Canadians’ ignorance of our own history is a pervasive and regrettable problem. The Hub is pleased to play a small part in attempting to turn this tide by presenting a weekly column from author and historian Antony Anderson on the week that was in Canadian history.

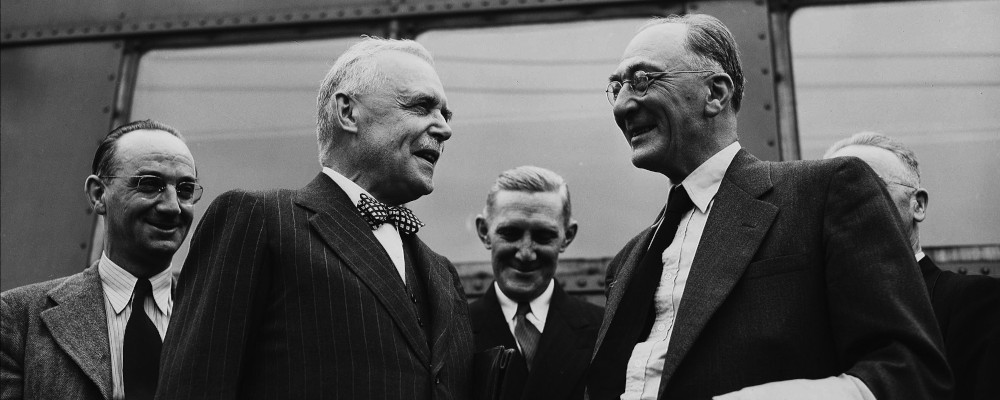

February 1, 1882: Louis St. Laurent is born in Compton, Quebec

Our first truly internationalist prime minister started his journey in a tiny village in Quebec where his family’s general store was a local gathering place, and where he grew up speaking French with his father and English with his mother, effortlessly embodying what was then the fundamental and divisive Canadian duality.

Shy, intelligent, watchful, he rejected his parents’ hopes that he enter the priesthood and instead became a successful corporate lawyer in the provincial capital, going on to argue cases before the Supreme Court and serve on a landmark royal commission. He made a name for himself, caught the eye of various Liberals, and then war and death intervened to convulse his comfortable progress.

In the midst of grappling with the nightmare issue of conscription, Prime Minister Mackenzie King lost his Quebec lieutenant Ernest Lapointe to cancer in November 1941. Quebec was terra incognita to most anglophones, so he canvassed local opinion and found himself turning to someone he barely knew, St. Laurent, who in turn could not refuse the call of duty. He joined the cabinet in December 1941. This was perhaps one of King’s most far-reaching decisions. St. Laurent was no placeholder.

When the cornered PM finally introduced overseas conscription, causing two ministers from Quebec to resign, St. Laurent held firm and supported King. This was heresy in his home province. According to a journalist confidante, the prime minister felt his new justice minister had not just saved the government but Confederation itself. King saw the future of the Liberal Party.

In August 1948, St. Laurent took the Liberal leadership, a seeming amateur in the political trenches. But, imbued with the social graces of small-town life, he proved to have just the right touch with voters. The press dubbed him “Uncle Louis.” The voters bestowed two impressive majorities in 1949 and 1953. He turned out to be a brilliant manager of policies, events, and egos. The leader who was so often dismissed as a distant chairman of the board would prove to be transformational.

Some of these changes he cared deeply about, some he introduced because hungry cabinet colleagues had pressed for them. This included introducing hospital insurance and establishing the Canada Council. His government launched the St. Lawrence Seaway and the Trans-Canada Highway, mega infrastructure projects that captured the optimistic, expansive post-war frame of mind. His true achievements were more fundamental.

St. Laurent amended the Constitution so that the federal government could at last make changes in areas of federal jurisdiction without going through London. He abolished the right of Canadians to make appeals to mother country’s Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, so Canada’s Supreme Court was truly and finally supreme. He began—quietly—to erase the word “Dominion” from government usage and documents; many in his generation thought this word (invented by Canadians for Canadians) smacked of immaturity. He appointed the first Canadian-born governor general. He brought Newfoundland into Confederation—or should that be, he presided over some rambunctiousness and lubricated voter persuasion which still only persuaded a slim majority to come on board. That was the game at home.

Out in the world, St. Laurent made Canada’s presence felt—within middle power limits—and respected. He was a staunch supporter of NATO. Indeed he had called for a Western military alliance in 1947 but this Canadian initiative was ignored by allies until the Russians overwhelmed Czechoslovakia. Then everyone grasped the need to contain the spreading Iron Curtain. After an initial dose of hesitation (he didn’t think this was Canada’s war) St. Laurent sent Canadian troops to join a UN force defending South Korea from invading North Koreans. He backed his foreign minister, Lester Pearson, to the hilt during the Suez Crisis when Pearson refused to support Britain and France in their assault on Egypt to salvage their rusted imperial glories. If anything, Pearson had to restrain an infuriated St. Laurent who burst out in Parliament during a debate where he stated, “the era when the supermen of Europe could govern the whole world is coming pretty close to an end.” Pearson could not have triumphed at the UN—or won the Nobel Peace Prize—without St. Laurent’s unflinching backing.

In the midst of all this, St. Laurent suffered bouts of depression. By 1956 these waves seemed deeper and darker. By his mid-seventies the razor-sharp focus was unsteady, dimmed by apathy. He knew it was time to leave and talked about stepping down. But he was still the party’s great electoral asset. A cold-blooded cabinet minister said they would “run him stuffed” if they had to. So St. Laurent, done in by his sense of duty, made the great mistake of his political life and stayed one election too long.

In the 1957 contest, he went through the motions. The kindly uncle had turned into a cranky bore. His opponent, Conservative leader John Diefenbaker, was on fire. Still, after 22 years of Liberal rule, everyone expected more of the same. A tiny proportion of voters went on to deliver one of the great upsets in Canadian history. Untouchable Liberal heavyweights went down to defeat and the upstart Diefenbaker eked out a stunning minority of seats; though even a diminished St. Laurent had won the popular vote, if only just. St. Laurent retired from politics after this, returned to Quebec City to practice law once again, and essentially vanished from view. He never felt the need, in or out of power, to draw attention to himself. He did not write any memoirs. A former aide has written the one full-length biography we have on him. He died in July 1973.

There’s a part of me that doesn’t care which statues get torn down, what streets get renamed. These are spasms, part of an endless argument over the traces that have survived for now. What disturbs me more is the perpetual vortex of forgetting. How can one citizen achieve so much and then just disappear from the vernacular? Is this a quirk of the immensely fractured and distracted 21st century? Is it a measure of democratic genius that our amnesia ensures we don’t worship mere mortals?

I don’t know the answers to any of these musings. What I do know is that one day I will travel to Compton, Quebec to see St. Laurent’s grave and say a quiet thanks.

Recommended for You

The Notebook by Theo Argitis: Mark Carney’s first major tests

The Weekly Wrap: Trudeau left Canada in terrible fiscal shape—and now Carney’s on clean-up duty

‘Another round of trying to pull capital from Canada’: The Roundtable on Trump’s latest tariff salvo

‘We knew something was coming’: Joseph Steinberg on how Trump is ramping up his latest tariff threats against Canada