DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic wellbeing. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of Centre for Civic Engagement.

The current state of Canada’s military and defence spending has been the subject of international criticism and a source of growing isolation from key allies. In a world of evolving geopolitical tensions and new and emerging threats, Canada’s underinvestment in national defence represents a major vulnerability.

Canadian policymakers seem to increasingly understand this point. Last week, former Conservative defence minister Jason Kenney was critical of his past government for failing to boost defence spending. However, while the recent federal budget earmarked incremental spending—though it was back-end loaded—Canada will still fall short of the NATO target of 2 percent of GDP.

One of the inherent challenges to policy thinking concerning Canadian defence policy and military spending is that, as previous auditor general reports have noted, it’s quite challenging to understand the state of defence spending due to various factors, including the Department of National Defence’s poor procurement record and the complexity of its accounting model.

The purpose of this DeepDive is to situate recent trends with respect to defence spending in a historical context as well as to discuss the state of Canada’s military capabilities and present some of the challenges that the Canadian government will face as it seeks to increase defence spending in an increasingly turbulent world.

What is the 2-percent target?

Historically, Canada was a relatively large spender on national defence. After the end of the Korean War in the early 1950s, Canadian military expenditures peaked at over 7 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) before steadily falling to roughly 2 percent in the 1980s.

Things, however, began to change with two episodes of fiscal consolidation, first under the Chrétien government in the 1990s and then under the Harper government in the 2000s. As a result, defence expenditures fell from 2.11 percent in 1986 to roughly 1 percent of GDP by 2014. At the same time, the size of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) was cut by 30 percent from 90,000 active troops in 1990 to 62,000 in 2005. The force size has remained mostly unchanged ever since.

It must be noted that 2014 wasn’t just an important year for being a low point in post-Second World War defence spending. It’s also the year when NATO implemented its much-discussed 2 percent of GDP defence spending target.

The origin of the 2-percent target actually dates back to 2006 when the notion of such a minimum national spending goal was first mentioned in a NATO document. Yet, a spending pledge would not be formalized until the 2014 NATO summit in Wales, which came on the heels of Russia’s invasion of Crimea in the same year.

While the focus is often on the overall defence spending target, two spending commitments were actually made in the NATO Wales Summit Declaration. Specifically, NATO members pledged to spend both 2 percent of the GDP on defence while also ensuring that 20 percent of their defence budgets are spent on major new equipment purchases, including expenditures related to research and development. The overall goal of the two commitments was to ensure that all NATO allies recognized the need to:

reverse the trend of declining defence budgets, to make the most effective use of our funds and to further a more balanced sharing of costs and responsibilities. Our overall security and defence depend both on how much we spend and how we spend it. Increased investments should be directed towards meeting our capability priorities, and Allies also need to display the political will to provide required capabilities and deploy forces when they are needed.

While the spirit of the NATO commitment was laudable and necessary, the notion of spending targets is not without criticism. The main criticism is that while the 2-percent target may be beneficial as a political rallying point, it’s merely an input metric that tells us nothing about defence outputs like operational readiness, capabilities, tactics, strategy, and overall competency. Instead, critics argue that the alliance and its members should focus more on ensuring that there is adequate force planning, readiness, and fighting capability among alliance members.

A more recent criticism is that the 2-percent target itself is too low in an increasingly dangerous world. For example, Polish President Andrzej Duda has argued that NATO’s spending target should be upped to 3 percent of GDP, given growing concerns about Russian attacks on NATO members. Likewise, last week, U.K. Defence Secretary Grant Shapps stated that the U.K. government now believes that the NATO target should be 2.5 percent of GDP.

How much does Canada spend on defence?

Although the NATO spending pledges are not without controversy, they are, nevertheless, what alliance members agreed to and thus serve as a baseline for spending analysis. The question then is: how does Canada stack up?

