Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, an eloquent voice for the Old Tories, came into being around 1820 when Mr. Blackwood fired the rather hopeless editors and took charge of the monthly himself. “The Maga,” as it came to be known, was meant explicitly to compete with the Edinburgh Review—the darling of the Whig establishment, which seemed to have been in power forever.

“The Maga” did not waste time; it promptly set about making itself obnoxious, and winning the outrage of respectable, Whiggish intellectuals in London and elsewhere. “Christopher North,” the nominal, pseudonymous editor (he was more formally the professor of moral philosophy at Edinburgh) said this about Francis Jeffrey, his illustrious Review rival editor: “He hates me, no doubt, in a small toothy way, as a rat hates a terrier.”

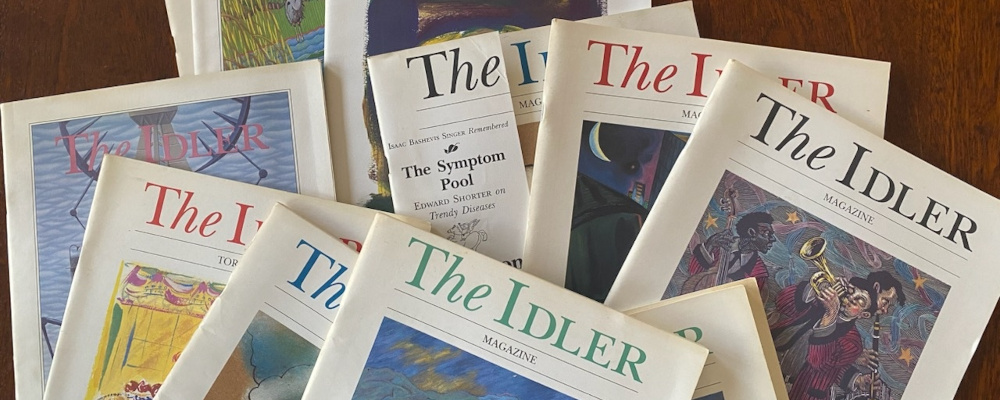

It was with a similar desire to be naughty and offensive, and perhaps also sophisticated, and spiritually Tory in the face of Canada’s perpetual “Liberal and Progressive” elites, that The Idler was founded at the end of 1984. It took its name from the periodical essay of Samuel Johnson, and by a crazy coincidence, the presses rolled on our first issue on the 200th anniversary of Dr. Johnson’s death, precisely to the minute. (This we realized only several weeks later.)

This attitude was clinched by our motto, “For those who read.” Note that it was not for those who can read, for we were in general opposition to literacy crusades, as, instinctively, to every other “good cause.” We once described the ideal Idler reader as “a sprightly, octogenarian spinster with a drinking problem, and an ability to conceal it.”

It was to be a magazine of elevated general interest, as opposed to the despicable tabloids. We—myself and the few co-conspirators—wished to address that tiny minority of Canadians with functioning minds. These co-conspirators included people like Eric McLuhan, Paul Wilson, George Jonas, Ian Hunter, Danielle Crittenden, and artists Paul Barker and Charles Jaffe. David Frum, Andrew Coyne, Douglas Cooper, Patricia Pearson, and Barbara Amiel also graced our pages.

I was the founder and would be the first editor. I felt I had the arrogance needed for the job.

I had spent much of my life outside the country and recently returned to it from Britain and the Far East. I had left Canada when I dropped out of high school because there seemed no chance that a person of untrammelled spirit could earn a living in Canadian publishing or journalism. Canada was, as Frum wrote in an early issue of The Idler, “a country where there is one side to every question.”

But there were several young people, and possibly many, with some literary talent, kicking around in the shadows, who lacked a literary outlet. These could perhaps be co-opted. (Dr. Johnson: “Much can be made of a Scotchman, if he be caught young.”)

The notion of publishing non-Canadians also occurred to me. The idea of not publishing the A.B.C. of official CanLit (it would be invidious to name them) further appealed.

We provided elegant 18th-century design, fine but not precious typography, tastefully dangerous uncaptioned drawings, shrewd editorial judgement, and crisp wit. I hoped this would win friends and influence people over the next century or so.

We would later be described as an “elegant, brilliant and often irritating thing, proudly pretentious and nostalgic, written by philosophers, curmudgeons, pedants, intellectual dandies. …There were articles on philosophical conundrums, on opera, on unjustifiably unknown Eastern European and Chinese poets.”

We struck the pose of 18th-century gentlemen and gentlewomen and used sentences that had subordinate clauses. We reviewed heavy books, devoted long articles to subjects such as birdwatching in Kenya or the anthropic cosmological principle, and we printed mottoes in Latin or German without translating them. This left our natural ideological adversaries scratching their heads.

Finding readers turned out to be a snip, as we were at least potentially entertaining. It wasn’t entirely necessary to pander to vulgar tastes; only to write mischievous headlines. Our idle, philosophical attitude was consistently joyful, not ideologically grim. Thus, we had a huge advantage over the local competition.

