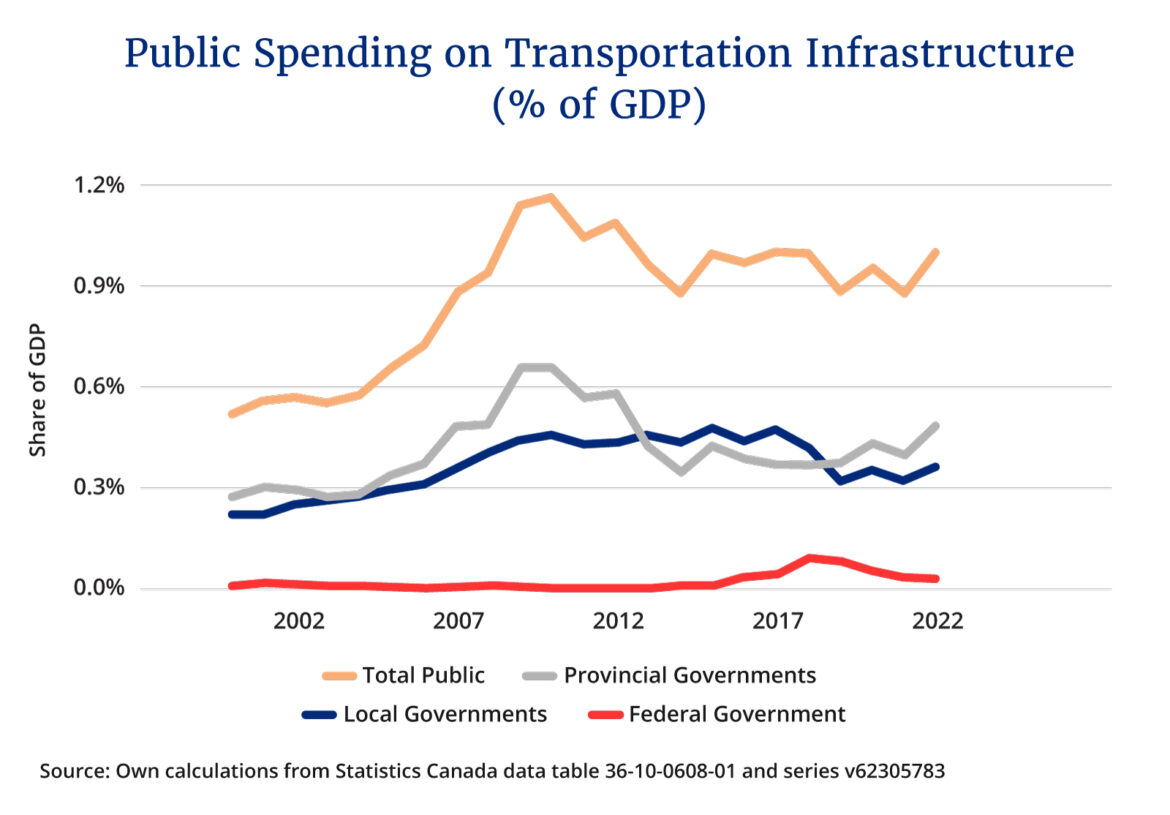

Canada’s federal, provincial, and local governments spend less on transportation than two-thirds of what the U.S. does as a share of our respective economies. And after rising substantially between 2004 and 2009, our public spending on transportation infrastructure fell by roughly 0.2 percent of GDP. That may not seem like much, but it means roughly $5 billion less per year for critical infrastructure. To match the U.S., we’d need to spend about $17 billion per year more.

Reduced direct federal spending is not the main cause of the decline, to be sure. But since 2018, provincial transportation infrastructure spending is up while federal spending is down. In 2022, according to the latest data, federal expenditures amounted to just $800 million. And, according to Statistics Canada, most of this investment is negated by an estimated $670 million in depreciation of existing infrastructure. Net federal infrastructure investment is therefore nearly zero.

Of course, some provincial spending depends on federal contributions that share in the costs. We have issues there too.

First, funding squabbles between governments are frequent. Consider recent disputes over financing improvements on the Chignecto Isthmus between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, despite clearly being an interprovincial project. Similarly, the development of the Ring of Fire in Ontario has faced major obstacles.

Second, and perhaps more troublesome, the federal government consistently fails to spend available funds. Last year, for example, of the $1.1 billion available in the National Trade Corridors Fund (meant to help fund roads, railways and airports) the federal government spent only $219 million. The year before that, there was $339.4 million available but only $233 million was spent. Before that, $463 million available, $164.6 million spent. In fact, from what I can tell, every single year underspent the available funds considerably.

Improving internal trade with more and better infrastructure could boost our lagging productivity. While not cheap, the gains are considerable.

To give just a hint of the potential for economic gains, consider improving infrastructure just in Canada’s North. My colleague Professor Fellows and I estimate that if the quality of northern Canada’s infrastructure simply matched southern Canada’s, the present value of future economic gains might be on the order of roughly $100 billion.

Expanding transport infrastructure would also reduce increasingly real risks. Single events, for example, can sever interprovincial ties. Recall the 2021 British Columbia flood that almost turned the province into an island separated from the rest of the country.

There might also be political benefits. Prime Minister Diefenbaker campaigned quite successfully with “Roads to Resources,” which planned to expand road infrastructure to boost natural resource exploration and development.It’s worth noting that Diefenbaker’s initiative wasn’t exactly a resounding success, being quite limited in scope and ambition. However, the rhetoric tapped into an idea that remains pertinent. Deepening the physical connections between Canada’s diverse regions was then, as it would be now, about “a transcending sense of national purpose.”

Where might the money come from? There are plenty of options, including from both public and private sources. From the public, each federal gas tax point is about $600 million, for example. We could massively expand the National Trade Corridors Fund (and make it permanent) with a modest gas tax hike.Federal gas taxes have been flat at 10 cents per litre since 1995. If it merely increased with inflation, it would be 18 cents today. From the private, we could use trade corridors (championed recently by the Senate of Canada) to ease regulatory burdens on private infrastructure proponents. We could also use tolls to leverage private capital.

One thing is clear, though: backing away from new major road projects on ideological grounds points Canada in precisely the wrong direction.

Recommended for You

‘They’re voting with their eyeballs’: Sean Speer on the revealed preferences of Canadian news consumers

Kirk LaPointe: B.C.’s ferry fiasco is a perfectly Canadian controversy

‘I want to make Canada a freer country’: Conservative MP Andrew Lawton talks being a newbie in Parliament, patriotism, and Pierre Poilievre’s strategy

The state of Canada’s economy halfway through 2025