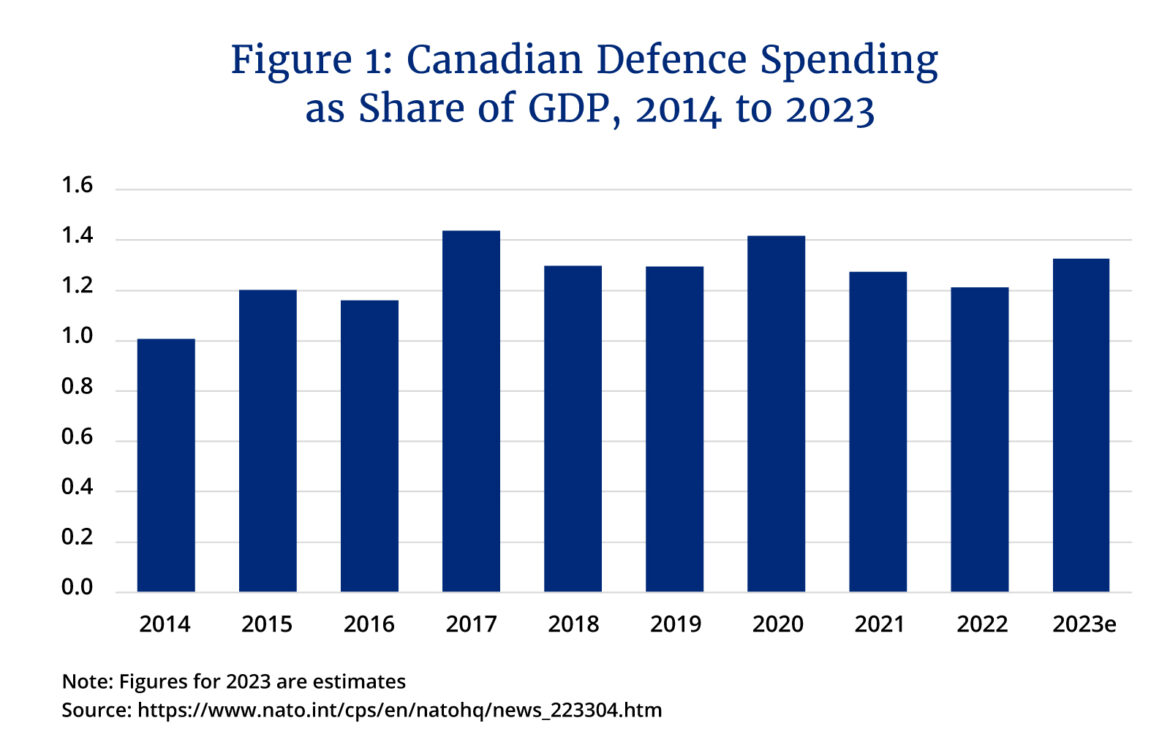

Figure 1 displays Canadian defence spending from 2014 to 2023 using figures directly from NATO. Across this period, defence spending has risen from 1 percent of GDP in 2014 to 1.3 percent by 2023. In real dollar terms (2015 constant prices), Canadian defence spending rose from $19.9 billion CAD in 2014 to $29.9 billion in 2023.All figures are in CAD. Some of the increased spending, however, needs to be taken with caution. Early in this period, NATO revised its definition of defence spending, making it more flexible to include spending items that were not previously allowed, such as veterans’ pensions and benefits. These definitional changes partly explain the increase in Canada’s absolute spending.