But the Canadian “media” economy was set up, then as now, to perpetuate grimness. There were no subsidies for joy, but instead penalties for thought crimes that evolved into today’s political incorrectitudes. Interestingly, our artists, whom we cultivated in the same way as our writers, were loyal to The Idler for the same reason: there was no other place where they were wanted.

Nothing much has changed, with the possible exception of technology, in the four decades since. The Hub is among several online presences in conflict with the brain death that continues to constitute the Canadian identity. It is one of the tiny cells that is twitching.

Making a buck

By luck, after producing the first issue entirely at my own expense, and distributing illustrated handbills to promote it, I awoke one morning to discover that literary editor William French had actually given the magazine prominent, enthusiastic coverage in The Globe and Mail. (He was an old-fashioned liberal, after all, with an open mind.) Soon, we were selling more than a thousand on newsstands, and had the largest foreign circulation of any Canadian magazine, I recall (thanks to five readers in Buffalo).

Over the next decade, we gave many Canadian writers their start and elevated a few foreign “big names” (like journalist and satirist Malcolm Muggeridge and the famous jailbird and Czech author Václav Havel). We also attracted—for a while—an intelligent furniture manufacturer and Holocaust survivor, Manny Drukier, who had the clever idea of starting a pub downstairs from our Toronto office, in the building he owned. This way, he reasoned, he’d be able to recover the modest wages he paid us. It was like putting up a sign that read, “Interesting people, please assemble here.” It also secured the curious intrigue we had instigated between Catholics, High Anglicans, and Jews, who were more welcome in our liquid environment than fashionable atheists.

While The Idler Pub certainly helped on the revenue side, we still had a wee problem, which was making a profit. Although we were circulating in excess of what any Canadian “literary magazine” had ever done, we still carried no advertising.

“Later, to shut us up, they gave us some chump change.”

The book publishers, whom we thought would be our natural market, went to some trouble ignoring us, as we multiplied reviews in “Read & Remarked” (our showplace for Gerald Owen, our learned public reader or “Anagnostes”). They were of course themselves chiefly dependent on the killjoy the Canada Council for the Arts, and other institutions of the vacuous Left, which also were not giving us any money.

We hit a little goldmine with a house advertisement that declared, “Subscribe to Canada’s 97th best literary magazine,” because 96 had received generous grants from these government cultural agencies. Only The Idler and The Chesterton Review (then published out of Saskatoon) were spurned. Later, to shut us up, they gave us some chump change.

Through Mr. Drukier’s efforts, however, we received ads from several of his industrial suppliers. I designed the mottoes and typography. I still remember my masterpiece: “Mampey Screw Works: None better! Check it out.” The client had declined “Memorable Screws.”

Then we invented “Idler to Idler,” a section of classified ads at the back of the magazine, which suddenly appeared, at Manny’s suggestion. I made up the first few dozen implausible entries. For instance: “I’ve got Spanny. You had him tied to a pillar at Dufferin and Bloor. Leave $250 in Druxy bag at Greyhound terminal locker 6, or Spanny is no more.”Or, “We met on Lufthansa, fell in love at JFK, lost each other at Terminal 1. Please call Jerry in Bramalea.”

Even these received “jokative” responses, and by next issue we received some genuine small ads, for which we had to assign genuine pigeonholes. We also launched the imaginary “Thelma Fowler,” an opinionated small advertisement manager, who was just one of the products of our ingenious copy editor, Elaine Duffy. The style caught on wondrously. The leading section was, of course, “Amours and Companions,” but miscellaneous “literary and scientific” requests suggested plenty of readers had been starved of community.

I estimate that, through Idler to Idler, and The Idler Pub, we were responsible for quite a few marriages as the ’80s moved along, mostly between the sort of couples who would prove fertile, and whose children must be approaching forty today. But swelling the population had not been among our initial purposes.

The end of the line

Towards the end of 1993, all our little debts were called in with the chickens, and we went tits up. There was one last sad Christmas party in The Idler Pub.

I haven’t invidiously named a few of our young contributors because several have managed to survive and even prosper in the “liberal and progressive” mass media, since. They have done so by abandoning the character they had once displayed and, I think, selling out. Still others have blown away with the winter snow. Even the stalwarts, with the passage of time, die one by one—like my patron, Manny, and my co-editor, Gerald, just the other day. May they rest in peace.

Aside from such appalling “facts of life,” was the experience worth it? It was. Given world enough and time, would I try it again? Of course I would.

Recommended for You

Sean Speer: Maybe Ron MacLean is the one who needs to go

Evan Menzies: Calgary at 150: Why is it so hard to celebrate our history?

Laura David: Red pill, blue pill: Google has made its opening salvo in the AI-news war. What’s Canadian media’s next move?

Falice Chin: The ‘wild and weird’ Calgary Stampede