With inflation subsiding and poised to fall below three percent in 2024 and an economy that is slowing but not in recession, the Bank of Canada’s monetary policy of interest rate increases over the last two years appears to have successfully engineered a soft landing for the economy. Unemployment remains below six percent, wage growth appears to be slowing, and while GDP growth in 2023 was anemic, there were no two consecutive quarters of negative growth, meaning Canada averted a technical recession.

As the post-pandemic inflationary surge subsides, discussion has turned to the question of rate cuts to end the pain that has been caused particularly to mortgage holders and other borrowers. While the higher interest rates that Canadians have endured are low relative to the rates of the 1980s or 1990s, they are being felt harshly given that the decade prior to this increase saw some of the lowest rates in recent Canadian economic history. Calls for lowering interest rates have most recently come from the premier of Ontario, as well as economists.

There are really two separate questions to consider with respect to interest rate policy in Canada. First, should interest rates come down? Second, when should they come down? Indeed, even in the face of stubbornly core inflation and inflationary wage expectations, economists Jeremy Kronick and Steve Ambler have made the case for a rate cut by the Bank of Canada in April. Their argument hinges on the notable decline in inflation once more volatile components of the main CPI are stripped out, as well as the growing weakness of GDP growth going into 2024 notwithstanding the successful soft landing of 2023.

Given that the U.S. economy has performed even more robustly than Canada’s in the face of interest rate increases, much will depend on when the U.S. Federal Reserve begins to start cutting its rates. Ultimately, our central bank rate and interest rates in general will not get too far out of line with American ones given that our economy is heavily integrated with the U.S. While it is anticipated that the U.S. Fed will begin reducing interest rates in 2024—something made even more likely one suspects by the prospect of an election in November—it is unlikely it will cut rates before April given that even chair Jerome Powell has said it is unlikely to occur.

All of this aside, the overarching question facing Canadians is where can we expect interest rates to settle down at once victory has been declared on the war against inflation? Here we can draw some insight from the long-term performance of the Bank of Canada rate and the Canadian economy since the taming of the last great inflationary surge of the 1970s and 1980s. The period since 1990 represents a distinct economic era from pre-1990 given that it was marked by the taming of inflationary expectations and economic liberalization via trade agreements and globalization that sparked a new era of growth for the Canadian economy. This was also the era that saw the Bank of Canada adopt the 2 percent inflation target. Evidence from this era may provide an indication of where the bank rate is going to settle down at.