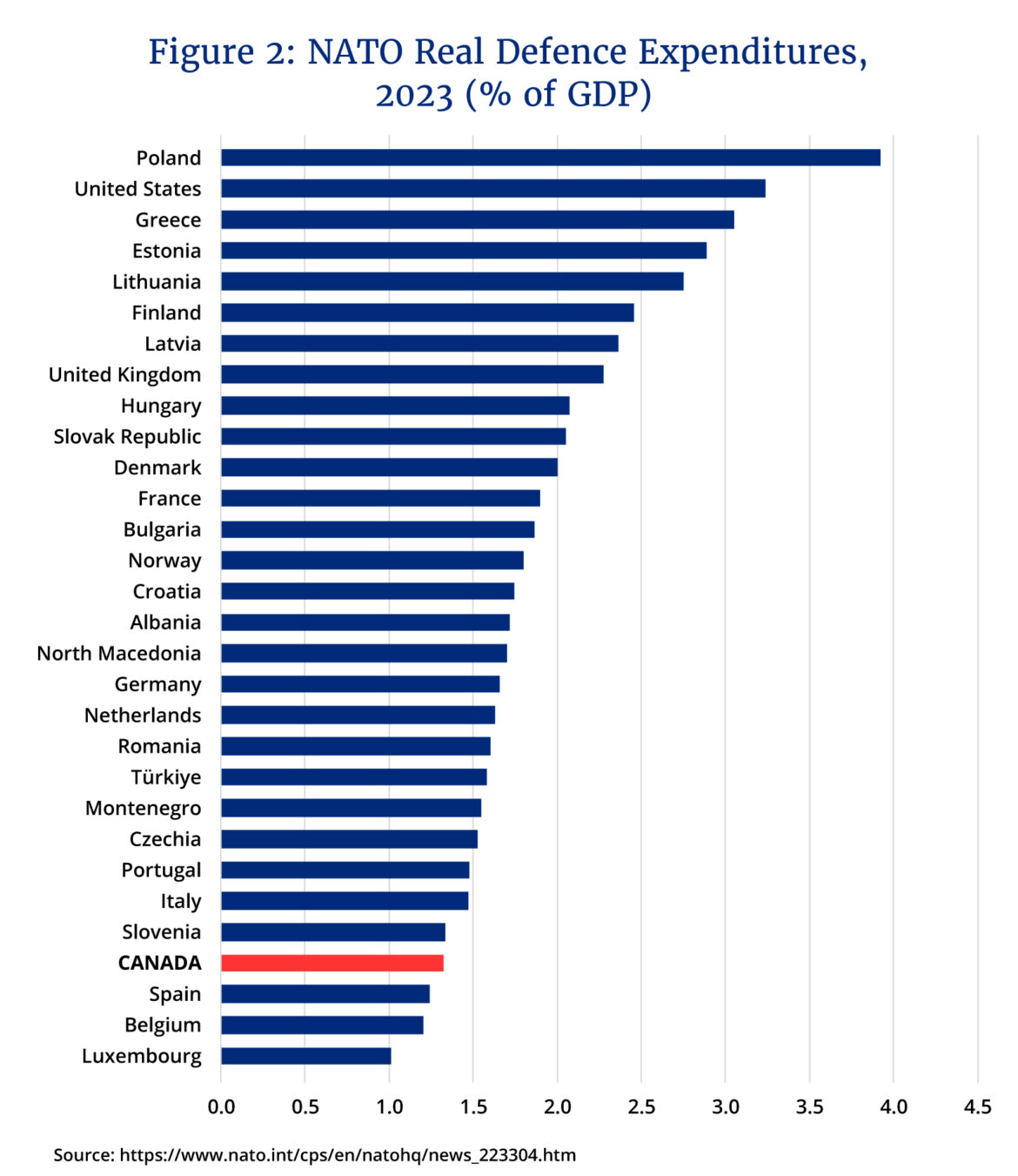

How does Canada compare to the rest of the NATO membership on defence spending relative to the size of their economies? As Figure 2 shows, quite poorly. Out of 30 NATO members for which there is data (Iceland and Sweden are not included in the NATO spending figures), Canada ranks the fourth lowest in terms of defence spending relative to the size of its economy, only ahead of Spain, Belgium, and Luxembourg.

Based on 2023 estimates, only 11 NATO members were meeting the 2-percent target. However, this is quickly changing, and it could mean that Canada will look even more like a laggard relative to alliance membership. In February 2024, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg reported that 18 alliance members, more than half, were on track to meet the 2-percent threshold by the end of the year, representing a six-fold increase since 2014.

