We focus a lot on Canada’s federal budget. Given its substantial size, much of that attention is, of course, well deserved. But collectively, provincial governments are nearly 50 percent larger. And together with local governments—a provincial responsibility—they are nearly twice the federal government.

Recently, there’s been a flurry of activity in this area. Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Alberta each tabled their fiscal plans last week, following British Columbia’s budget the week prior. Québec unveils its next week, and Ontario’s is also likely to come soon.

These fiscal plans offer valuable lessons for the country, but none more so than those of Canada’s two richest provinces—British Columbia and Alberta. They are each playing with fiscal fire. Both have rapidly increased spending. B.C. is financing this with borrowing, while Alberta is doing so with windfall resource revenues.

Both are risky gambles. One government makes big short-term bets while the other makes long-term ones. They are models for how not to prudently manage government finances.

British Columbia’s long-term bet

Let’s start with B.C. Spending has accelerated there since the province elected its NDP government in 2017.

According to an analysis by Ben Eisen and Joel Emes of the Fraser Institute published early last year, real per-person spending growth increased to 4.7 percent per year between 2017 and 2021. This is a big change from the 0.5 percent annual growth between 2000 and 2017. And this was not due to COVID, as they rightly excluded those expenditures from the calculation.

The trend of growing spending faster than population plus inflation is set to continue. B.C.’s Budget 2024 features a real per-person total expenditure increase of 1.8 percent. In addition, capital spending per person (again, adjusted for inflation) has accelerated even faster, rising by 27.1 percent in 2023 and an anticipated increase of 19.5 percent in 2024.

Such spending may be justified, of course. Every policy choice has pros and cons. But when rapid spending growth is financed by higher borrowing, long-term sustainability concerns arise. That’s B.C.’s problem, and it’s getting worse.

Since Premier Eby took office in 2022, the province has borrowed heavily. From a modest surplus of $704 million in 2022, the deficit is now projected to exceed $7.9 billion in 2024, with similarly substantial deficits in the years to come.

