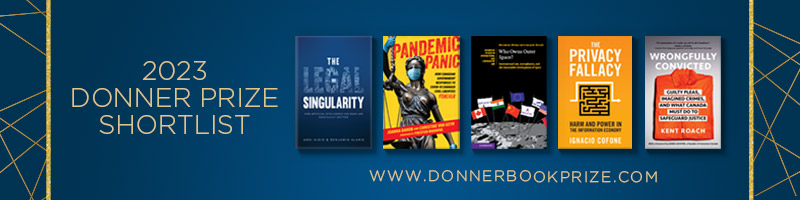

As part of a paid partnership, this month The Hub will feature excerpts from this year’s five shortlisted books for the Donner Prize, awarded to the best public policy book in Canada. Our podcast Hub Dialogues will also feature interviews with the authors. The winning title will be awarded $60,000 by The Donner Canadian Foundation on May 8th.

The following is an excerpt from Who Owns Outer Space? International Law, Astrophysics, and the Sustainable Development of Space (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

The asteroid 101955 Bennu is just a pile of rubble, weakly held together by its own gravity, the remnants of a catastrophic event that occurred a billion years ago. But Bennu is also a bearer of both life and death, containing clues about the origins of life on Earth while, at the same time, having the potential to destroy humanity. For over time, the agencies of physics and chance have brought the 500-metre-wide asteroid onto an orbit very near to Earth.

A robotic spacecraft named OSIRIS-REx set out in September 2016 to make contact with Bennu. After many rehearsals, flying close to Bennu each time, the spacecraft made a brief landing—a “touch-and-go” that enabled it to collect a sample from the asteroid’s surface. Scientists will spend decades analysing the 120 grams of material, which include amino acids, the building blocks of life.

The OSIRIS-REx mission, however, is about more than science. NASA readily admits that the visit to Bennu is a prelude for possible mining operations, with governments and private companies hoping to extract water from asteroids to make rocket fuel—thus enabling further space exploration and, perhaps, an off-Earth economy. But some states oppose these plans, arguing that space mining, were it to happen, would be illegal in the absence of a widely agreed multilateral regime. They point to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits “national appropriation” and declares the exploration and use of space to be “the province of all [hu]mankind.” There are also reasons to worry that space mining, if done without adequate oversight, could create risks—including the low probability, high-consequence risk of an asteroid being inadvertently redirected onto an Earth impact trajectory.

A little Pomeranian called Saba missed out on the chance to join Sharon and Mark Hagle on the first of their four planned flights to space, though Blue Origin did offer the dog a consolation prize—a specially fitted flight suit! As for the Hagles, they already have tickets for Virgin Galactic and are now in talks with SpaceX. Travelling to space is an “extraordinary” experience for the Florida-based couple, whose previous adventures included swimming with whales and abseiling into caves. “My thought is you go, I go,” Sharon said of her 73-year-old property developer husband. “Mark has always taken me out of my comfort zone.”

More and more of the world’s ultra-rich are travelling to space as tourists on short sub-orbital flights or much longer orbital flights, with increasing numbers going to the International Space Station. Trips around the Moon might also become a reality soon. Hollywood, unsatisfied with the visual effects provided by CGI or parabolic flights on aeroplanes, is right behind them, with Tom Cruise expected to fly to the International Space Station for a film shoot soon. It is all great fun, of course, unless one considers the environmental impacts.

The Soviet spy satellite Kosmos 1408, launched in 1982, ran out of propellant decades ago and became just another piece of Space junk…until it found a new purpose in life. It was chosen as a target for a powerful military to demonstrate a capability that everyone already knew it possessed—to destroy a satellite at will.

A ground-launched missile struck the 1,750 kg satellite at a relative speed of at least 20,000 kilometres per hour, creating a huge explosion and, at the same time, more than a thousand pieces of high-velocity space debris large enough to be tracked by ground-based radar. Tens of thousands of smaller but still potentially lethal pieces were also undoubtedly created, many of them on elliptical orbits that cross the orbits of thousands of operational satellites, as well as the International Space Station and China’s new Tiangong Space Station. Immediately after the explosion, astronauts, cosmonauts, and taikonauts retreated into the shelter of their capsules, which are hardened for atmospheric re-entry, and closed the hatches while the highest concentrations of debris flew by.

That was not the end of the story, however. Some of the debris will remain in orbit for many years, posing an ongoing threat to all satellites, including many operational satellites belonging to Russia itself, the state that took this dangerous and completely unnecessary action.

SpaceX recently moved the bulk of its operations from California to Texas, attracted by the Lone Star State’s low taxes and minimal regulations. The move may also have contained an implicit threat to the U.S. government: the now-dominant space actor could up stakes again, but next time to another country. Luxembourg, a well-established tax haven, would be an obvious place to incorporate. Although a tiny European country, it provides a friendly home for two of the world’s largest operators of communications satellites in geosynchronous Earth orbit (GEO), and, in 2017, adopted legislation to facilitate commercial space mining. SpaceX, meanwhile, has already acquired two large oil-drilling platforms that could be used to allow launches, quite literally, offshore.

Having launched more than 5,000 satellites since 2019, SpaceX now controls large swaths of Earth’s most desirable orbits. Should one company, or indeed any actor, be allowed to use the most valuable parts of low Earth orbit (LEO) to such an extent that its use effectively excludes other actors from operating there safely? At what point does SpaceX exceed the carrying capacity of LEO and degrade spaceflight safety for everyone?

Tighter regulations are coming. But those regulations will be the result of negotiations, and companies, knowing this, are now working to establish the strongest possible negotiating positions. The emergence of Luxembourg and other “flag-of-convenience” states in the space domain will certainly help those who seek to minimise regulation. SpaceX only exists because of NASA contracts provided to it when it was a fragile start-up. It still relies on NASA and U.S. Space Force contracts for revenue, but the company is growing ever more powerful, launching thousands of satellites each year and planning missions to both the Moon and Mars. At some point, governments may find that they are negotiating with a leviathan that is both able and willing to transcend all boundaries.

Recommended for You

The Notebook by Theo Argitis: Mark Carney’s first major tests

‘There can be massive policy investments made in AI literacy’: Five takeaways from John Stackhouse, Janice Gross Stein, and Jaxson Khan on the race for AI adoption in Canada

Michael Geist: Children accessing porn is a problem, but government-approved age verification technologies are not the answer

Daniel Zekveld: Age verification for pornography is not government overreach