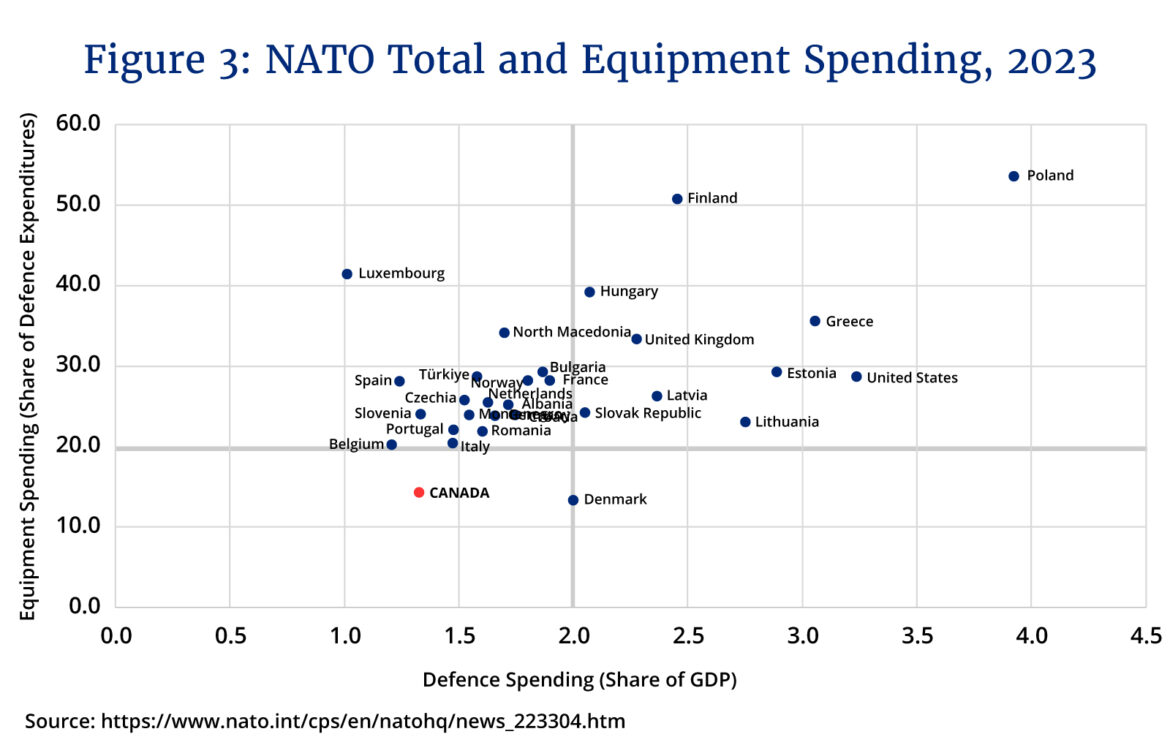

Canada’s performance is even worse if one considers both the 2 percent spending target in conjunction with the 20 percent of defence expenditures going to new equipment target. As can be seen in Figure 3, Canada is in the unenviable position of being the only NATO member in 2023 to neither meet its 2 percent overall defence spending target nor the 20 percent equipment spending target. Ten members currently meet both.

Although NATO lacks a formal accountability mechanism to ensure that members meet the targets, states that fall below them can suffer reputational costs and even become the target of naming and shaming exercises by other alliance members. In February 2024, for example, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg admonished Canada for not meeting the targets stating, “I expect Canada to deliver on the pledge to invest 2 percent of GDP on defence, because this is a promise we all made.”

The fact that Canada is the only member of the alliance to not meet either spending target represents therefore both a threat to its international reputation as well as its own defence and security. It prompts the obvious question: what would it have taken for Canada to at least meet the 2-percent target every year since 2014?

Using Canada’s defence spending levels and estimates of Canadian real GDP, we estimate that the cumulative real value of Canada’s NATO spending gap from 2014 to 2022 is approximately $150 billion (in 2017 dollars). That is to say, real spending on defence would have needed to be $150 billion higher in total between 2014 and 2022 to meet Canada’s NATO spending pledges in each year, or approximately $16.7 billion each year on average. To put this into perspective, based on the Parliamentary Budget Office’s Ready Reckoner tool, which provides estimates of revenue impacts of tax changes, a 1.5-percentage point increase to the GST produces an additional $15 billion in incremental revenues each year, less than what would be required to fund the average annual increase in real defence spending.