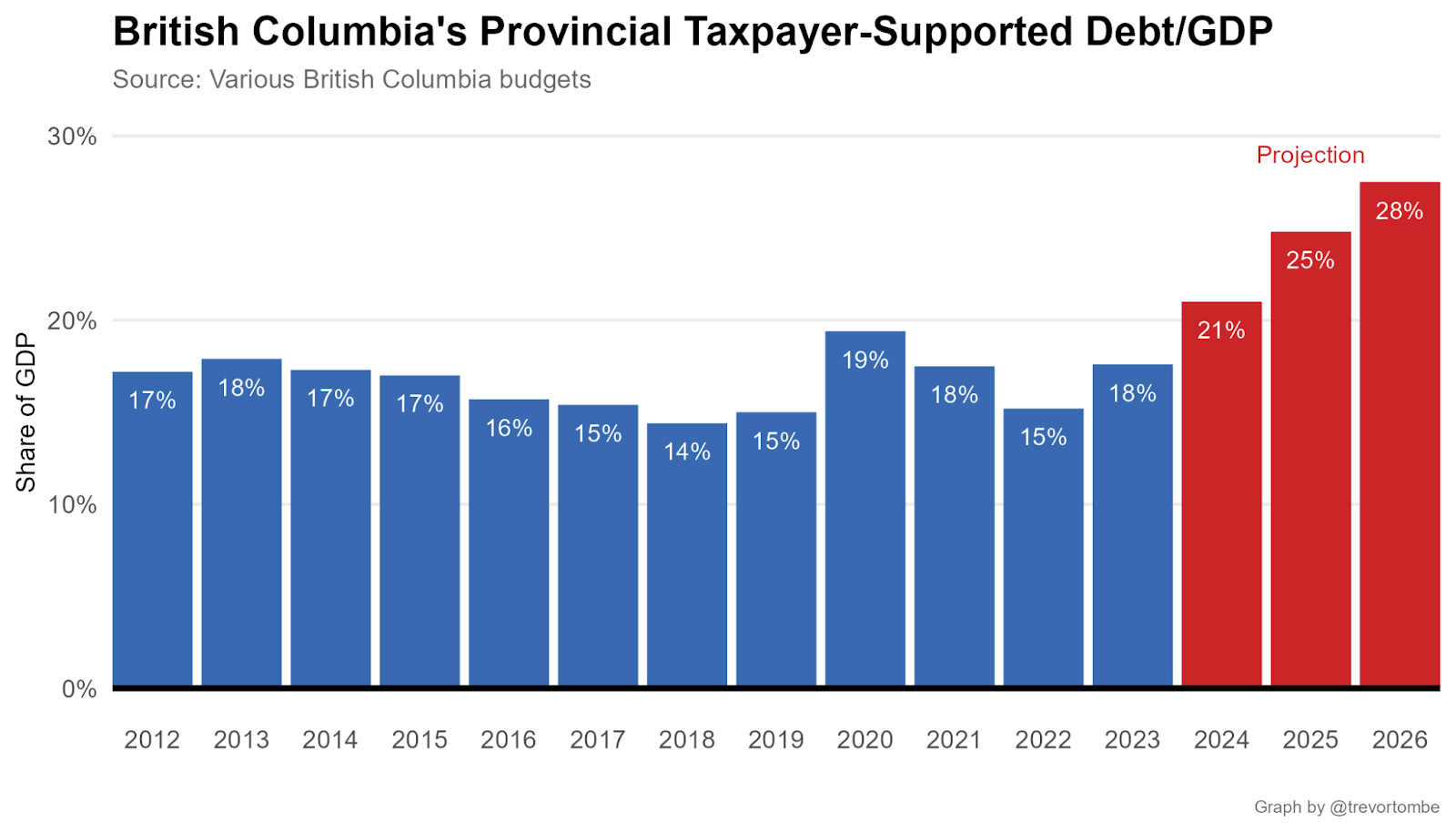

As a share of the province’s economy, which is often a more relevant metric, the province’s debt will increase from 15 percent of GDP in 2022 to 21 percent in 2024 and to 28 percent by 2026.

That’s a very large increase. For context, it’s similar to the federal debt increase, which absorbed most COVID-19 costs. In per-person terms, it’s a doubling from just over $11,000 in 2022 to nearly $22,000 by 2026.

Simply put, B.C.’s provincial debt is accumulating at a pace that cannot be sustained.

Most provinces face long-term fiscal challenges, to be sure. But B.C.’s are the largest. In my latest projections for Finances of the Nation, I estimate that B.C.’s long-run fiscal future is now bleaker than any other, including Newfoundland and Labrador, which normally holds such a distinction. To stabilize B.C.’s debt trajectory, I estimate revenue must increase or expenditures must decrease by 4.8 percent of GDP immediately and permanently.

That’s enormous. Imagine raising the provincial sales tax from 7 percent to 22 percent.

The province can manage its finances quite well for the foreseeable future, but something will have to give.

Alberta’s short-term bet

If B.C.’s risks are long-term, its eastern neighbour’s are short-term.

Many consider Alberta fiscally conservative. But this is not always the case.