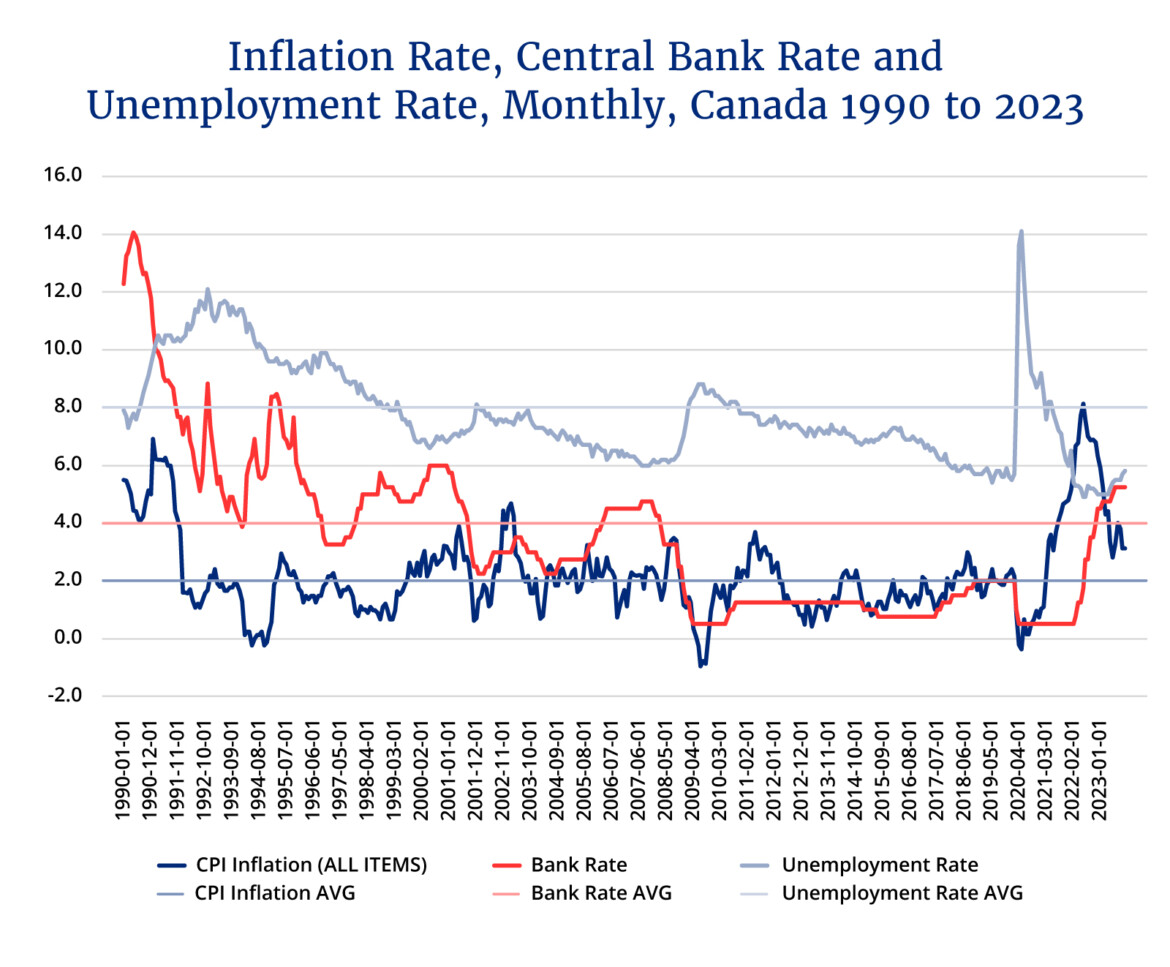

The accompanying figure uses Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) from the St. Louis Fed to plot monthly data from 1990 to 2023 for three variables: the CPI (all items) inflation rate; the central bank rate; and the unemployment rate. These variables are all related when it comes to monetary policy given that restrictive monetary policy designed to slow the economy down and bring down the rate of inflation would also be correlated with a rising unemployment rate. Along with the monthly variable plots, what has also been plotted is the average for each variable over the 1990 to 2023 period.

The resulting averages are striking. First, inflation over this period has indeed averaged 2 percent. At the same time, it has been accompanied by an average central bank rate of 4 percent and an average unemployment rate of 8 percent. Notwithstanding fluctuations and short-term trends, on average during this period, the central bank rate has been approximately twice that of the inflation rate, and the unemployment rate double the bank rate. Put another way, to keep inflation at about 2 percent, you need a bank rate of 4 percent and sufficient slack in the labour market resulting in an 8 percent unemployment rate.

On the one hand, a 2-4-8 rule summarizing a longer-term empirical relationship between inflation, the bank rate, and the unemployment rate may seem like an arbitrary, exceedingly simplistic, and coincidental relationship. On the other hand, we are currently at 3 percent inflation, 5 percent bank rate, and 6 percent unemployment, suggesting that relative to the long-term average performance, there is still substantial inflationary pressure in the Canadian economy. To bring us down to 2 percent inflation may require the bank rate to stay higher for longer than many would like.

More to the point, the accompanying figure suggests the ultra-low interest rates of the last decade are indeed an aberration. Those expecting the bank rate to go back down to 1 percent once declines begin are in for a big shock. Indeed, even the Bank of Canada is on the record stating that the very low rates from 2008-09 are unlikely to return and will lead to a world where they are higher than we have grown accustomed to. However, if you need empirical evidence based on historical averages from even before 1990, a bank rate of 4 percent is probably a realistic expectation of what the future will bring.

Recommended for You

Does Japan’s election lay the groundwork for a Liberal majority this spring?

Tale of two provinces: Alberta gains jobs as Ontario loses 67,000 positions

A new playbook for Canada-U.S. relations: How the University of Calgary’s New North America Initiative aims to reshape the continent’s politics

Canadians love big government—even though it’s holding us back