As part of a paid partnership, this month The Hub will feature excerpts from this year’s five shortlisted books for the Donner Prize, awarded to the best public policy book in Canada. Our podcast Hub Dialogues will also feature interviews with the authors. The winning title will be awarded $60,000 by The Donner Canadian Foundation on May 8th.

The following is an excerpt from Pandemic Panic: How Canadian Government Responses to Covid 19 Changed Civil Liberties Forever (Optimum Publishing International, 2023).

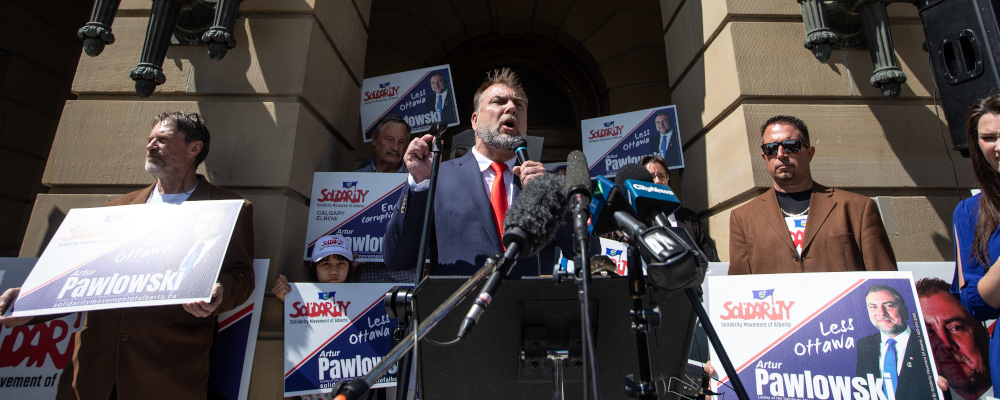

Artur Pawlowski is a pugilistic street pastor and the founder of Street Church Ministers based in Calgary. He has never exactly been a shrinking violet and has embraced some truly kooky views. Perhaps because of this, his conduct was countered with one of the most brazenly unconstitutional instances of a judge proscribing compelled speech in any Western democracy.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Pawlowski quickly became an outspoken critic of public health measures. As lockdowns and other public health measures dragged on, Pawlowski ramped up his incendiary actions. During Easter 2021, police visited his church following reports that it was flouting public health and social distancing orders. In a viral video, Pawlowski shouted at the police, “[g]et out! Get out immediately! Gestapo is not welcome here! Do not come back, you Nazi psychopaths! Detaining people at the church during the Passover!” On that occasion, police left, and no tickets were issued, but Pawlowski was arrested in May 2021 for organizing an in-person gathering during a brutal third wave of the virus.

In 2021, after being found in contempt of court, alongside his brother Dawid, for violating a court order “directed at mitigating the risk posed by the novel coronavirus (COVID-19).”

Shockingly, among the sanctions imposed on the two brothers by the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench was the condition that whenever either brother criticized Alberta Health Services orders or recommendations, they must recite the following disclaimer:

I am also aware that the views I am expressing to you on this occasion may not be views held by the majority of medical experts in Alberta. While I may disagree with them, I am obliged to inform you that the majority of medical experts favour social distancing, mask wearing, and avoiding large crowds to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Most medical experts also support participation in a vaccination program unless for a valid religious or medical reason you cannot be vaccinated. Vaccinations have been shown statistically to save lives and to reduce the severity of COVID-19 symptoms.

This unusual order quickly raised concerns about its validity under section 2 of the Charter, which protects freedom of thought, belief, opinion, and expression, including the right to be free from compelled speech. “I said, I will not obey this court order,’” Pawlowski told Fox News at the time, before the order was stayed upon appeal. “I refuse to obey a crooked judge’s order. He’s not a judge, he’s a political activist.”

Section 2 of the Charter guarantees Canadians the freedom to peacefully assemble, and to express themselves politically, and specifically protects the right to political dissent. The guarantee is content-neutral. Nonetheless, governments, and other government-sanctioned bodies such as regulators and administrators, implemented policies that had a chilling effect on free expression throughout the pandemic and directly restricted the right of Canadians to peacefully assemble to express their grievances with COVID-19 policies.

Freedom of expression and peaceful assembly are fundamentally important to the functioning of Canada’s liberal democracy. They guarantee that Canadians can peacefully organize and express themselves in matters relating to public policy. Without these rights, governments would be free to act unopposed, and their policies, including unjust policies, would be uncontested. Without healthy questioning of authority, we can never be sure that the government is doing what is in our best interests and whether the evidence for their positions is sound.

Political expression is considered core expression, and as such can only be restricted for the most substantial and pressing government objectives, unlike other forms of expression such as pornography and advertising, which are marginal to the goals that underlie protecting free expression.

There are at least three reasons why freedom of expression matters. First, it promotes truth-seeking: there can be no advancement of knowledge and testing of ideas without open discourse. Second, it is a condition necessary for the flourishing of democracy since there can be no political dissent and thus meaningful democracy without free expression. And third, free speech promotes individual autonomy since we develop as rational beings through unencumbered expression.

Compelled speech has attracted particular attention by constitutional scholars for a number of reasons. The exchange of information and functioning of discourse depends on the basic premise that expression reflects something authentic to the individual. Once that perception is broken by an apparatus of the state prescribing words that we must say, we become fundamentally cut off from an important source of truth. Moreover, compelling speech appears to run dangerously close to compelling thought. Philosopher Charles Taylor wrote that language gives form to our feelings and ideas and brings them “to fuller and clearer consciousness.”

The COVID-19 pandemic was the first in history that saw the conjunction of viral contagion and fast-moving social networks. Information spread even faster than a highly infectious virus, and even the most pro-free-speech countries resorted to measures that ordinarily they would reject as unconstitutional limitations on expression in a free society.

In selectively censoring narratives that were critical of the dominant government response to the virus, governments undermined their own appearance of partiality and potentially even reinforced scepticism about the authority of public health.

On the one hand, it’s clear that given the firehose of information that erupted early on in the pandemic, some streamlining of which facts could be relied upon and which could not was necessary. And the social media platforms are private companies, not governments. As civil libertarians, we tend to think that private companies, no matter how widespread their influence or how vital a role they play in society, ought to be able to make their own rules. Alternative social media platforms such as Rumble were available for those who did not wish to get their information on platforms that restricted content.

However, when a restriction on speech is ultimately backed by government coercion, as in the case of a judicial order forbidding individuals from protesting or even communicating about the possibility of protesting online, or of a regulatory college policing the social media content of its member physicians, it’s different from a private actor’s decision. You may have a right to delete your Facebook account if you don’t like the platform’s policy on posting about COVID-19, but you don’t have a right to ignore a judicial order or law. Thus, only restrictions on speech that are both demonstrably necessary and sufficiently tailored should be acceptable under the Charter, particularly when the speech in question is political and thus at the core of the guarantee of free expression.

Recommended for You

The Notebook by Theo Argitis: Carney’s One Big Beautiful Tax Cut, and fresh budget lessons from the U.K.

Christopher Snook: Is Canada sleepwalking into dystopia?

Rudyard Griffiths and Sean Speer: The fiscal hangover from the One Big Beautiful Bill hits Canada

‘A fiscal headache for Mark Carney’: The Roundtable on how Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill could affect Canada