From spending to operational issues

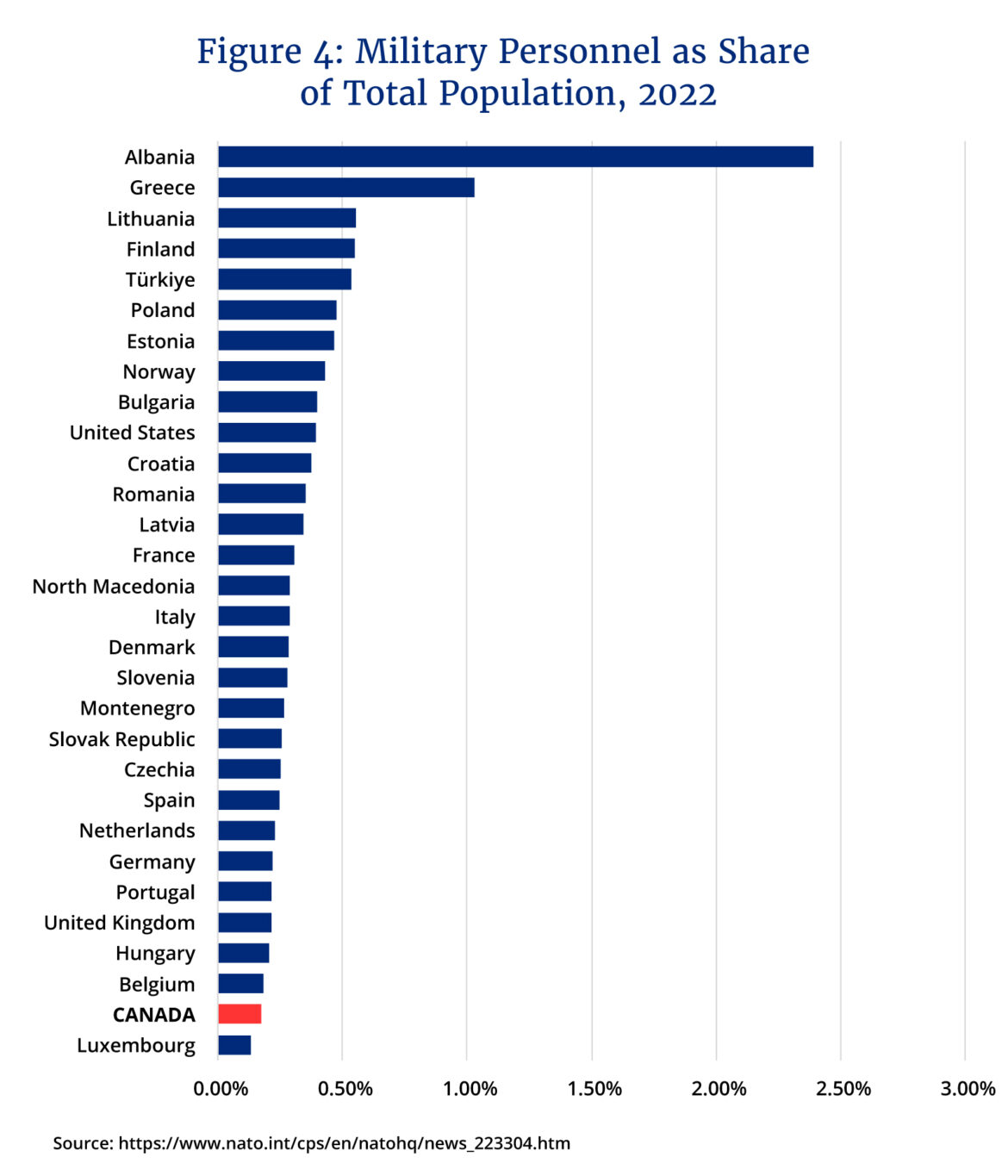

Canada’s defence spending woes are increasingly manifesting as operational issues. Consider first the total size of the CAF. According to estimates provided to NATO, Canada’s armed personnel stood just shy of 67,000 in 2023, making it the tenth largest force among NATO members. However, things look different if you consider force size relative to population. Figure 4 presents these estimates. Here we use 2022 military personnel figures to match with the most recent population data available for each member from the World Bank. When looking at military personnel as a share of the total population, Canada ranks second last.