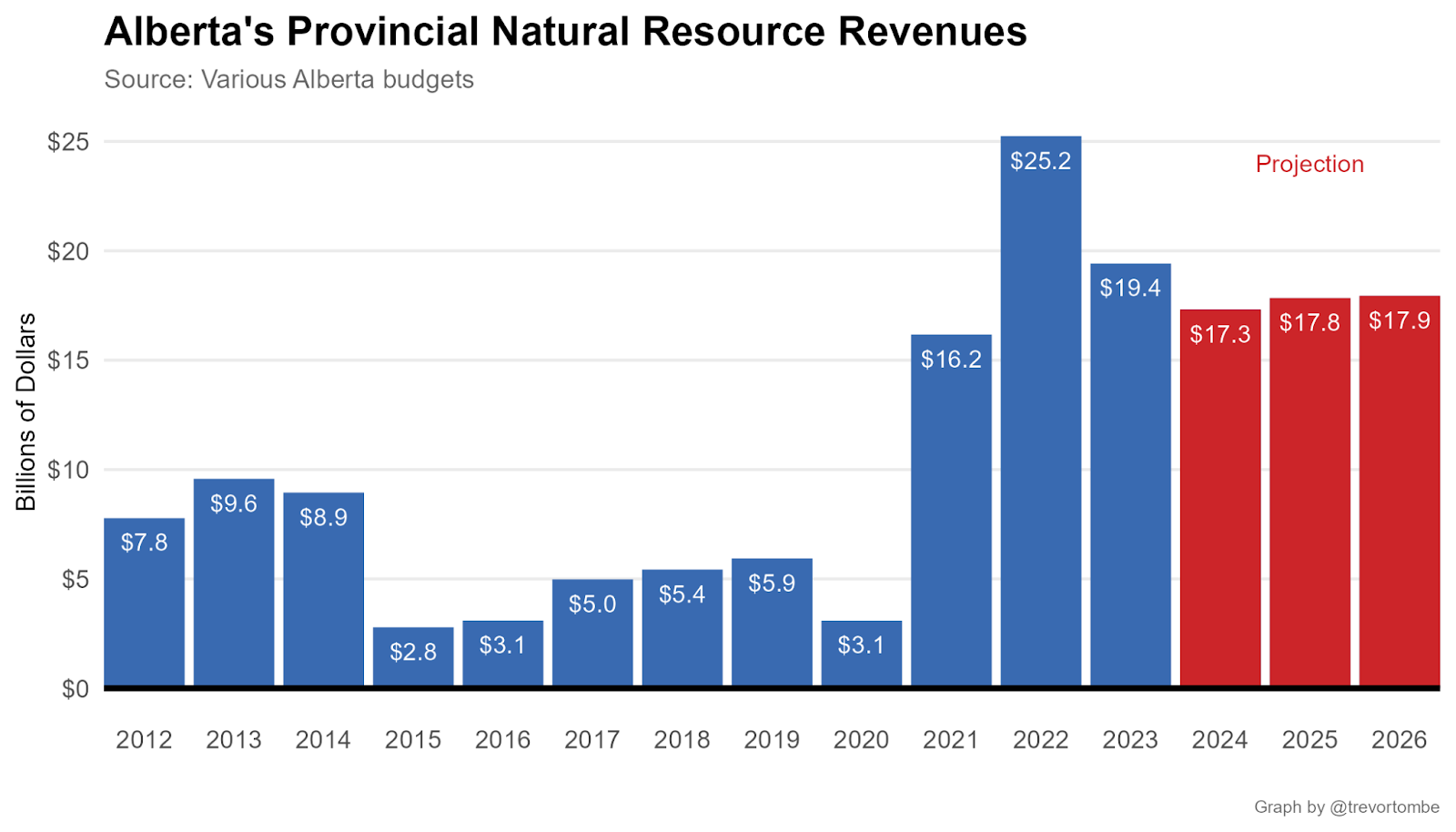

When Premier Kenney first set the fiscal plans for 2023, resource revenues were expected to be roughly $5.9 billion. They’ll now likely exceed $19.4 billion. Of that $13.5 billion surprise windfall, the province chose to spend $11.5 billion of it rather than use it to save or pay down more debt. This massive reversal of fiscal policy will continue through 2024. Alberta plans to spend over $73 billion this year, which is not only $10 billion higher than Premier Kenney’s original plans for 2024 but also surpasses Premier Smith’s own initial plans set last year by $3.5 billion.

Alberta has now seen a faster increase in provincial spending than it did during COVID. Faster even than when the previous NDP government first took office. That’s hardly a fiscally conservative approach to budgeting, and it puts Alberta in a very risky situation.

In 2024, Alberta needs $17 billion in natural resource revenues to balance its books. This significantly exceeds the $8.7 billion needed in 2021 (excluding COVID).

Alberta is riding the resource rollercoaster harder than ever.

Since 2000, the average annual change in oil prices has been over $14 per barrel. For Alberta, each dollar change is worth roughly $630 million to the government’s bottom line. The average yearly swing in oil prices is therefore today worth about $9 billion—equivalent to 2 percent of the province’s economy.

The risks both provinces are taking are choices that they have the luxury of making. Each province has a strong economy and fiscal capacity. They are the two richest provinces in Canada and governments in both provinces face difficult political pressures, especially B.C., with an election scheduled for later this year.

But we should be clear about what those choices are and recognize that neither is a particularly prudent approach. They’re both playing with fiscal fire. Should their bets fail to pay off, they may each be burned. Canadians everywhere should take note.

Recommended for You

The great fiscal–economic decoupling of Alberta

‘We’re back in the haunted house’: Danielle Smith’s multi-billion-dollar deficit problem

Why neither Carney nor Poilievre is rushing towards a snap election

Canada’s great refugee disaster