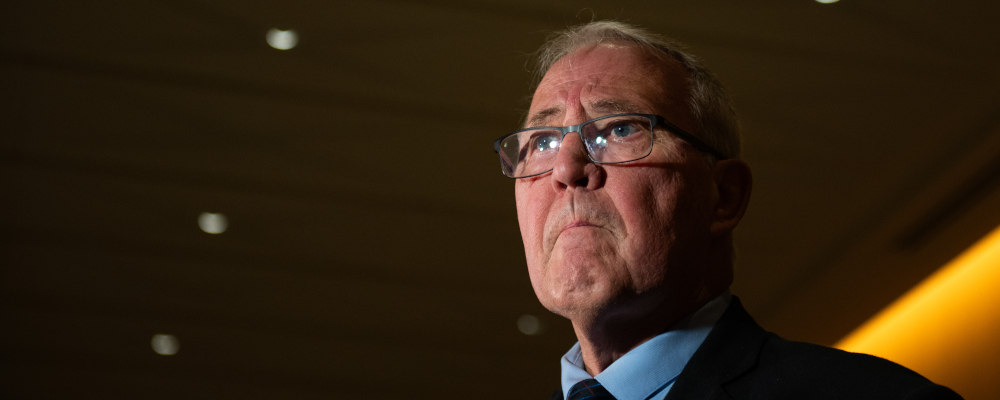

The following is drawn from testimony delivered by Richard Shimooka on February 14 to the Standing Committee on National Defence on the topic of transparency within the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces.

Thank you for letting me speak today to the committee on the topic of transparency within National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces. It has relevance to me for a variety of reasons, but none so much as it deeply affects my ability to undertake research in defence policy and strategy in Canada.

My focus is on chronicling contemporary defence and foreign policy, and the most significant tools I possess in doing so are the Access to Information Act system (ATI) and interviews with policymakers. I’m going to focus my discussion on how these areas have changed in the past twenty years and affected transparency.

In Canada, I feel like this is a gap in our intellectual landscape, especially when you compare us to our allies like the United States and the United Kingdom. Those countries’ national security communities and civil societies value such research as an important function and it is comparatively much more vibrant than in Canada.

Why is it important? The traditional and most immediate view is that this is an important form of independent accountability and oversight of government. Yet there are other benefits. One of the more significant failings of our system of governance is the lack of institutional knowledge. The history that guided a policy’s creation is frequently forgotten, even if it remains in place. Filling that gap can assist policymakers in crafting better policies in the future.

Finally, such research can benefit the government to better communicate policies to domestic and foreign audiences; even the best public affairs department or the most talented minister will be limited in their opportunity to explain these contextual factors, while analysis by outside researchers can be a critical information source to interested parties and may help advance policy goals.

Unfortunately, undertaking public policy research has become increasingly challenging over the past two decades. I started around 2003 when transparency and oversight were heavily influenced by the fallout of the Somalia Inquiry. It revealed systemic efforts by the department to obfuscate aspects of the crisis, which extended to ATI. The lack of transparency forced the department to reform how it operated for the next decade.

Over the past twenty years, ATI has become an increasingly ineffective system to obtain useful information on a timely basis. In 2002, relatively straightforward ATI queries would generally provide a good return of documents. A set of ATIs I used to study the 1996 Intervention in Zaire provided over 2,000 documents with a very high level of complexity and included a large number of foreign confidences, advice, and sensitive information. The original request took about a year to be released and provided an in-depth view of what occurred during that operation.

This would be unheard of today.

The amount of pages of documents has decreased year on year, and officials frequently employ highly restrictive interpretations in an effort to suppress the disclosure of some documents—or even claim that no such records have been found. In other cases, requesters are advised that the scope of the request is too broad and forced to truncate their query. Finally requests frequently take years to be fulfilled, significantly diminishing ATI’s value as a research tool.

Not all of the reasons for this situation are necessarily intentional. The ATI system today relies heavily on regular departmental staff to assess documentation for release—the same ones that are already overburdened with their day-to-day work. It is far from an ideal approach to handling ATI requests.

Concurrent with the ATI system’s enfeeblement, there has been a consistent effort to curtail officials’ ability to discuss policies with interested parties. In the years after the Somalia inquiry, DND employed a fairly liberalized communication policy and access to officials was fairly good. One of the most helpful aspects was that the department made available subject matter experts to discuss specific areas. However, around 2005, the policy changed dramatically. Part of it was due to the belief that the War in Afghanistan required “message discipline,” but there was also a preference by the Harper government to centralize its communication strategy. Access to officials was curtailed and replaced by superficial media response lines from public affairs representatives.

Furthermore, the ability to maintain working relationships with officials has become increasingly strained. The most serious rupture occurred after 2015 when Admiral Mark Norman was charged with breach of trust, and members of the Future Fighter Capability project were forced to sign a gag order. These events had a serious chilling effect on the bureaucracy, as individuals felt fear of the potential consequences surrounding talking outside of government. While some of that fear has dissipated over time, there still remains a significant reluctance to speak with candour on major issues.

So where are we today?

Overall, I believe the poor state of transparency in defence has largely been counterproductive for the government, resulting in the very outcome they wanted to avoid. Public understanding of the military is at an all-time low. This is in part due to the lack of open information available and the adversarial relationship that has developed between the government and outside bodies over access to information.

Unfortunately, I do not have an easy solution to this problem. There is a deep-seated view that the current approach is the only way to successfully manage public relations. Seeing past the immediate situation and a radically different future is a tough sell to any government. I fear that it will require another Somalia-scale scandal to impel a government to shift its behaviour, which will benefit no party or the country as a whole.

Recommended for You

The Notebook by Theo Argitis: Carney’s One Big Beautiful Tax Cut, and fresh budget lessons from the U.K.

Christopher Snook: Is Canada sleepwalking into dystopia?

Rudyard Griffiths and Sean Speer: The fiscal hangover from the One Big Beautiful Bill hits Canada

‘A fiscal headache for Mark Carney’: The Roundtable on how Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill could affect Canada