Indeed, not only is the size of Canada’s armed forces small when scaled by population size compared to other NATO members, but internal documents from the Department of National Defence (DND) are also starting to raise concerns. For example, 2023 documents obtained by the CBC stated that the CAF were short 15,780 members when considering both regular and reserve forces relative to the government’s own targets.

More troubling in those documents was the internal assessment of equipment readiness. Regarding the navy’s frigates, submarines, arctic and offshore patrol ships, and maritime coastal defence vessels, 54 percent were deemed not serviceable, meaning that they were in no state to deploy. For the airforce’s fighters, maritime aviation, search and rescue, tactical aviation, and transport aircraft, 55 percent were not serviceable. Finally, in the case of the army’s armoured fighting vehicles, artillery, combat support vehicles, logistics equipment, combat support vehicles, and logistics equipment, 46 percent were not serviceable.

The report noted that the biggest challenge to having equipment serviced and ready to deploy is personnel, in addition to older equipment being more difficult to maintain. As The Hub’s defence expert Richard Shimooka has written: “[Recent funding announcements] are being layered onto a military that has haemorrhaged much of its key personnel. Many individuals, who are already overtasked, rightly wonder who will be there to integrate, operate, or sustain these new capabilities.”

To begin to address some of Canada’s defence spending and operational issues, the Trudeau government has pledged to increase defence spending through its 2024 budget and Canada’s recently released defence policy update titled Our North, Strong and Free, Canada’s first defence policy update since 2017’s Strong, Secure, Engaged.

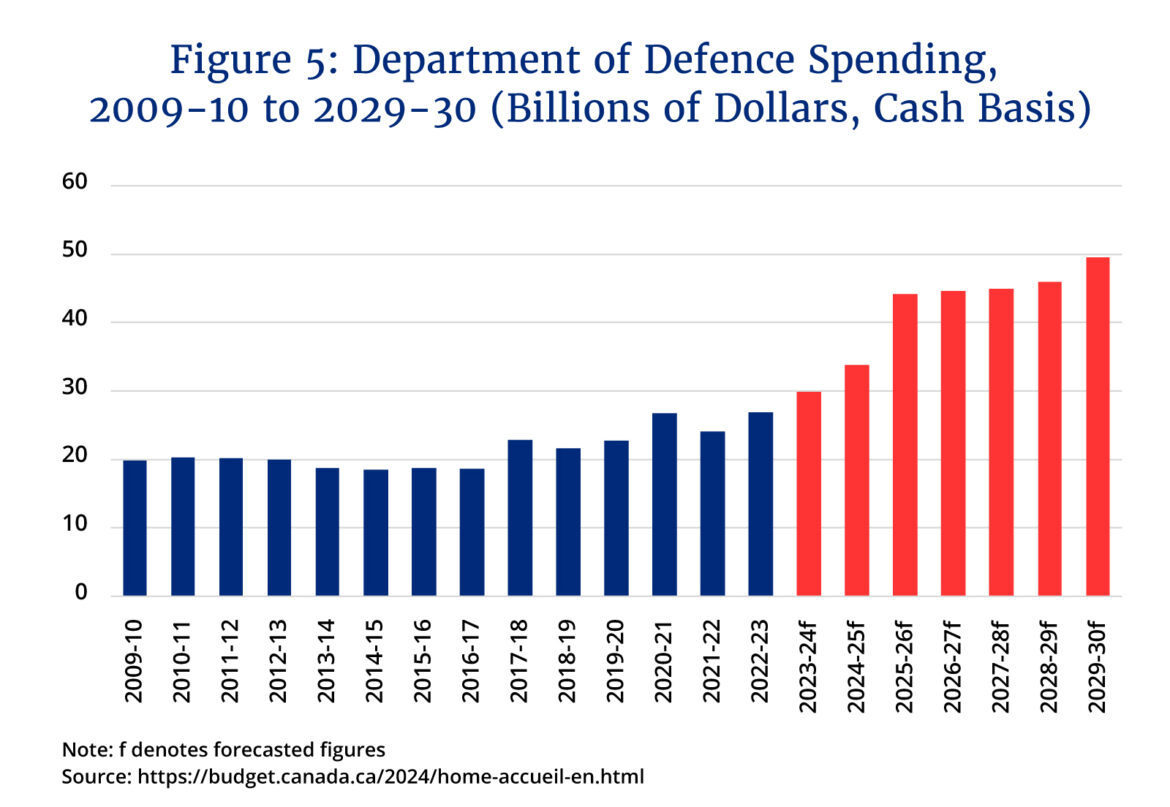

Beginning with the 2024 Budget, the government plans to increase spending directly for DND itself from $26.9 billion in 2022-23 to $49.5 billion in 2029-30 (see Figure 5). This increase includes commitments like $30 billion over 20 years for NORAD modernization and $11.5 billion over 20 years for Canada’s contribution to increasing NATO’s common budget and establishing a new regional office in Halifax for NATO’s Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic. It should be noted that based on the nominal GDP projections in the budget, the 2028-29 spending of $46 billion is estimated to be about 1.3 percent of Canada’s projected GDP.

The government’s recently released defence policy similarly doesn’t include a plan to meet NATO targets. Indeed, the policy document anticipates spending 1.76 percent of GDP by 2029-30 while indicating that it will meet the 20 percent equipment spending target.

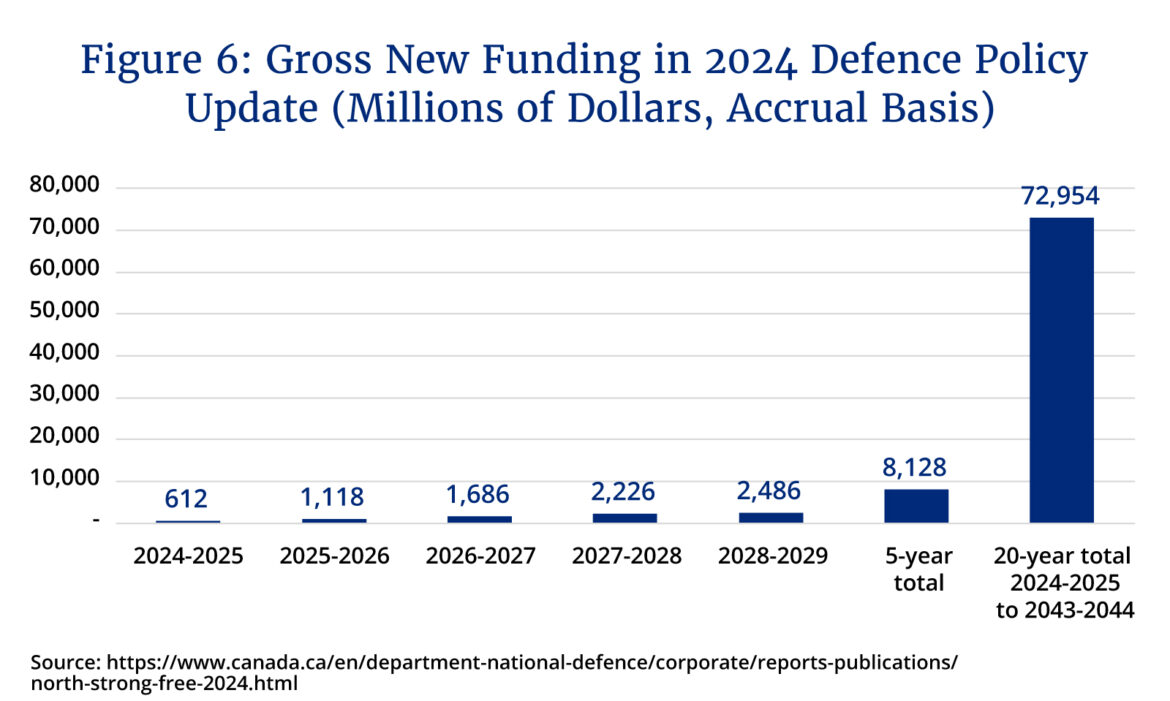

More specifically, it commits to investing $8.1 billion over the next five years and $73 billion over the next 20 years to Canadian defence. While several of the initiatives in the defence policy update are laudable, including efforts to increase recruitment and retention, as well as crucial investments in new equipment, a few things stand out.

First, the 1.76 percent of GDP figure is difficult to verify based on what is in the defence policy and the 2024 budget. For example, while the government provides a fact sheet attempting to explain the 1.76 percent figure, roughly 15 percent of Canadian defence spending in 2029-30 is expected to come from other government departments. Yet it’s unclear which departments and programs are accounted for in the calculation.

Shimooka has even written for The Hub that if one accounts for planned or underway projects and personnel additions, which are inexplicably excluded from the defence policy, then the government is likely to exceed the 2-percent target. Either way, the government would do well to be clearer and more transparent about how Canada is planning to get there by the decade’s end.

Second, most of the planned spending is in the out years, despite Defence Minister Bill Blair stating in early March that Canada’s armed forces are in “a death spiral” when it comes to recruitment. Only $612 million in incremental spending is earmarked for the 2024-25 fiscal year, with an additional $1.1 billion coming in the following year. The majority of the incremental $8.1 billion announced in the defence policy update is not expected to be spent for several years. In addition, of the nearly $73 billion that is to be spent on defence over the next 20 years, only 11 percent is planned to be spent in the next five years. Given the severe concerns about the diminished size of the CAF and its operational readiness raised above, the investments in this plan appear inadequate to make a significant difference in the near term.

Furthermore, there are also reasons to question whether the projected increases in defence spending will occur as planned, particularly when focusing on major equipment purchases. It’s one thing to earmark spending increases in government spending documents, but it’s another to ensure that there is adequate state capacity to turn those investments into the personnel and equipment that Canada’s armed forces desperately need.

A lot has been written on the reasons behind Canada’s successive defence procurement fiascos and failures to meet budget targets. These include a lack of accountability, partisan politics that intervenes to ensure defence spending results in partisan “wins,” problems with institutional design in the procurement system, misalignment between project costs and defence policy objectives, an opaque combination of cash and accrual budgeting, and bureaucratic politics that sees different departments and armed forces branches pitted against each other, often with misaligned incentives.

The situation has gotten so dire that a 2019 Senate report revealed that based on DNDs own analysis, procurement times had reached 16 and a half years by 2010-11, which was 66 percent greater than in 2004. Unfortunately, several recent reports from Canada’s auditor general give little reassurance that much has changed, finding that several recent initiatives were delayed, over budget, and not meeting timelines. With the state of the CAF and Canada’s international commitments in peril, long procurement times mean that the Canadian military will not have the personnel and equipment needed for the threats they face for decades to come. Despite Canada’s poor record in meeting its NATO commitments, the situation could get worse in the short term if planned investments are not realized in a timely manner.

Key takeaways

One of the barriers to addressing the challenges of low defence spending and personnel and equipment issues within the CAF is that, in the past, Canadian voters placed little political value on seeing these issues solved. Successive governments have responded to the lack of political incentives for change with ambivalence towards defence policy. However, the politics of defence policy may be changing. According to polling from Angus Reid in March 2024, a majority of Canadians (53 percent) favour either increasing defence spending to meet our NATO commitments or going beyond them. This compares to only 43 percent holding those views in November 2019. Likewise, 29 percent of Canadians feel that focusing on military preparedness and presence on the world stage should be our top foreign affairs priority, compared to only 12 percent in 2015.

As we highlighted above, it’s far from clear that Canada will meet its spending targets according to current plans, and the CAF is in dire need of new personnel and equipment. Despite new spending promises, the evidence suggests that Canada is still off track to meet its targets by the decade’s end, and in any case, there will also likely be several headwinds to actually delivering on its planned spending.

Given the shifting priorities among Canadian voters, it may be time for federal government to more seriously commit itself to meeting its international commitments and address the internal challenges that will stand in the way of realizing those goals.

This DeepDives essay was made possible thanks to the support of readers like you and the Centre for Civic Engagement.

Recommended for You

‘We love big spending’: Janet Brown and Dave Cournoyer on Alberta’s political paradox

‘The EV subsidies were a Faustian bargain’: Canada’s auto sector is in big trouble

Jared Kushner—the world’s most underrated diplomat?

Need to Know: The world is forgetting what happened on October 7th